Introduction

The human gut microbiome, a highly complex system of trillions of microbes, plays a critical role in overall wellness. Although diet and genetics are established in influencing gut microbial composition, recent studies identify travel and geographical locations as significant determinants. As individuals travel across diverse environments there is a dynamic shift in their gut microbiota reflecting the variety of microbial exposures they have encountered.

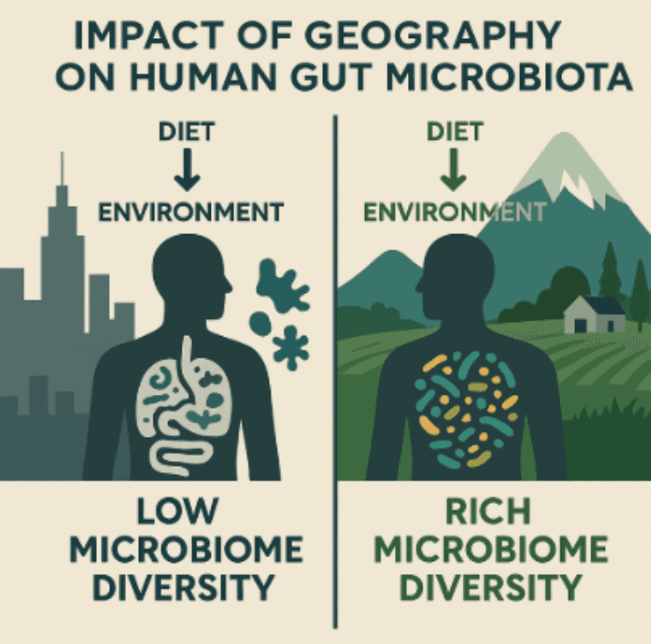

Geographic Influence on Gut Microbiota Composition

The geographical position has a major impact on the structure and diversity of the human gut microbiota. The investigations have revealed that the populations from distinct regions have characteristic microbial communities influenced by dietary habits, lifestyle, and environmental exposures.

For example, a detailed investigation of 651 individuals throughout the urban and rural areas of Kazakhstan demonstrated marked differences in microbial composition associated with urbanization. Urban residents showed lower alpha diversity, an elevated Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio, and reduced levels of genera such as Coprococcus and Parasutterella, along with higher abundances of Lachnospiraceae and Dorea formicigenerans. In contrast, rural inhabitants exhibited greater microbial richness and increased presence of Ligilactobacillus, Sutterella, Paraprevotella, and Klebsiella ,bacteria commonly associated with high-fibre, plant-based diets. These microbial differences were accompanied by notable dietary patterns, with urban participants consuming more processed and high-fat foods, while rural individuals favoured whole grains, vegetables, and fermented dairy products, which are known to support greater microbial diversity. Another interesting finding of this study is that the urban population had a slightly higher antibiotic-resistance and virulence genes which were associated with the higher population density and easier accessibility to hospitals and medications. On the contrary, the rural population harboured genes associated with toxicity and other mobile genetic elements associated with agricultural practices, livestock exposure and poor sanitation.

In a similar study, researchers compared healthy Indian adults from a high-altitude rural region (Leh, Ladakh) with those from a lowland urban area (Ballabhgarh), focusing on the relative abundances of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria. The rural high-altitude group showed higher levels of Bacteroidetes, lower levels of Proteobacteria, and greater overall microbial diversity. Additionally, Prevotella, Megasphaera, and Bacteroides faecis were more prevalent in the rural samples compared to their urban counterparts. These studies suggest that geography along with the traditional diets, and environmental exposures, does play an important role in determining the gut microbial composition .

Impact of International Travel on Gut Microbiota

A longitudinal study collected 718 stool samples from 159 international students before their travel to Cusco, Peru, during their stay, and after their return, tracking changes in student's gut microbiota over time. While overall gut microbial diversity (alpha diversity) remained relatively stable, substantial shifts in microbial composition were observed during travel However, students who developed diarrhoea showed a loss of overall stability and increase in diarrheagenic E. coli isolates containing antimicrobial-resistance genes (ARGs) which persisted for weeks post recovery.

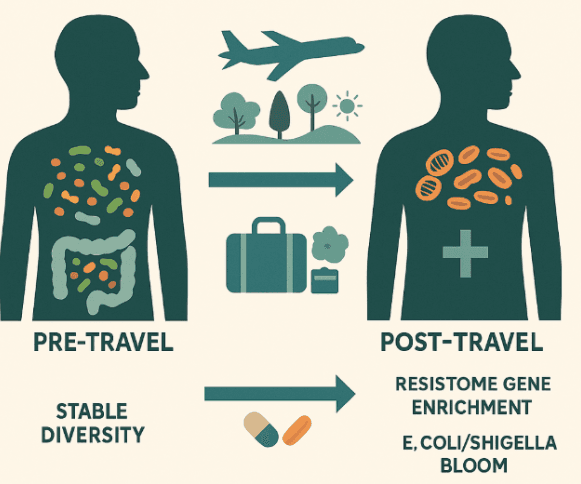

Similarly, another study showed that international travellers visiting low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) displayed significant shifts in their gut microbiota. The authors found essentially no change in microbial richness or alpha diversity, but observed approximately 40-fold increase in relative abundance of Escherichia/Shigella, with 89% of travellers testing positive for diarrheagenic E. coli (DEC) upon return. Notably travellers who had higher abundance of Ruminococcaceae and Coprococcus before travel acquired DEC pathotypes, while Anaerostipes spp was associated with a reduced risk of DEC pathotype colonization.

These studies together indicate that international travel appears to influence gut microbial composition, particularly through transient increases in certain bacterial groups such as diarrheagenic E. coli. While overall microbial diversity tends to remain stable, individual responses may vary, with some patterns in pre-travel microbiota potentially shaping susceptibility to specific strains. These findings contribute to a growing understanding of how travel intersects with gut health and highlight the subtle, individualized nature of microbiome changes across different environments.

Fig 02: A flat-style infographic illustrating how international travel affects the gut microbiota, showing shifts from stable diversity pre-travel to increased resistome gene enrichment and E. coli/Shigella presence post-travel.

Ethnicity and Its Role in Gut Microbiota Variation

Ethnicity, which is combined with cultural dietary patterns and eating habits also affects the gut microbiota structure. A study among a multi-ethnic Malaysian population identified that ethnicity had a significant effect on gut microbiota patterns even among the people living within the same geographical area. This indicated that the cultural food choices and lifestyle habits peculiar to diverse ethnic populations influence microbial diversity.

Strategies to support gut microbiota during travel

Dietary Choices: Consume a variety of fibre-containing foods to promote healthy microbes.

Probiotics: Consider probiotic supplements to maintain microbial balance.

Hydration & Sanitation: Drink safe water and maintain good hygiene to avoid contact with harmful pathogens.

Wise Antibiotic Use: Consume antibiotics only when prescribed by the physicians as they can disrupt gut microbial equilibrium.

Conclusion

The geographical and travel factors have great impacts on the human gut microbiome, reflecting the dynamic interaction between our environment and internal microbial ecosystems. Research indicates that even brief travel can affect the microbial balance, with long-term geographical variation imparting lasting impressions. Understanding these influences can guide strategies to protect and sustain gut health amid changing environmental and lifestyle conditions.

-Shravya B U

References

Boolchandani, M., Blake, K. S., Tilley, D. H., Cabada, M. M., Schwartz, D. J., Patel, S., ... & Dantas, G. (2022). Impact of international travel and diarrhea on gut microbiome and resistome dynamics. Nature communications, 13(1), 7485.

Das, B., Ghosh, T. S., Kedia, S., Rampal, R., Saxena, S., Bag, S., ... & Ahuja, V. (2018). Analysis of the gut microbiome of rural and urban healthy Indians living in sea level and high altitude areas. Scientific reports, 8(1), 10104.

Dwiyanto, J., Hussain, M. H., Reidpath, D., Ong, K. S., Qasim, A., Lee, S. W. H., ... & Rahman, S. (2021). Ethnicity influences the gut microbiota of individuals sharing a geographical location: a cross-sectional study from a middle-income country. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 2618.

Mlangeni, T., Jian, C., Häkkinen, H. K., de Vos, W. M., Salonen, A., & Kantele, A. (2025). Travel to the tropics: Impact on gut microbiota. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 102869.

Smits, S. A., Leach, J., Sonnenburg, E. D., Gonzalez, C. G., Lichtman, J. S., Reid, G., ... & Sonnenburg, J. L. (2017). Seasonal cycling in the gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. Science, 357(6353), 802-806.

Vinogradova, E., Mukhanbetzhanov, N., Nurgaziyev, M., Jarmukhanov, Z., Aipova, R., Sailybayeva, A., ... & Kushugulova, A. (2024). Impact of urbanization on gut microbiome mosaics across geographic and dietary contexts. Msystems, 9(10), e00585-24.