Holobiome: Research I Articles I Updates I News I Series I Feed

Holobiome is a blog series that offers an AI-assisted summary of the latest research articles on human microbiome.

When Diet Feeds the Drug: How Gut Microbes Boost Metformin’s Power

This study looks at what happens when metformin, a common drug used to lower blood sugar, is paired with a diet containing a moderate amount of fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) in people with prediabetes and the gut microbiome turns out to be a key player. FODMAPs are the types of carbohydrates that escape digestion and become food for gut bacteria. When participants followed a moderate-FODMAP diet alongside metformin, their post-meal blood sugar levels dropped more than with a low-FODMAP diet, even though total calories, fiber, and macronutrients were carefully matched. From a microbiome perspective, this suggests that it wasn’t just the drug or the diet alone, but how the diet fed specific microbes that shaped the metabolic response.

Several bacterial species shifted in ways that help explain these benefits. The moderate-FODMAP plus metformin combination increased bacteria such as Butyricimonas virosa and Odoribacter splanchnicus, which are known producers of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), especially butyrate. These microbial metabolites are not just fuel for gut cells; they also act as signaling molecules that stimulate gut hormones like GLP-1, which boosts insulin release after meals. Indeed, people on the moderate-FODMAP diet showed higher GLP-1 levels and stronger late-phase insulin responses, aligning well with the rise in SCFA-producing microbes. At the same time, markers of low-grade inflammation were lower, supporting the idea that microbial by-products were calming metabolic inflammation while improving glucose control.

The study also highlights that not all microbiomes respond the same way to metformin. Participants who experienced more digestive side effects had higher baseline levels of Dorea formicigenerans, a bacterium linked to gut irritation and inflammation. This suggests that gut microbial profiles could one day help predict who will tolerate metformin and who might struggle with side effects. Overall, the findings paint a clear picture: feeding the right microbes can amplify the benefits of medication. Rather than viewing diet and drugs as separate tools, this work shows how shaping the gut ecosystem can make standard treatments work better and more comfortably for people at risk of developing diabetes.

How Sweeteners Reshape the Gut Microbiome During Weight Loss

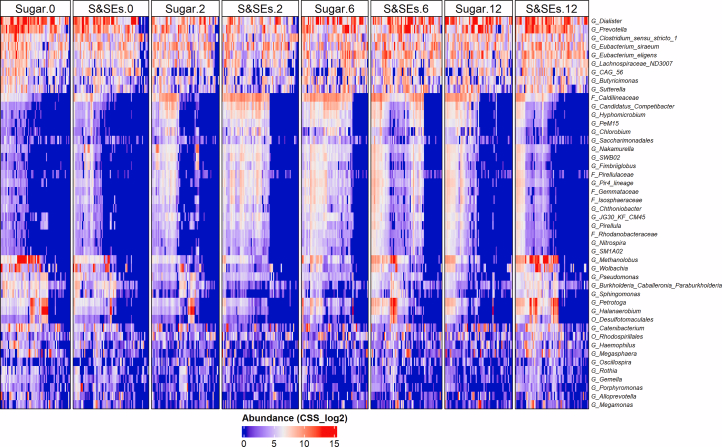

In our gut lives a bustling ecosystem of bacteria that respond quickly to what we eat, producing metabolites that influence digestion, appetite, and metabolic health. This long-term randomized study explored how replacing sugar with S&SE (sweeteners and sweetness enhancers) in a healthy, reduced-sugar diet shaped the gut microbiome of adults with overweight or obesity. After an initial weight-loss phase, participants followed either a sugar-rich diet or a diet where sugars were largely replaced by S&SE for one year. Rather than focusing only on body weight, the researchers tracked how microbial communities changed over time, recognizing that these microbes may help explain why some diets support longer-term metabolic benefits.

The gut microbiome responded differently depending on the type of sweet taste exposure. People consuming S&SE showed shifts toward bacterial groups associated with short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, including pathways linked to butyrate and propionate generation. These SCFAs are well known for strengthening the gut barrier, reducing low-grade inflammation, and stimulating gut hormones involved in appetite and glucose control. At the same time, microbes involved in methane-associated fermentation pathways increased, suggesting changes in how carbohydrates were processed in the colon. Together, these shifts point to a microbial environment that may favor improved metabolic signaling rather than excess energy storage.

What is especially notable is that these microbial changes occurred without worsening blood lipids, insulin sensitivity, or inflammatory markers, suggesting that long-term use of S&SE within a balanced diet does not harm cardiometabolic health. Instead, the microbiome appeared to adapt in ways that could support sustained weight management, possibly by influencing satiety hormones and energy extraction from food. This reinforces the idea that sweet taste alone is not the whole story what matters is how different nutrients feed different microbial networks.

Overall, the study highlights the gut microbiome as a critical mediator between dietary choices and metabolic outcomes. Replacing sugar with S&SE (sweeteners and sweetness enhancers) did more than cut calories; it reshaped microbial pathways tied to fermentation, inflammation, and hormone signaling. For people aiming to manage weight without giving up sweetness, the findings suggest that the gut ecosystem may quietly help translate those dietary swaps into lasting metabolic effects.

Heat map of microbial genera (rows) CSS normalized and log2 transformed abundance per sample with significant different abundance trends over time between the intervention groups.

Can Gut Bacteria Protect the Aging Brain After Surgery?

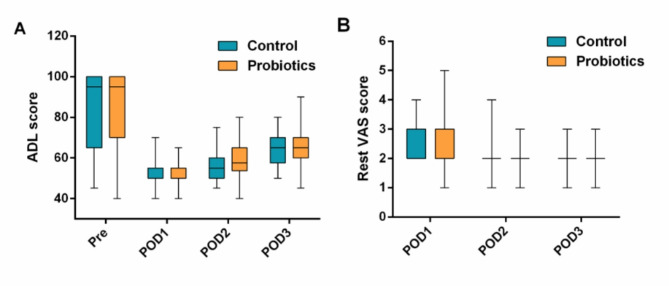

When we think about recovery after surgery, most of us picture physical healing and pain management but the trillions of bacteria living in our gut might also be quietly influencing how well the body and mind bounce back. This study explored whether giving elderly surgical patients a course of probiotics a supplement of beneficial bacteria around the time of their operation could protect against postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), a decline in memory and thinking that can follow anesthesia and surgery. The findings suggest microbes are more than passive passengers; they may actively shape inflammatory and neural responses after stress.

Participants who received probiotics containing well-studied gut symbionts like Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Enterococcus faecalis experienced lower rates of cognitive decline compared with those on a placebo. Beyond the cognitive tests, researchers measured shifts in inflammatory markers and gut microbial profiles. The probiotic group showed reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6 and increased levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) shortly after surgery molecular signals tied to both immune activity and brain health.

From a microbiome perspective, this intervention likely helped stabilize or rebalance bacterial communities that can be disrupted by surgical stress, antibiotics, and altered diet. While the paper did not catalog every species change, it points to a broader concept: gut microbes and their metabolic by-products can modulate systemic inflammation and interact with the gut–brain axis, the communication highway linking intestinal ecosystems to nervous system function. Healthy microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, for instance, are known to dampen inflammation and support neuronal signaling, and probiotic supplementation may help preserve their production when it otherwise falters around surgery.

Rather than being an afterthought, the gut microbiome emerges here as a potential ally for cognitive resilience. By helping to curb inflammation and support beneficial microbial activity during the perioperative period, specific probiotic strains might ease the mental fog that shadows many surgical recoveries. These findings underscore how nurturing the gut ecosystem even for just a few days could influence outcomes far beyond digestion, reaching into the brain and immune system in meaningful ways.

Perioperative changes in ADL and rest VAS scores. The line represents the median, boxes represent the IQR, whiskers represent the range. ADL: activities of daily living, VAS: visual analogue scale. IQR: interquartile range

The Battle on the Skin: Friendly Microbes vs. Staphylococcus aureus

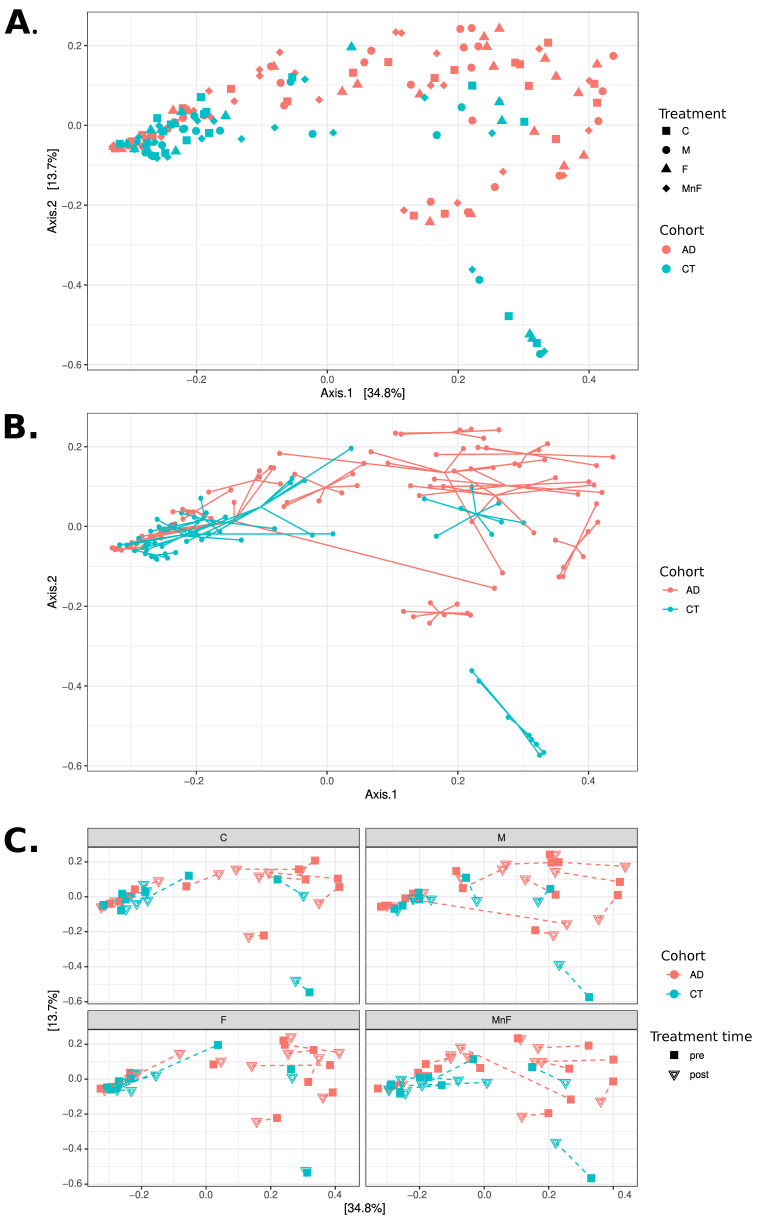

Our skin isn’t just a static barrier; it’s a vibrant ecosystem teeming with microbes that help protect us from pathogens and educate our immune system. In conditions like atopic dermatitis (AD) a chronic inflammatory skin disease marked by redness, itching, and barrier disruption this microbial community goes awry, a state scientists call dysbiosis. The study examined how the skin microbiome shifts in people with AD and whether those changes are stable or recover over time with treatment and improved skin health.

Healthy skin harbors a balanced mix of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms. In AD, this balance tilts: commensal species that normally help keep opportunistic microbes in check decline, while Staphylococcus aureus and related strains often flourish. This overrepresentation of S. aureus correlates with increased inflammation and flare severity, illustrating how microbial imbalance isn’t just a bystander but may actively contribute to disease mechanisms. Encouragingly, when the skin barrier is restored with proper therapy, many of these microbial shifts begin to reverse, suggesting that the skin microbiome can bounce back toward a healthier state.

From a microbiome perspective, these dynamics highlight the interplay between our immune system, skin environment, and resident microbes. A resilient microbiome helps fend off pathogens and modulates inflammation, whereas dysbiosis amplifies immune irritation and barrier breakdown. The research underscores that restoring microbial balance not just suppressing inflammation might be key to durable relief for AD sufferers. This work opens the door to microbiome-targeted therapies, including probiotics, prebiotics, and lifestyle factors that nurture beneficial skin microbes. Ultimately, the study reinforces a growing theme in microbiome science: healthy ecosystems matter everywhere microbes live, from the gut to the skin surface.

PCoA analyses at the species level using Bray–Curtis distances. All three panels display PCoA plots of the same samples in the same coordinate system. (A) Samples coloured by cohort, with shape indicating treatment (C, M, F, MnF). Note how the CT cohort appears mostly concentrated to the left, while the AD cohort is mostly located in the upper right of the figure. (B) Samples coloured by cohort, with samples belonging to the same individual connected with lines. Note how individuals appear to have mostly distinct personal microbiome compositions. (C) Four subgraphs showing each treatment group in separate subplots using the same coordinate system, coloured by cohort. The shape of points indicates treatment time (pre vs. post), with each individual’s pre- and post-samples connected with a dashed line. Note that only a few individuals exhibit substantial changes in composition between pre- and post-treatment

How Prebiotic Fibers Rewire the Gut for Better Metabolism

Imagine feeding your gut bacteria rather than your own cells this is exactly what happens when you eat prebiotic fibers like inulin and fructooligosaccharides (FOS), which slip past digestion into the colon where microbes feast on them. In this randomized clinical trial, researchers gave overweight/obese and healthy adults daily supplements of inulin or FOS for four weeks and tracked not just blood sugar but also how their gut microbiome shifted in response. The goal was to see if these fermentable fibers could reshape microbial communities in ways that help manage glycemic metabolism.

In overweight and obese participants, inulin stood out: it lowered post-meal glucose levels and altered gut microbial composition. One of the notable microbial changes was a dramatic drop in Ruminococcus a genus of bacteria whose higher presence has been linked in some studies to adverse metabolic outcomes. This reduction correlated with better glucose handling, suggesting that targeting specific microbes through diet could have cascading effects on host metabolism.

Interestingly, both inulin and FOS changed fecal metabolites produced by gut bacteria. Propionate, a key short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) created by the fermentation activities of commensal microbes, decreased significantly after inulin supplementation in both healthy and overweight individuals. SCFAs like propionate are central to how the microbiome influences metabolism: they serve as signaling molecules that can modulate appetite, insulin sensitivity, and inflammation. A shift in their levels reflects deeper changes in microbial fermentation patterns and downstream host responses.

Functional predictions from the bacterial community data also hinted that inulin encouraged pathways linked to microbial folate and glutathione metabolism, which are important for cellular health and antioxidant responses, while FOS appeared to influence purine metabolism. These shifts underscore that prebiotics don’t just feed microbes they redirect the biochemical output of the entire gut ecosystem.

Overall, this study paints a vivid picture of how subtle tweaks in diet can ripple through the gut microbiome, altering specific bacterial groups and metabolic pathways in ways that may benefit metabolic health. By harnessing the fermentative talents of beneficial microbes, inulin and FOS illustrate a broader principle: feeding the microbiome wisely can influence our own metabolism far beyond simple nutrition.