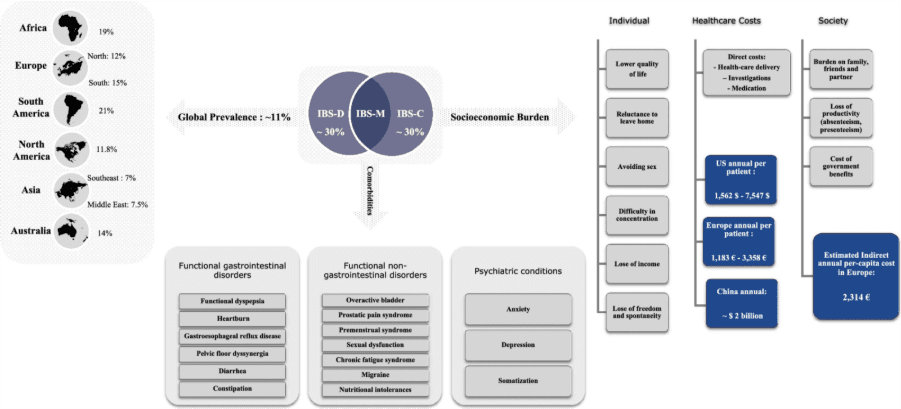

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a chronic gastrointestinal disorder affecting around 10–15% of the global population. It is characterized by abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits (constipation, diarrhea, or both). Despite its high prevalence, IBS has no known cure, and treatment typically focuses on symptom management.

One therapeutic option that has attracted significant research interest is probiotics—live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, may provide health benefits to the host. But how strong is the evidence that probiotics help in IBS?

Figure 1. Global prevalence, comorbidities, and socioeconomic burden of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

The Microbiome and IBS

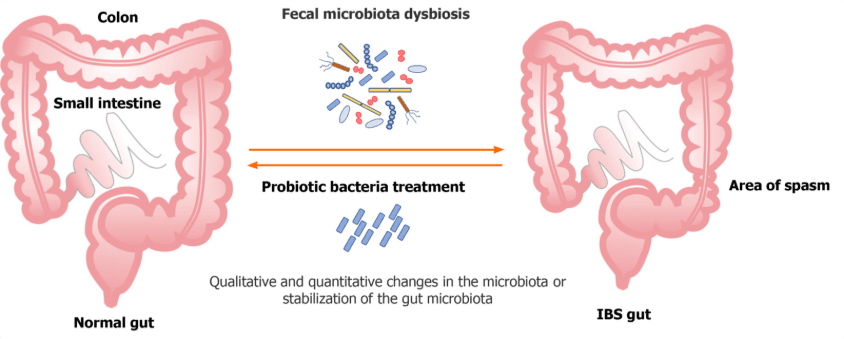

Over the past two decades, evidence has increasingly implicated the gut microbiota in IBS pathophysiology. Patients with IBS often display dysbiosis, or alterations in gut microbial composition, including reduced levels of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, and increased levels of potentially pathogenic species.

These microbial imbalances can:

- Disrupt intestinal barrier integrity, contributing to increased permeability (“leaky gut”).

- Trigger low-grade mucosal inflammation through altered immune activation.

- Influence gut motility and sensitivity via the gut–brain axis, partly mediated by microbial metabolites and neurotransmitters.

Given this, probiotics are hypothesized to restore microbial balance, reduce inflammation, and modulate gut–brain communication in IBS.

Figure 2. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Schematic overview of the main mechanisms contributing to IBS. Factors include microbial dysbiosis (reduced Bifidobacterium and Faecalibacterium, increased Proteobacteria and Firmicutes), impaired intestinal barrier integrity, low-grade mucosal inflammation, altered motility, and disturbed microbiota–gut–brain axis signaling. These mechanisms provide the biological rationale for probiotic interventions aimed at restoring balance and reducing IBS symptoms.

Evidence from Clinical Trials

Early-Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews

A meta-analysis of 20 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 1,404 IBS patients reported that probiotics were associated with significant improvement in global IBS symptoms and abdominal pain compared to placebo. A 2018 update by Ford et al included 53 RCTs and found probiotics reduced the persistence of IBS symptoms and improved abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence. However, heterogeneity across studies prevented identification of a single effective strain or optimal dose. The British Dietetic Association also concluded that probiotics can improve IBS symptoms but emphasized that no specific strain or dose could be universally recommended.

Latest Evidences

A 2021 review highlighted the inconsistency of results: some RCTs showed benefits for bloating and pain, while others showed no effect (Benjak Horvat et al., 2021). A 2022 commentary further stressed that the probiotic market is poorly regulated, and many commercial products do not meet scientific standards (Quigley, 2022). However, a recent double-blind trial showed a ~50-point reduction in IBS Symptom Severity Score (IBS-SSS) with probiotics vs ~20 with placebo, suggesting a clinically meaningful effect (Li et al., 2025). A 12 week-RCT showed that the blend of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium improved intestinal barrier proteins (occludin, claudin-1), reduced inflammation (CRP, IL-6, TNF-α), boosted short-chain fatty acids, and significantly reduced IBS severity scores across subtypes (Li et al., 2025). Studies have confirmed that the probiotics are effective in alleviating the symptoms of IBS especially when combined with prebiotics (Wu et al., 2024; Almabruk et al., 2024). Recent studies also suggest that a low-FODMAP diet combined with probiotics provided the greatest symptom relief, outperforming probiotics alone.(Ding et al., 2025).

Strain-Specific Effects

Not all probiotics act the same way. Clinical data suggest that efficacy is strain- and condition-specific:

- Bifidobacterium infantis 35624: Some trials demonstrated improvement in abdominal pain and bloating, though results were not consistently superior to placebo (Ooi et al., 2019).

- Lactobacillus strains: Some meta-analyses suggest modest improvements, particularly in bloating.

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae CNCM I-3856: Demonstrated significant pain reduction in limited trials.

- Multi-strain probiotics: Some studies show benefit, though variability in strain composition makes conclusions difficult. (Mazurak et al., 2015).

Mechanisms of Action

Probiotics may exert benefits in IBS through several mechanisms:

- Restoring microbial balance – increasing Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, reducing pathogenic species.

- Enhancing epithelial barrier function – improving tight junction integrity and reducing intestinal permeability.

- Modulating immune activity – downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines, reducing mucosal inflammation.

- Gut–brain axis modulation – producing neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin, GABA) and short-chain fatty acids that influence motility and visceral sensitivity.

Limitations of Current Evidence

Despite promising findings, several limitations remain:

- Heterogeneity: Trials vary widely in probiotic strain, dosage, and duration, limiting comparability.

- Short-term data: Most trials last 4–8 weeks; long-term efficacy is unknown.

- Subtype differences: IBS subtypes (IBS-D, IBS-C, IBS-M) may respond differently, but studies rarely stratify results.

- Regulatory gaps: Many commercial products marketed as “probiotics” have not been tested in rigorous trials (Quigley, 2022).

Clinical Recommendations

Based on current evidence:

- Probiotics are safe and may provide symptom relief, especially for abdominal pain and bloating.

- No universal recommendation can be made for a specific strain or dose. Trial-and-error with one product at a time for 4–8 weeks is reasonable.

- Personalized approaches considering IBS subtype, symptom profile, and patient response are needed.

- Adjunctive role: Probiotics should complement, not replace, dietary (e.g., low FODMAP diet) and lifestyle interventions.

Conclusion

So, do probiotics help IBS? The evidence suggests they can—but not consistently, and not for everyone. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews confirm improvements in global symptoms and abdominal pain, yet variability between strains and patients prevents clear guidelines.

Emerging 2024–2025 studies are encouraging, particularly those showing improvements in intestinal barrier function, inflammation, and symptom scores. For now, probiotics should be considered a safe, adjunctive option in IBS management, ideally introduced under professional guidance. As research evolves, future studies targeting specific IBS subtypes with standardized strains may allow more precise, evidence-based recommendations.

-Kamala M

References

Almabruk, B. A., Bajafar, A. A., Mohamed, A. N., Al-Zahrani, S. A., Albishi, N. M., Aljarwan, R., … Alsolami, A. S. (2024). Efficacy of probiotics in the management of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus, 16(12), e75954. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.75954

Benjak Horvat, I., Gobin, I., Kresović, A., & Hauser, G. (2021). How can probiotics improve irritable bowel syndrome symptoms? World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, 13(9), 923–940. https://doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i9.923

Ding, L., Duan, J., Yang, T., Yuan, M., Ma, A. H., & Qin, Y. (2025). Efficacy of fermented foods in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, Article 1494118. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1494118

Harper, A., Naghibi, M. M., & Garcha, D. (2018). The role of bacteria, probiotics and diet in irritable bowel syndrome. Foods, 7(2), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7020013

Li, E., Wang, J., Guo, B., & Zhang, W. (2025). Effects of short-chain fatty acid-producing probiotic metabolites on symptom relief and intestinal barrier function in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 15, Article 1616066. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2025.1616066

Mazurak, N., Broelz, E., Storr, M., & Enck, P. (2015). Probiotic therapy of the irritable bowel syndrome: Why is the evidence still poor and what can be done about it? Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 21(4), 471–485. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm15071

McFarland, L. V., & Dublin, S. (2008). Meta-analysis of probiotics for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 14(17), 2650–2661. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.2650

Ooi, S. L., Correa, D., & Pak, S. C. (2019). Probiotics, prebiotics, and low FODMAP diet for irritable bowel syndrome—What is the current evidence? Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 43, 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2019.01.010

Quigley, E. M. M. (2022). Clinical trials of probiotics in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: Some points to consider. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 28(2), 204–211. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm22012

Wu, Y., Li, Y., Zheng, Q., & Li, L. (2024). The efficacy of probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Nutrients, 16(13), 2114. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132114