The MicroByte Pathogen Series : Neisseria Meningitidis- Inside the Brain-Invading Bacterium

History

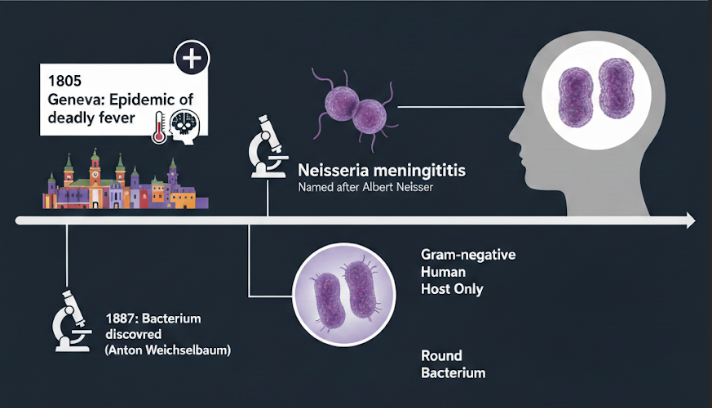

Long before scientists knew what caused it, outbreaks of sudden, deadly fever and brain inflammation terrified communities. In 1805, a doctor named Gaspard Vieusseux described an epidemic in Geneva that killed people within days. It wasn’t until 1887 that the actual bacterium was discovered, when Anton Weichselbaum found it in the fluid surrounding the brain of meningitis patients. The bacterium was later named Neisseria meningitidis after Albert Neisser, a pioneer of bacteriology. Today, we know it as a tiny, round, Gram-negative bacterium that lives only in humans. It exists in several forms, called serogroups, and just a few of them—A, B, C, W, X, and Y—cause the most serious infections around the world.

Transmission

Unlike many germs, N. meningitidis does not spread easily through the air. It usually needs close, personal contact—things like kissing, sharing drinks, or living in the same space. Brief contact, like walking past someone, is not enough to spread it. Both sick people and healthy carriers can pass it on, which is why outbreaks can sometimes seem to come out of nowhere. Places where people live close together—like dormitories, hostels, and military barracks—make it easier for the bacterium to move from person to person.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of N. meningitidis is a sophisticated multistep process that begins with colonization of the human nasopharynx, mediated by Type IV pili (Tfp) for initial attachment and twitching motility, followed by tighter adherence through Opa, Opc, and NadA proteins and the neutralization of mucosal immunity via IgA1 protease. Upon entering the bloodstream, the bacterium ensures its survival using a polysaccharide capsule to mask antigens and Factor H-binding protein (fHbp) to hijack host regulators and inhibit the complement system. The systemic severity of the infection is driven by the shedding of lipooligosaccharide (LOS) endotoxin, which triggers a massive cytokine storm leading to endothelial damage, septic shock, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Finally, the organism crosses the blood-brain barrier by leveraging Tfp to interact with host beta-adrenoceptors, forming cortical plaques that stabilize the bacteria against shear stress and signaling the reorganization of junctional proteins like VE-cadherin, which opens paracellular pathways into the subarachnoid space.

Signs and Symptoms

Meningococcal disease presents a broad clinical spectrum, ranging from classic meningitis—characterized by the clinical triad of sudden high fever, severe headache, and nuchal rigidity (neck stiffness)—to the highly lethal meningococcemia. In meningitis cases, patients often exhibit photophobia, confusion, and nausea, though infants may display more non-specific signs like bulging fontanelles or irritability. When the infection becomes systemic, it manifests as septicemia, hallmarked by a rapidly progressing petechial or purpuric rash that can evolve into purpura fulminans due to microvascular hemorrhage and thrombosis. Severe complications include Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome (acute adrenal hemorrhage), hypotension, and multiorgan failure. Even with successful treatment, survivors frequently face permanent sequelae, such as hearing loss, neurological disabilities.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is often challenging because its initial symptoms frequently mimic less severe conditions, necessitating a high degree of clinical suspicion for early detection. Laboratory confirmation is essential and typically involves demonstrating the presence of the bacteria in normally sterile sites, such as blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), through bacterial culture, which remains the traditional "gold standard" despite taking 24 to 48 hours to yield results. Gram staining provides a more rapid diagnostic tool, identifying the bacteria as distinctive red or pink, coffee-bean-shaped Gram-negative diplococci, and notably, its sensitivity is less affected by prior antibiotic administration than culture methods. For faster and more precise results, real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) is increasingly preferred; it detects specific bacterial DNA sequences within hours and is significantly more sensitive than traditional culturing, especially in patients who have already started treatment. Emerging technologies like Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) further enhance diagnostic capabilities by allowing for detailed strain characterisation and outbreak monitoring, although their widespread use is currently hindered by high costs and the need for specialised infrastructure. Rapid and accurate identification is paramount for effective clinical management and public health responses, given the unpredictable nature and rapid progression of the infection.

Treatment

To treat meningococcal disease, doctors must act fast by giving strong antibiotics directly into a vein. Penicillin G is a common choice, but if someone is allergic, doctors use other drugs like ceftriaxone or cefotaxime. Because the infection can cause the body to shut down, many patients also need intensive care in a hospital. This includes extra oxygen to help with breathing, IV fluids to prevent dehydration, and special medicines to keep their blood pressure from dropping too low. Even though these treatments kill the bacteria, the disease moves so quickly that some survivors are still left with permanent changes like hearing loss or the loss of a limb.

Prevention

When someone is diagnosed, health workers act fast. Family members, roommates, and anyone who had close contact are given preventive antibiotics to stop the bacteria from spreading further. This step is crucial in preventing new cases from appearing. Public health teams also watch carefully for patterns that suggest an outbreak and may recommend extra precautions or vaccinations in certain groups.

Vaccines have changed the story of meningococcal disease. Several vaccines protect against the most dangerous serogroups, and countries that use them widely have seen dramatic drops in cases. Some vaccines protect against groups A, C, W, and Y, while others target group B. Together, they help protect both individuals and entire communities. In parts of Africa, mass vaccination campaigns have nearly wiped out once-regular epidemics.

Also Read: The MicroByte Pathogen Series : Streptococcus pneumoniae –When Common Bacterium Turns Deadly

Microbial Profile

Shape : Diplococcus with a “kidney” or “coffee-bean” shape

Gram nature : Gram Negative

Spore formation : No spore formation

Oxygen requirement : Aerobic

Optimal temperature : 35–37 °C

Optimal pH : 7.0 - 7.6

Laboratory culture media : Blood agar, trypticase soy agar, supplemented chocolate agar, and Mueller-Hinton agar.

Taxonomic Classification

Domain : Bacteria

Kingdom : Pseudomonadati

Phylum : Pseudomonadota

Class : Betaproteobacteria

Order :Neisseriales

Family :Neisseriaceae

Genus : Neisseria

Species : Neisseria meningitidis

-Varsha V

Reference

Rouphael, N. G., & Stephens, D. S. (2012). Neisseria meningitidis: biology, microbiology, and epidemiology. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 799, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-61779-346-2_1

Rausch-Phung EA, Hall WA, Ashong D. Meningococcal Disease (Neisseria meningitidis Infection) [Updated 2025 Jun 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549849/

Ciftci, E., Ocal, D., Somer, A., Tezer, H., Yilmaz, D., Bozkurt, S., Dursun, O. U., Merter, Ş., & Dinleyici, E. C. (2025). Current methods in the diagnosis of invasive meningococcal disease. Frontiers in pediatrics, 13, 1511086. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2025.1511086

Domingo, P., Pomar, V., Mauri, A., & Barquet, N. (2019). Standing on the shoulders of giants: two centuries of struggle against meningococcal disease. The Lancet. Infectious diseases, 19(8), e284–e294. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30040-4

Coureuil, M., Jamet, A., Bille, E., Lécuyer, H., Bourdoulous, S., & Nassif, X. (2019). Molecular interactions between Neisseria meningitidis and its human host. Cellular microbiology, 21(11), e13063. https://doi.org/10.1111/cmi.13063

Qurbanalizadegan, M., Ranjbar, R., Ataee, R., Hajia, M., Goodarzi, Z., Farshad, S., Jonaidi Jafari, N., Panahi, Y., Kohanzad, H., Rahbar, M., Ghadimi, H., & Izadi, M. (2010). Specific PCR Assay for Rapid and Direct Detection of Neisseria meningitidis in Cerebrospinal Fluid Specimens. Iranian journal of public health, 39(4), 45–50.