History

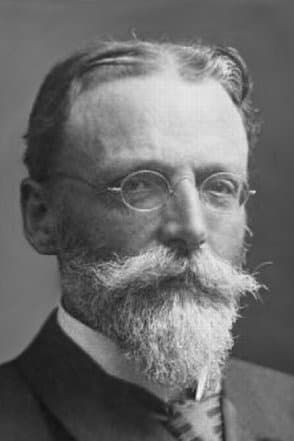

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is one of the most popular, versatile, and well-studied bacteria on the planet. It is ubiquitous in nature, and different strains of E. coli are responsible for both health and disease. Beyond its role in human health, non-pathogenic strains of E. coli are widely used as model organisms in research. Researchers and students in the life sciences, at least once in their academic journey, have been best friends with E. coli, as it can be conveniently grown and handled in the laboratory. We owe the discovery of this bacterium to the German microbiologist and pediatrician Theodor Escherich.

In 1884, while studying the role of infant gut microbes in digestion and disease, Escherich discovered a fast-growing bacterium and named it Bacterium coli commune. Later, in 1988, it was renamed as Escherichia coli in his honor.

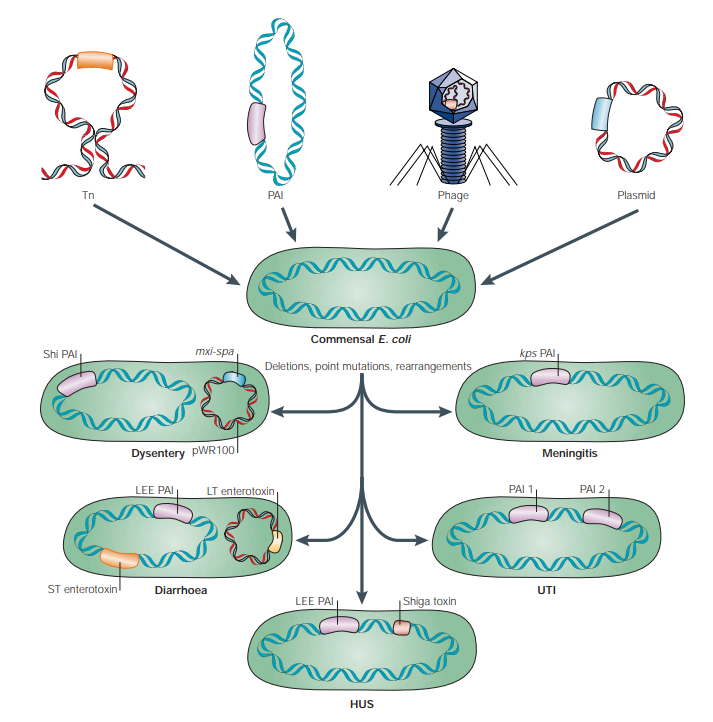

Few strains of E. coli are beneficial to human health, while others can cause serious infections. An important question is how such friendly, non-pathogenic bacteria become pathogenic foes. E. coli’s ability to adapt to diverse niches and its remarkable versatility act as a double-edged sword. While these adaptive capabilities allow E. coli to survive in a wide range of environments, they can also pose a significant risk to human health. By acquiring new genetic material from its environment or from other bacteria and viruses, E. coli can transform from a harmless commensal into a pathogenic organism-making it harmful and, at times, truly dangerous to humans.

Theodor Escherich

Pathogenesis

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is not inherently pathogenic, as it is a part of the normal gut microflora and exists as a commensal organism. However, depending on the type and combination of foreign DNA it acquires, different strains of E. coli can become pathogenic. These pathogenic strains differ in their mechanisms of infection, the toxins they produce, and the types of infections they cause, resulting in a wide range of clinical symptoms.

E. coli can cause both intestinal infections and extraintestinal infections (infections occurring outside the intestine).

Intestinal Infections

Intestinal infections are caused by five major pathotypes of E. coli:

Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC):

EIEC is genetically, biochemically, and pathologically similar to Shigella species. It occasionally causes dysentery and inflammatory colitis, but more commonly results in diarrhoea. The virulence factors of EIEC are encoded on acquired plasmids, such as the mxi and spa genes, which encode components of the secretion system and proteins required to deliver toxins into host cells.

Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC):

A specific region of DNA known as the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) is responsible for the unique mechanism by which EPEC infects host epithelial cells. This process, called “attaching and effacing,” involves the bacterium attaching to epithelial cells, destroying microvilli, and altering cell structure. As a result, intestinal inflammation, increased intestinal permeability, and active ion secretion occur, ultimately leading to watery diarrhoea.

Enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) / Shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC):

This strain carries genes that encode Shiga toxin along with LEE. When Shiga toxin enters the bloodstream, it can damage kidneys and lead to hemolytic uremic syndrome. Within the intestine, it damages colonic cells, resulting in intestinal perforation, necrosis, haemorrhagic colitis, and bloody diarrhoea.

Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC):

ETEC is a common cause of travellers’ diarrhoea. It harbours genes that encode enterotoxins, which are of two main types: heat-labile toxin (LT) and heat-stable toxin (ST). A strain may produce either one or both toxins. The LT toxin resembles cholera toxin and increases chloride ion secretion while inhibiting absorption, leading to diarrhoea. ST toxins consist of two unrelated classes, STa and STb. STa is associated with human disease and contributes to increased ion secretion, resulting in diarrhoea.

Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC):

EAEC adheres to epithelial cells in the colon and secretes toxins. Both pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains exhibit a characteristic “stacked-brick” pattern of aggregation and adherence, which gives this pathotype its name. Multiple virulence factors may be produced by EAEC, making it difficult to identify a single toxin responsible for pathogenicity. Recent studies suggest that the transcriptional activator AggR regulates the expression of several virulence factors, proteins, and toxins involved in diarrhoea, and therefore can be used as a marker for identifying pathogenic EAEC strains.

Mobile genetic elements—including plasmids, transposons, bacteriophages, and pathogenicity islands—drive the evolution of pathogenic E. coli by introducing, deleting, or rearranging virulence genes, giving rise to strains that cause diarrhoea, dysentery, haemolytic uremic syndrome, urinary tract infections, and meningitis.

Extraintestinal Infections

Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC):

Uropathogenic E. coli is responsible for urinary tract infections and harbours a variety of virulence genes that aid in the successful infection of urethra and kidneys. These strains most likely first colonise the gut and then translocate to the periurethral region. Alternatively, infection can be acquired in hospital settings through the insertion of urinary catheters, where the bacteria ascend the urethra and establish themselves in the urinary tract. UPEC produces several virulence factors, such as adhesins and toxins, which cause inflammation and damage to renal epithelial cells.

Meningitis- and sepsis-associated E. coli (MNEC):

When a pathogenic strain of E. coli enters the bloodstream, it can cause bacteraemia and may eventually lead to meningitis or sepsis. MNEC strains possess specific genes encoding virulence factors that enable them to cross the blood–brain barrier and bind to brain endothelial cells. These genes are typically absent in non-pathogenic strains of E. coli.

Transmission

Ingestion of foods such as undercooked meat and raw vegetables contaminated with pathogenic strains of E. coli can lead to infection. E. coli infections can also be acquired in hospital settings through the use of unsterilised catheters, ventilators, and other medical devices.

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of E. coli infection usually begin within 16 hours of ingesting contaminated food. Clinical manifestations vary depending on the pathogenic strain involved. Intestinal infections may cause watery diarrhoea or dysentery, often accompanied by fever and abdominal cramps. A burning sensation or pain during urination, along with an increased urge to urinate, is commonly associated with urinary tract infections.

Diagnosis

In cases of severe or prolonged symptoms, stool tests are performed to identify the causative organism. Currently, PCR-based assays are widely used for diagnosis and are considered reliable. Previously, stool culture followed by specific biochemical tests was used to identify particular strains of E. coli based on their metabolic characteristics.

Treatment

For mild E. coli infections, anti-diarrhoeal medications and rehydration therapy are recommended as the first line of treatment. Antibiotics are generally avoided, as E. coli can rapidly develop antibiotic resistance, which may have serious consequences for patient health.

In cases of severe diarrhoeal illness requiring hospitalisation, antibiotics such as rifaximin, azithromycin, or ciprofloxacin may be recommended. However, antibiotic therapy is only prescribed for certain pathogenic strains. For example, antibiotics are not recommended for infections caused by EHEC/STEC, especially in children and the elderly, due to the increased risk of developing hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Prevention

E. coli infections can be prevented by thoroughly cooking meat, washing fruits and vegetables with purified water, and practising regular hand hygiene. In immunocompromised individuals who are at higher risk of infection, prophylactic antibiotics such as rifaximin or bismuth subsalicylate may be considered, but only when prescribed by a physician. Regular sterilisation of medical devices and strict adherence to hygiene protocols in hospitals can further reduce the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia and catheter-associated urinary tract infections.

Microbe profile

Shape: Rod shaped/Bacilli

Gram nature: Gram -ve

Spore formation: No

Biofilm formation: yes

Oxygen requirement: facultative anaerobe

Optimal temperature: 37°C

Optimal pH: wide range of pH(2 -10)

Nutrient usage/Laboratory culture media: McConkey, Eosin Methylene Blue (EMB) Agar

Taxonomic classification

Domain: Bacteria

Kingdom: Pseudomonadati

Phylum: Pseudomonadota

Class: Gammaproteobacteria

Order: Enterobacterales

Family: Enterobacteriaceae

Genus: Escherichia

Species: Escherichia coli

-Khushi.C

Also Read: The MicroByte Pathogen Series : Vibrio cholerae- The Causative Agent of Cholera

References

Mueller, M., Rausch-Phung, E. A., & Tainter, C. R. (2025, December 14). Escherichia coli Infection. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564298/

Kaper, J. B., Nataro, J. P., & Mobley, H. L. T. (2004). Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2(2), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro818