Holobiome is a blog series that offers an AI-assisted summary of the latest research articles on human microbiome

From Fiber to Function: How Inulin Changes the Gut Microbiome’s Metabolic Signals

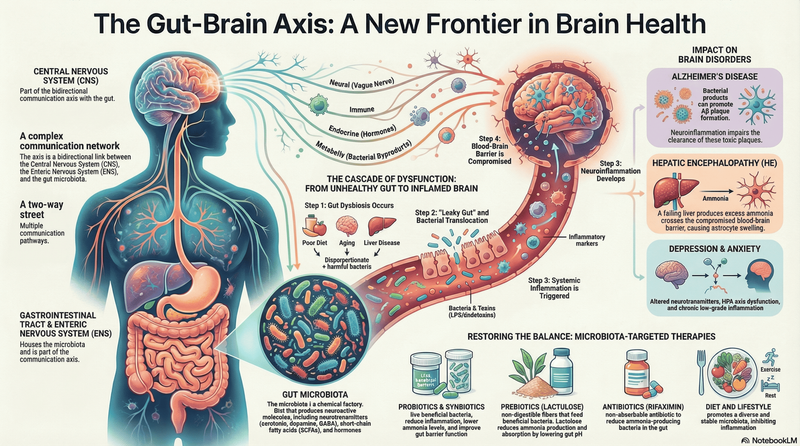

In this fascinating clinical study, researchers looked at how two prebiotic fibers—inulin and fructooligosaccharides (FOS)—shape the ecology of our gut microbiome and, in turn, influence how the body handles sugar. Prebiotics are types of dietary fiber that humans can’t digest but many gut microbes love to eat. By feeding certain microbes, prebiotics can shift the balance of species and their metabolic outputs, with consequences for our own physiology. The trial involved over 130 adults who took inulin, FOS, or a placebo for four weeks, with gut microbiota and metabolic markers measured before and after.

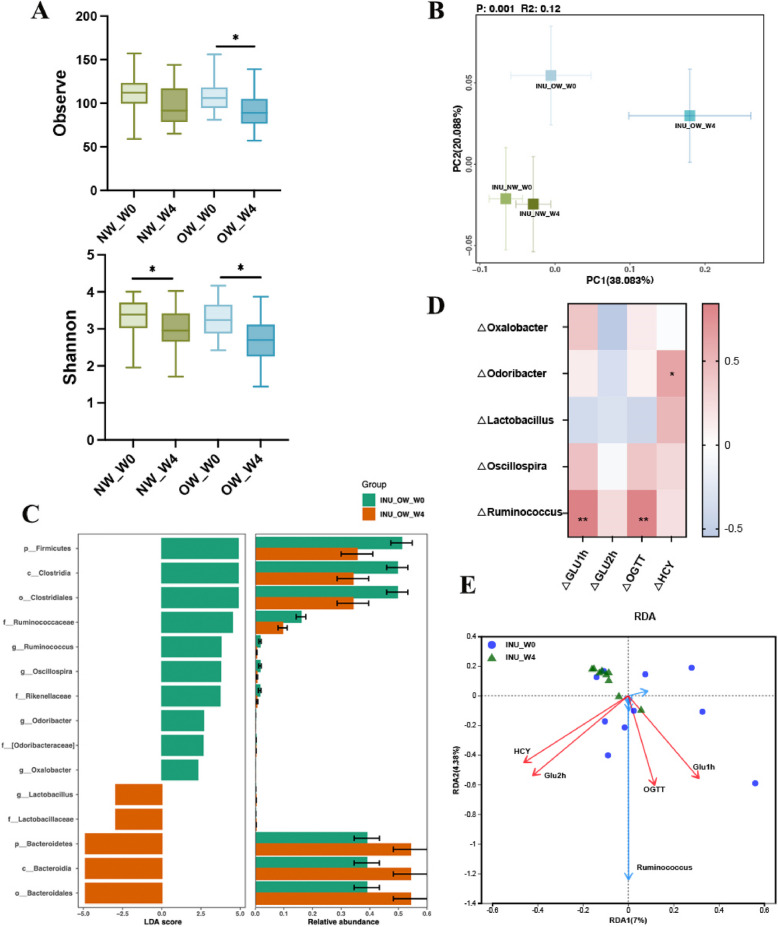

What’s striking from a microbiome perspective is how differently these fibers influenced microbial communities and their byproducts. In overweight and obese participants, inulin supplementation led to meaningful changes in gut bacteria linked to improved glucose metabolism, including a dramatic drop in the relative abundance of Ruminococcus species—microbes often associated with carbohydrate breakdown and fermentation. This shift correlated with better post-meal glucose control and altered insulin responses, suggesting that inulin may help re-tune microbial activity in ways that benefit host metabolism. Interestingly, inulin also reduced fecal propionate, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) produced by many fermentative gut bacteria, hinting at a complex interplay between microbial fermentation end-products and host metabolic signaling.

FOS, by contrast, didn’t have the same glucose-modulating effects, although it did lower homocysteine levels—a marker of metabolic health—without major shifts in glycemic control. From a microbiome mechanistic view, the differences likely relate to how inulin and FOS vary in their fermentation speed and site in the colon, selecting for distinct bacterial guilds and metabolic pathways. Functional predictions from the microbial gene data suggested that inulin enhanced microbe-driven folate and glutathione metabolism, whereas FOS was linked more with purine metabolism.

This study underscores a core idea in microbiome science: feeding the microbiota isn’t just about adding fiber to your diet—it’s about steering the microbial ecosystem toward specific species and metabolic behaviors that can, in turn, influence human health.

Inulin alters gut microbiota composition, which is associated with improved parameters of glycemic metabolism. A Observed species index and Shannon index. B Principal coordinate analysis based on the Weighted Unifrac distance analysis. C LEfSe of the gut microbiota before (W0) and after (W4) inulin intervention in OW groups. D Correlation analysis between significantly changed genus and glucose concentration at 1 h, 2 h, the area under blood glucose concentration curve and HCY. E The redundancy analysis (RDA) that shows the relationships between the significantly changed bacterial community composition at the genus level and the variables for glucose concentration at 1 h, 2 h, AUC OGTT of glucose, and HCY. Data are shown as box plot with whiskers at min/max in A and B, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Feeding the First Microbes: How Blueberries Shape the Infant Gut Ecosystem

When we think about shaping the gut microbiome early in life, what infants eat matters—not just for nutrition, but for the tiny ecosystems taking root in their digestive tracts. In a recent study of breastfed infants transitioning onto complementary foods, researchers explored what happens when you introduce blueberries during this formative window. Far from a simple “fruit vs. no fruit” experiment, this clinical trial asked whether blueberry consumption could influence not only allergy symptoms and immune signals, but also the composition of the gut microbiota itself. Infants who received a daily dose of freeze-dried blueberry powder from around five to twelve months were compared with peers given a placebo.

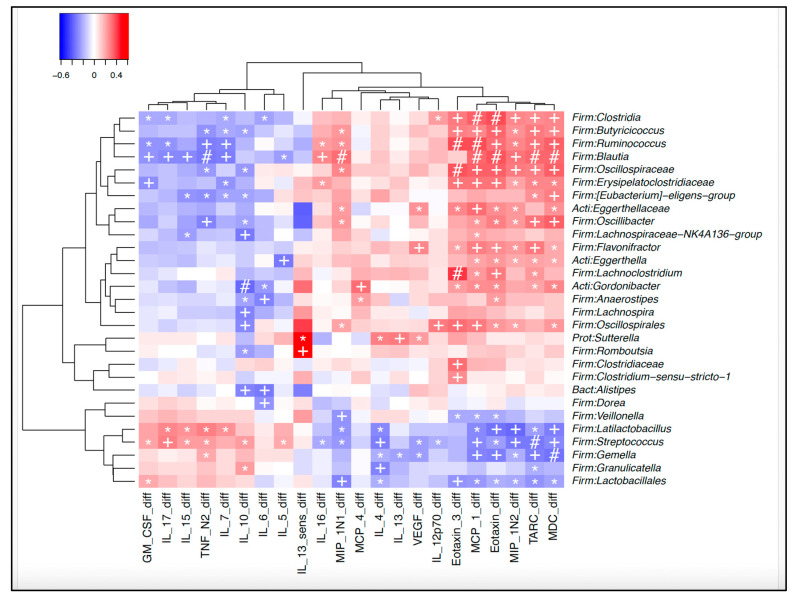

From a microbiome perspective, the findings hint at intriguing ecological shifts. The team found that specific bacterial groups in the infant gut correlated with changes in immune biomarkers: genera like Lacticaseibacillus and Blautia tended to track alongside lower levels of anti-inflammatory IL-10, while Lactobacillus, members of Clostridiaceae, and Megasphaera were associated with higher IL-10. Conversely, the inflammatory cytokine IL-13 showed positive connections with Citrobacter and negative associations with beneficial taxa such as Anaerostipes and Blautia. These patterns suggest that particular microbes may be part of the story linking diet to immune regulation in infancy—even if they don’t explain every twist in allergic symptom trends.

Blueberries are rich in fiber and polyphenols like anthocyanins, compounds that certain gut bacteria can metabolize into bioactive metabolites. Such fermentation not only feeds keystone species like bifidobacteria, which help fortify gut barrier function and outcompete potential pathogens, but also produces short-chain fatty acids and other metabolites that signal to the immune system. Although this trial didn’t conclusively assign causal roles to those metabolites, the associations between microbial taxa and cytokines paint a picture of an evolving gut ecosystem responding to diet during a moment when both microbial communities and immune circuits are highly plastic.

This work underscores a broader theme in microbiome science: early dietary exposures can shape the trajectory of microbial colonization and, through that, potentially tune immune development. As we learn more about which species thrive on which dietary components—and how their metabolic products influence host biology—nutritional strategies like introducing anthocyanin-rich fruits could become tools for nurturing a more resilient gut microbiota from the very start of life.

Heatmap of correlations between microbiota at 12 months and changes in cytokines/chemokines between 5 and 12 months. Legend: Microbiota at 12 months and associated changes in cytokines and chemokines between 5 and 12 months. *: p < 0.05. +: p < 0.01, # p < 0.001.

When Antibiotics Act Like Immunotherapy: The Microbiome’s Role in Cancer Response

In an intriguing twist on how our microbiome might influence systemic health, researchers recently explored whether targeted changes to the gut microbial community could actually boost cancer therapy—specifically for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). At first glance, gut bacteria and lung tumors might seem worlds apart, but this study embraced a growing theme in microbiome science: the microbes in our gut don’t just stay local—they shape immune responses throughout the body, including how well treatments work. Scientists gave patients a gut-restricted antibiotic, oral vancomycin, alongside radiation therapy, with the idea that this drug’s selective action against certain gram-positivebacteria could restructure the gut ecosystem in ways that enhance immune engagement with the tumor.

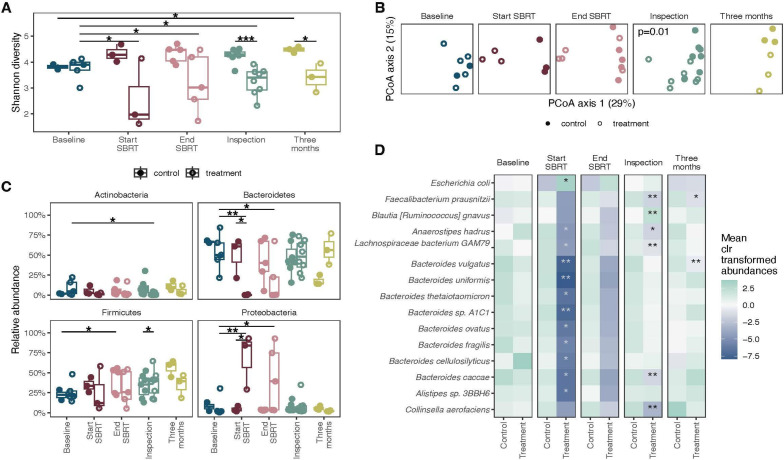

From a microbiome lens, what’s most captivating is how vancomycin selectively depleted and enriched different microbial groups rather than simply wiping out bacteria across the board. This targeted shift led to a discernible restructuring of the gut community, including reductions in bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—metabolites typically linked with anti-inflammatory effects in the colon. That might sound counterintuitive, since SCFAs like butyrate are often thought of as beneficial in gut health, but in the context of immune-driven tumor control, dialing down certain anti-inflammatory signals may actually release the brakes on systemic immune activation.

These microbiome changes were mirrored by systemic immune shifts: indicators of dendritic cell and T-cell activation rose in patients receiving vancomycin, pointing to a gut-mediated boost in immune readiness that could synergize with the radiation’s ability to expose tumor antigens. Notably, these microbial and immune changes correlated with improved clinical outcomes—patients taking vancomycin alongside therapy showed better progression-free and overall survival compared with controls.

This study underscores a powerful concept emerging in microbiome research: the gut microbiota isn’t just a bystander in distant diseases but can be actively modulated to shape treatment efficacy. By tweaking the microbial ecosystem to favor immune engagement, even an antibiotic—often vilified for broad disruption—can be repurposed as a precision toolto enhance how the body fights cancer.

Figure 2. Effect of vancomycin treatment on bacterial abundances. (A) Shannon diversity of samples. (B) Principal coordinate analysis on Bray-Curtis distances of taxonomic abundances of bacteria at the different time points assessed. (C) Relative abundance of four major phyla in the gut. Differences across time were tested using linear mixed effects models, and differences between control and treatment groups were tested using linear models. (D) Mean of center log ratio (clr) transformed abundances at each time point. The stars mark the bacteria that are different between the control and treatment groups for that time point using linear models. ***P<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05. SBRT, stereotactic body radiotherapy.

Searching for Inflammatory Triggers in the Microbial Ecosystem

Imagine a scientific effort that treats the gut microbiome as a window into chronic inflammatory diseases rather than just a side note. That’s the spirit of the INTEGRATE study, an ambitious research program designed to map how the microbial communities in the gut and mouth differ in people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) compared with healthy people. Instead of a single experiment with an endpoint in a lab, this project will follow thousands of participants over several years, collecting saliva, stool, tissue biopsies, and blood to build a detailed picture of how our microbial partners might be entangled with immune-mediated disease processes.

From a microbiome perspective, what makes this work exciting is its scale and depth. Rather than rely solely on relative “who’s there” snapshots, scientists will use full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics to profile the actual species and genes that make up microbial communities in both the mouth and gut. This is critical because dysbiosis—or imbalance—in microbes like Faecalibacterium or Bacteroides has been repeatedly linked to chronic inflammation in IBD, and similar perturbations are suspected in AS. By also doing metabolomics, the team aims to move beyond cataloguing which microbes are present toward understanding what they’re doing—for example, how certain bacteria’s metabolic products might influence immune signalling.

What’s particularly forward-looking is the integration of oral and gut microbiomes with host genetics, clinical history, and environmental data. The researchers will recruit healthy first-degree relatives living in the same households as patients, offering a powerful way to disentangle how much of the microbial signature associated with disease is driven by shared environment versus disease processes themselves. This could help identify pathobionts—organisms harmless in many people but problematic in disease—or microbial metabolites that either drive or dampen chronic inflammation.

While this study is a protocol rather than a report of results, it reflects a broader shift in microbiome research: From asking does the microbiome change in disease? to how do specific microbes and their metabolites interact with the immune system to shape health trajectories?. By following thousands of participants and using multi-omics tools, the INTEGRATE study aims to uncover not just microbial fingerprints of IBD and AS, but mechanisms that might one day be targeted for personalized microbiome-based therapies.

Lighting the Way—and Feeding the Microbes: Probiotics in Neonatal Jaundice Care

In a lively clinical study that bridges neonatal care and microbiome science, researchers tested whether giving beneficial microbes to newborns could help clear one of infancy’s most common conditions—jaundice. Neonatal jaundice arises when a baby’s liver isn’t yet ready to process bilirubin, a yellow pigment that builds up after birth. Typically treated with phototherapy, the standard light therapy helps the body chemicalize bilirubin for elimination. But this study took things a step further by adding two well-studied probiotic strains—Lactobacillus salivarius AP-32 and Bifidobacterium animalissubsp. lactis CP-9—to see if these gut microbes could accelerate the process and support overall gut microbial development in the earliest days of life.

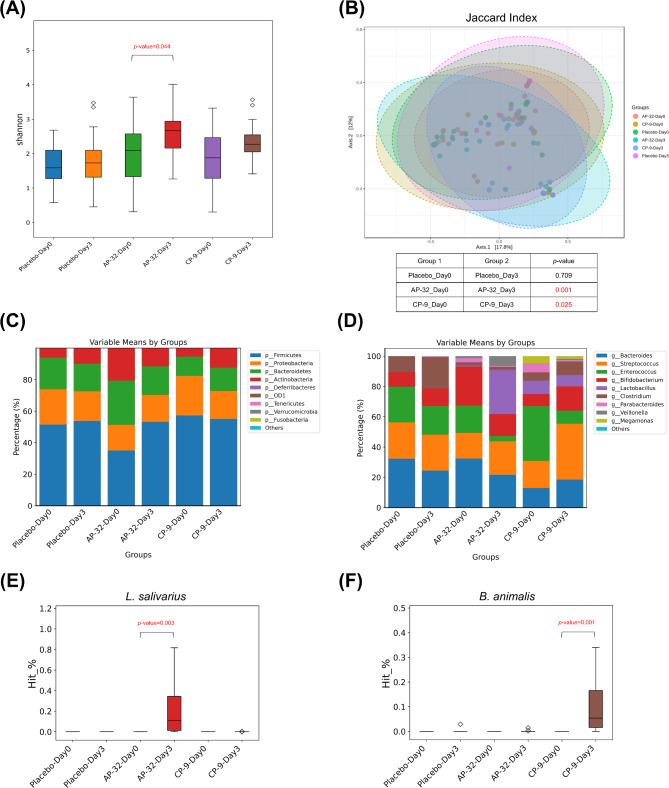

Looking through a microbiome lens, the results were illuminating. Both probiotic groups not only shortened the duration of phototherapy needed to reduce bilirubin levels but also enhanced the diversity and composition of the infants’ gut bacterial communities compared with placebo. Newborns supplemented with L. salivarius showed increases in this species in their stool, while those receiving B. animalis had a corresponding rise in bifidobacteria—genus members often linked with healthy infant guts and the efficient breakdown of sugars and other substrates.

These changes matter because early life is a critical window for microbiome assembly, and establishing a balanced community early can influence digestion, immune education, and metabolic pathways. Bifidobacteria in particular are known to ferment human milk oligosaccharides, lowering gut pH and outcompeting potential pathogens, while lactobacilli support epithelial barrier integrity and may modulate enzymes involved in enterohepatic circulation—the loop of compounds reabsorbed between the gut and liver.

Although the study focused on a specific clinical outcome, it underscores a broader theme in microbiome science: introducing key microbial players at the right time can reshape gut ecosystems and complement medical treatments. For newborns wrestling with jaundice, probiotics might do more than balance bacteria—they could help steer fundamental biochemical pathways that accelerate recovery and support lifelong gut health.

Changes in gut microbiota composition before and after probiotic intervention. Several indices were evaluated, including (A) alpha diversity, (B) beta diversity, the top ten bacterial (C) phyla and (D) genera, as well as the relative abundance of (E) L. salivarius and (F) B. animalis

Stay tuned to unravel the latest discoveries on dynamic human-microbe interactions!