History

Vibrio cholerae is a bacterium of the genus Vibrio, which derives its name from ‘vibrare’, Latin for rapid motion or vibration. The species designator ‘cholerae’ refers to the disease it is famously known to cause, cholera. Cholera is an ancient affliction, and the name is thought to have come from the Greeks, with ‘chole’ meaning bile, and ‘rein’ meaning flow. Another, grosser hypothesis, has to do with the fact that the word ‘cholera’ also meant ‘gutter’- leading scholars to theorise that the expulsion of fluids from one affected evoked the imagery of an overflowing drainage system. Yet another possibility is that the word was derived from an obsolete Attic Greek word ‘cholās’, meaning intestine, in relation to the system mainly affected. The precise origin is still unknown, but cholera as an illness has reached a status of infamy due to havoc it has wreaked on civilisation, and the burden on global health it still exerts.

As seen in a coloured light micrograph

The earliest reference to a cholera-like condition comes from 5th century BC, Gujarat, India, in the form of a temple inscription, describing a condition that emaciated brave men, and terrible enough to be a divine curse. However it is uncertain whether it was cholera that was being described. The earliest confirmed record of cholera also comes from India, in 1503, soon after Vasco da Gama’s arrival, where the Calicut army described a disease of the stomach that struck suddenly, and claimed the lives of 20,000. Cholera has also caused multiple pandemics in human history, the first known of which also began in India, in the Gangetic Delta, in 1817. In five years, it spread through several Asian countries like Japan, China, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines, and by its end in 1824 it also arrived in West Asia and Europe. The third recorded cholera pandemic is noted to be particularly devastating, starting in India and affecting multiple continents, and yet was the one in which important developments in understanding this illness were made.

In 1854, John Snow laid the foundations for modern epidemiology by demonstrating that a single water source was responsible for the cholera spread raging through London, and by removing a pump handle on this fated Broad Street supply, succeeded in stopping the outbreak. Parallelly, Filippo Pacini, an Italian researcher, identified and cultivated the causative germ of cholera, naming it Vibrio cholerae, and proposed that the caused gastrointestinal damage lead to the observed symptoms, but was overshadowed by Robert Koch’s work on the same, despite being the original discoverer. Sadly, his credit was delivered posthumously. It was only later in 1884 that a pure culture was grown by Koch, and in the next year, a vaccine was made by bacteriologist Jaime Ferran y Clua.

The first six cholera pandemics are known to be caused by the ‘classical biotype’ of serogroup O1, and infections that followed were known also to be caused by other forms of this microbe- another biotype of O1 known as El Tor (based on the city it was isolated in), another serogroup, O139, and some ‘atypical’ variants of El Tor (serogroups are classified based on outer membrane composition differences) . An important modern outbreak of cholera took place in Haiti in 2010, where earthquake relief forces brought in the disease, and local healthcare systems couldn’t effectively keep up with another crisis, leading to widespread mortality and infections.

From the 1900s, developments in modern science enabled a continually growing understanding of cholera and its causative agent. The mechanisms through which V. cholerae causes disease were identified, oral rehydration as a therapeutic route was developed, and its marine sources and associations were established. Notably, the latter information was discovered and used by Rita Colwell to develop low-cost filtration methods to reduce cholera in Bangladesh. These contributions spanned over microbiology, ecology, and biochemistry, and allowed for enhanced outcomes and prevention of this dreadful illness. Today, serogroups O1 and O139 remain the main V. cholerae forms of concern for causing disease, and cholera still causes millions of infections and tens of thousands of deaths every year, though it no longer remains a divine mystery.

A replica of the (handle-less!) Broad Street pump that John Snow identified as the infection reservoir for London’s 1854 cholera outbreak. The pink stone marks its original location.

Disease Caused & Symptoms

Vibrio cholerae, as discussed, causes cholera, which is typically associated with copious amounts of diarrhea and vomiting. Infection starts when pathogenic strains transit through the gastrointestinal tract and colonise the epithelia of the small intestine. Here, it secretes the cholera toxin, which is taken into the epithelial cells, where it is able to lower chloride and sodium absorption, and triggers the augmented release of water and chloride from the intestine, leading to large amounts of characteristic watery diarrhea. In severe infections, patients may enter hypovolemic shock due to excessive fluid loss, which is associated with high mortality; treatment must be administered in a timely manner.

Transmission

Cholera spreads through the fecal-oral route, where the infection can be transmitted through food and water that are contaminated with V. cholerae, or contact with individuals who are infected. V. cholerae can also be found in feces-contaminated marine environments, being tolerant of salt.

Diagnosis

Confirmation of a cholera case is done by isolating the microbe from stool culture, followed by serotyping for the known pathogenic serogroups O1 and O139. Sensitive methods like PCR are also gathering acceptance. The CDC also recommends starting treatment before a confirmation in case severe symptoms are present.

Treatment

The keystone of cholera treatment is effective rehydration. Based on an assessment of the level of fluid lost, and the patient’s condition, the appropriate rehydration method (oral/ intravenous/ both) must be chosen and administered urgently. Antibiotics are also given after initial dehydration is controlled, reducing duration and severity of symptoms, and excretion of infective bacteria.

Prevention

Since cholera is spread through infected water and food, ‘WaSH’ measures- water, sanitation, and hygiene are paramount for the prevention and effective control of the spread of cholera and similarly transmitted infections. Some measures that fall under WaSH strategies are behavioural such as handwashing and drinking water chlorination measures; some are infrastructural such as provision of safe potable water, handwashing areas, installation of water purifiers, and others are organisational, like sanitation legislation for food handling, and disease surveillance programs. Vaccination is another arm of cholera control, and helps in reducing cases in an outbreak, but challenges still exist such as regulatory differences between countries, logistics, and coverage rates. Research is ongoing to develop new vaccines, and improve immunization in vulnerable parts of the population like children and pregnant women.

Microbe Profile

Gram status: -ve

Shape: Comma-shaped bacillus

Spore formation: No

Motile: Motile through polar flagellum

Oxygen requirements: Facultative anaerobe / aerobe

Optimum temperature: 23–30°C

Optimum pH: around 8

Taxonomic Classification

Domain: Bacteria

Kingdom: Pseudomonadati

Phylum: Pseudomonadota

Class: Gammaproteobacteria

Order: Vibrionales

Family: Vibrionaceae

Genus: Vibrio

Species: Vibrio cholerae

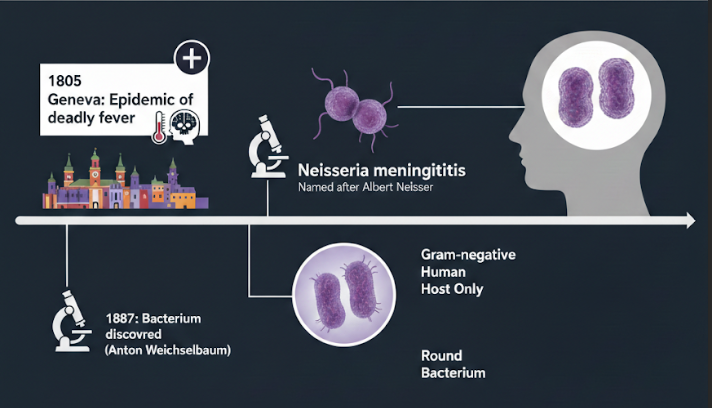

Also Read: The MicroByte Pathogen Series : Neisseria Meningitidis- Inside the Brain-Invading Bacterium

-Antara Arvind

References

Cholera Clinical Detection. (2024, August 13). Cholera. https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/php/laboratories/cholera-clinical-detection.html

Chowdhury, F., Ross, A. G., Islam, M. T., McMillan, N. a. J., & Qadri, F. (2022). Diagnosis, management, and future control of cholera. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 35(3), e0021121. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00211-21

Doni, L., Taviani, E., Bosi, E., Pruzzo, C., Martinez-Urtaza, J., & Vezzulli, L. (2025). Milestones in Vibrio Science and their Contributions to Microbiology and Global Health. Annals of Global Health, 91(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.4711

Gherlan, G. S., Lazar, D. S., & Florescu, S. A. (2025). Non-toxigenic Vibrio cholerae – just another cause of vibriosis or a potential new pandemic? Archive of Clinical Cases, 12(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.22551/2025.46.1201.10305

Kojima, S., Yamamoto, K., Kawagishi, I., & Homma, M. (1999). The Polar Flagellar Motor of Vibrio cholerae Is Driven by an Na + Motive Force. Journal of Bacteriology, 181(6), 1927–1930. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.181.6.1927-1930.1999

Kousoulis, A. A. (2012). Etymology of Cholera. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 18(3), 540. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1803.111636

Rodriguez, J. a. O., Hashmi, M. F., & Kahwaji, C. I. (2024a, May 1). Vibrio cholerae Infection. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526099/

Sheikh, H. I., Najiah, M., Fadhlina, A., Laith, A. A., Nor, M. M., Jalal, K. C. A., & Kasan, N. A. (2022). Temperature Upshift Mostly but not Always Enhances the Growth of Vibrio Species: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.959830

Tulchinsky, T. H. (2018). John Snow, Cholera, The Broad Street Pump; Waterborne diseases then and now. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 77–99). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-804571-8.00017-2

Nhu, N. T. Q., Wang, H. J., & Dufour, Y. S. (2019). Acidic pH reduces Vibrio cholerae motility in mucus by weakening flagellar motor torque. Pre-print. https://doi.org/10.1101/871475