Feeding the Phages: How Your Diet Shapes the Gut's Viral World

While we think of food as fuel for our body, the food we eat also fuels another hidden world in the gut: our microbiota!

Ever notice how you feel gassy and irritated after a heavy meal of burger and fries, but light and peaceful after a warm, home-cooked meal? That's those tiny friends—our microbiota—sending signals to your brain and body. How they respond to the food we consume is key to whether we stay healthy or invite disease.

While bacteria usually steal the limelight, today we're focusing on the phages. You might remember from our previous blog that phages (viruses that attack bacteria) play a crucial role in keeping the bacterial population in check. If you missed that introduction, you can check it out with this link before diving in!

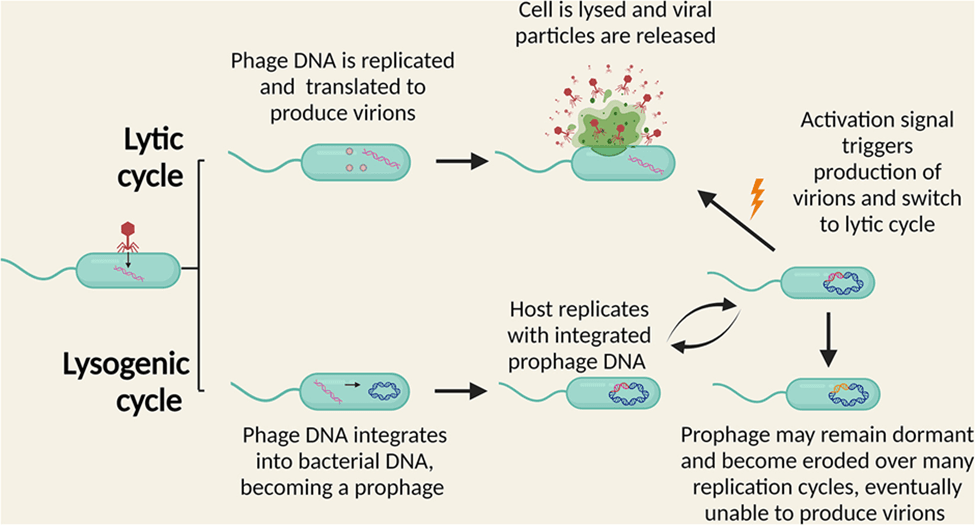

Before we proceed further, it’s important to understand the two types of phage behavior in our gut:

● Lytic cycle - attack mode

● Lysogenic cycle - hibernation mode

Source: https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(24)00056-1

The Lytic Cycle (Attack Mode)

In this phase, the phages enter the bacterial cell and take control of the system. They replicate themselves into many new phages, then burst open the bacterial cell, killing it and infecting many others. That's the attack mode.

The result? Rapid destruction of bacteria, which can quickly alter the bacterial population and affect your digestion and overall health.

The Lysogenic Cycle (Hibernation Mode)

This is a much more peaceful phase. The phage integrates its DNA into the bacterial genome, becoming a prophage. It replicates itself but doesn't kill the bacteria; it just stays inside while the bacteria divides.

The result? Peaceful coexistence with the bacteria, which means minimal risk of dysbiosis (imbalance).

Food as a Trigger

The type of food we eat literally decides which cycle the phage chooses. For example, a diet high in refined foods, fat, and sugar directly causes a major shift in the bacterial population.

Studies in mice show that when they chow down on high-fat, high-sugar meals, certain types of phages spike, especially near the gut lining. Over time, this causes the normally “quiet” viruses (prophages) that coexist peacefully to wake up and start the lytic cycle.

This switch can lead to less variety in gut bacteria, upsetting the balance and potentially contributing to issues like inflammation and metabolic problems. What’s wild is that these viral changes can happen even faster than bacterial ones, showing just how sensitive this hidden world inside us is to what’s on our plate.

Think of your gut like a city where bacteria are the residents and phages are undercover agents. When you eat plenty of fiber, it’s like keeping the grocery stores stocked—everyone’s happy, and the agents stay low-key. Cut the fiber and load up on fatty, sugary junk food, and suddenly the shelves run bare. The stressed-out bacteria wake the undercover agents who then stir things up, breaking down some bacteria and disrupting the balance. So, your diet literally decides whether the gut stays peaceful or turns into a wild party.

The SCFA - Diet - Phage Link

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—like acetate, propionate, and butyrate—are produced when gut bacteria ferment dietary fiber. They’re usually seen as health heroes: they support the microbiome and strengthen the intestinal barrier. Low SCFA levels are often linked to gut issues like leaky gut and IBD.

But here’s the interesting part: studies show that SCFAs can trigger those dormant prophages inside bacteria to activate and produce more phages, sometimes without harming the bacteria themselves! Since high-fiber diets boost SCFA production, they may indirectly increase prophage activity.

Even if full phages aren’t produced, SCFAs can still activate phage-related genes, suggesting they play a much bigger, more complex role in regulating gut viruses than we realized. In a balanced gut, this interaction probably helps maintain harmony. But in a stressed or unbalanced gut, it could tip the scales toward inflammation or disease.

Specific Foods and Their Phage Effects

The good news is that many common food components have a direct effect on phage activity:

● Polyphenols (tea, coffee, berries, soy): Can damage phage structures and interfere with replication, reducing their ability to infect.

● Essential Oils (chamomile, lemongrass, cinnamon): Show clear antiviral effects against phages.

● Natural Sweeteners: It's a mixed bag! Stevia can selectively activate prophages in some bacteria, while others, like aspartame or propolis, seem to have the opposite effect.

● Juices & Extracts (cranberry, blueberry, pomegranate, potato, tomato): Can reduce phage infectivity, often by messing with replication or damaging viral DNA.

● Chitosan (from shellfish and fungi): Can significantly reduce phage activity and toxin expression in pathogenic bacteria.

It's clear that diet plays a crucial role in shaping the gut’s viral ecosystem, influencing how phages and bacteria interact. Understanding these intricate relationships opens new doors for dietary strategies aimed at gut health and disease prevention.

Future therapies could harness specific nutrients to activate or suppress phage activity, helping manage conditions like IBD, obesity, or even cancer. With personalized nutrition and virome-aware interventions on the horizon, the next frontier in gut health might be less about what we eat—and more about how it shapes our invisible viral allies.

-Rohini Prasad

References

Howard, A., Carroll-Portillo, A., Alcock, J., & Lin, H. C. (2024). Dietary Effects on the Gut Phageome. International journal of molecular sciences, 25(16), 8690. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25168690

Kirk, D., Costeira, R., Visconti, A., Khan Mirzaei, M., Deng, L., Valdes, A. M., & Menni, C. (2024). Bacteriophages, gut bacteria, and microbial pathways interplay in cardiometabolic health. Cell reports, 43(2), 113728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.113728

Townsend, E. M., Kelly, L., Muscatt, G., Box, J. D., Hargraves, N., Lilley, D., & Jameson, E. (2021). The Human Gut Phageome: Origins and Roles in the Human Gut Microbiome. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 11, 643214. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.643214

Shkoporov, A. N., & Hill, C. (2019). Bacteriophages of the Human Gut: The "Known Unknown" of the Microbiome. Cell host & microbe, 25(2), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2019.01.017