The MicroByte Pathogen Series : Streptococcus pneumoniae –When Common Bacterium Turns Deadly

History

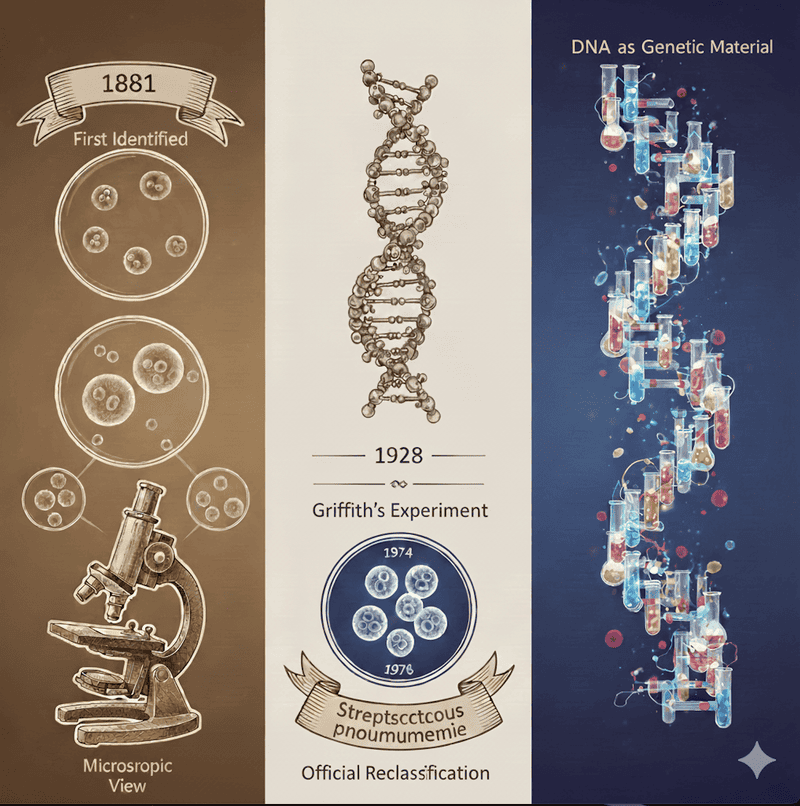

Streptococcus pneumoniae has a long and influential history that closely mirrors the development of modern microbiology and genetics. The bacterium was first identified in 1881 by two scientists working independently, Louis Pasteur in France and George M. Sternberg in the United States, both isolating it from the saliva of patients with pneumonia. Early names reflected this origin, but by the late 19th century it became widely known as the “pneumococcus” after being firmly linked to lobar pneumonia, a disease that was often fatal before antibiotics. At the time, the physician Sir William Osler famously described pneumonia as “the captain of the men of death.”

Beyond medicine, S. pneumoniae played a landmark role in biology. In 1928, experiments using pneumococcal strains revealed that bacteria could transfer traits between one another, a phenomenon later shown to be driven by DNA. This discovery provided the first clear proof that DNA is the genetic material. As scientific understanding advanced, the bacterium was reclassified based on genetic relationships, and since 1974 it has been officially known as Streptococcuspneumoniae. Today, it remains both a major human pathogen and a foundational organism in biological research.

Transmission

Streptococcus pneumoniae spreads mainly through respiratory droplets released when people cough, sneeze, or speak. Importantly, many transmissions occur from people who are not sick. Healthy carriers, especially children often harbor the bacterium in their upper airways without symptoms and unknowingly pass it to others. Carriage is particularly common in daycare and school settings, where close contact makes spread easier.

Crowded environments, seasonal viral infections, and close household contact all increase transmission. Rates tend to rise during winter months, when people spend more time indoors and respiratory infections are more common. Although the bacterium does not survive long on surfaces, it spreads efficiently through direct person-to-person contact. Colonization usually comes first, and disease develops when the bacteria spread from their usual location to more vulnerable parts of the body.

Pathogenesis

Streptococcus pneumoniae often lives quietly in the nose and throat, especially in young children, without causing illness. Problems arise when the bacterium moves beyond this normal niche. Factors such as viral infections, weakened immunity, or aging can allow it to spread to areas that are normally sterile, including the lungs, middle ear, bloodstream, or brain coverings. Once established in these sites, the bacteria multiply quickly and trigger a strong inflammatory response.

A major reason the bacterium can cause disease is its capsule, which helps it escape detection by immune cells. It also produces substances that damage host tissues and intensify inflammation. While these responses help the body fight infection, they also cause many of the symptoms of pneumococcal disease. Whether S. pneumoniae remains harmless or becomes dangerous depends on the balance between bacterial traits and the host’s immune defenses.

Signs and Symptoms

Pneumococcal infections range from mild to life-threatening, depending on where the infection occurs and who is affected. Many cases involve the respiratory tract, reflecting the bacterium’s natural habitat. The most common serious illness is pneumococcal pneumonia, which often begins suddenly with high fever, chills, cough, chest pain, and difficulty breathing. A classic sign is rust-colored or blood-tinged sputum, caused by inflammation in the lungs.

The bacterium is also a leading cause of ear and sinus infections, especially in children, where symptoms include ear pain, fever, irritability, facial pressure, and nasal discharge. More severe disease occurs when the bacteria enter the bloodstream or nervous system. Pneumococcal meningitis can cause intense headache, stiff neck, confusion, and seizures, and may result in death or long-term complications. Severe illness is most common in young children, older adults, and people with chronic medical conditions.

Diagnosis

Doctors often suspect pneumococcal disease based on symptoms such as sudden fever, cough with colored sputum, chest pain, or signs of meningitis. Imaging studies, like chest X-rays, help support the diagnosis of pneumonia, but laboratory tests are needed to confirm the cause.

Confirmation involves detecting the bacterium in clinical samples such as blood or spinal fluid, or identifying its components using rapid tests. Modern diagnostic tools can detect pneumococcal material even when antibiotics have already been started. Alongside identifying the bacteria, clinicians assess how severe the illness is using imaging, oxygen levels, and blood tests. Together, these approaches allow timely diagnosis and guide effective treatment.

Treatment

The introduction of antibiotics dramatically improved outcomes for pneumococcal infections. Many uncomplicated cases, such as pneumonia, ear infections, or sinusitis, respond well to commonly used antibiotics when treatment is started early. Most patients recover fully with appropriate care.

Severe infections such as meningitis or bloodstream infections require hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics, along with supportive care like oxygen and fluids. Over time, some pneumococcal strains have become resistant to certain antibiotics, making careful drug selection more important. Doctors now tailor treatment based on illness severity and local resistance patterns. Despite these challenges, pneumococcal disease remains largely treatable with prompt and appropriate therapy.

Prevention

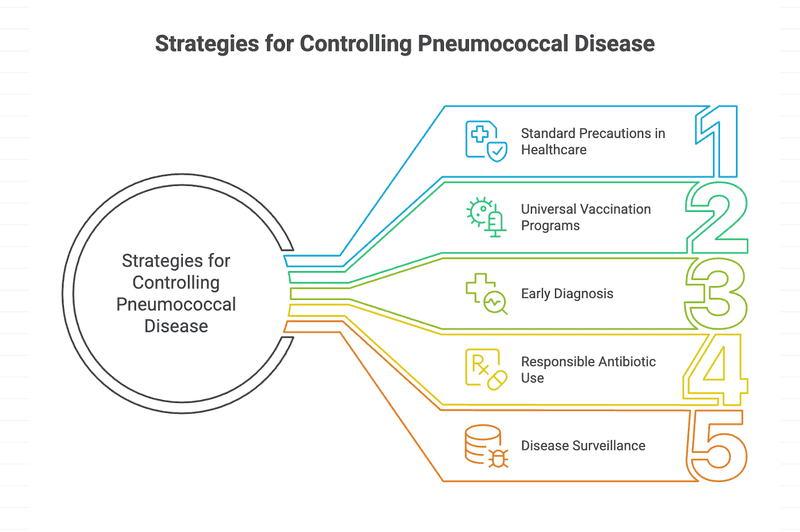

Preventing pneumococcal disease relies on vaccination combined with healthy living conditions and protection of high-risk groups. Good nutrition and exclusive breastfeeding during infancy strengthen immunity and lower the risk of pneumonia. Environmental factors also matter: reducing indoor air pollution, avoiding tobacco smoke, improving ventilation, and minimizing overcrowding can significantly decrease transmission.

People at highest risk including infants, older adults, and those with chronic illnesses benefit most from preventive strategies. Managing underlying health conditions and seeking early medical care when symptoms arise can prevent complications. Together, vaccines, healthy environments, good nutrition, and early care form a strong foundation for prevention.

Vaccines

Vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae has been one of the most effective tools for reducing pneumonia, meningitis, and bloodstream infections worldwide. Two main vaccine types are used, both targeting the bacterium’s outer capsule. Older polysaccharide vaccines are mainly used in adults to prevent severe invasive disease, while newer conjugate vaccines are designed to work well in infants and young children.

Conjugate vaccines have had a particularly dramatic impact. They protect children directly and also reduce bacterial carriage in the nose, lowering transmission within communities. This creates herd immunity, protecting unvaccinated groups such as older adults. Countries that introduced these vaccines saw sharp declines in hospitalizations and deaths across all age groups. Newer vaccines now cover an even broader range of strains, further strengthening protection worldwide.

Also Read: The MicroByte Pathogen Series : Clostridum botulinum- Botulinum Paradox

Microbe Profile

Shape : Slightly elongated cocci, typically appearing in pairs (diplococci)

Gram nature : Gram-positive

Spore formation : No

Biofilm formation : Capable of forming biofilms, particularly in the human respiratory tract

Oxygen requirement : Facultative anaerobe

Optimal temperature : 35–37 °C (human body temperature)

Optimal pH : Near neutral pH (around 7.2–7.6)

Nutrient usage / Laboratory culture media : Grows best in nutrient-rich environments; commonly cultured on blood agar, where it forms small colonies showing alpha-hemolysis (greenish discoloration)

Taxonomic Classification

Domain : Bacteria

Kingdom : Bacillati

Phylum : Bacillota

Class :Bacilli

Order :Lactobacillales

Family : Streptococcaceae

Genus : Streptococcus

Species :Streptococcus pneumoniae

-Neha Rao

References

Henriques-Normark, B., & Tuomanen, E. I. (2013). The pneumococcus: epidemiology, microbiology, and pathogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 3(7), a010215. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a010215

Yesilkaya, Hasan & Oggioni, Marco Rinaldo & Andrew, Peter. (2022). Streptococcus pneumoniae: ‘captain of the men of death’ and financial burden. Microbiology. 168. 10.1099/mic.0.001275.

Petsko G. A. (2006). Transformation. Genome biology, 7(10), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-117

Facklam R. (2002). What happened to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clinical microbiology reviews, 15(4), 613–630. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.15.4.613-630.2002

Weiser, J. N., Ferreira, D. M., & Paton, J. C. (2018). Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nature reviews. Microbiology, 16(6), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0001-8

Marquart M. E. (2021). Pathogenicity and virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Cutting to the chase on proteases. Virulence, 12(1), 766–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.1889812

Brooks, L. R. K., & Mias, G. I. (2018). Streptococcus pneumoniae's Virulence and Host Immunity: Aging, Diagnostics, and Prevention. Frontiers in immunology, 9, 1366. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01366

Nagaraj, S., Kalal, B. S., Manoharan, A., & Shet, A. (2017). Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype prevalence and antibiotic resistance among young children with invasive pneumococcal disease: experience from a tertiary care center in South India. Germs, 7(2), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2017.1112

El Zein, Z., Nasser, M., Boutros, C. F., Tfaily, N., Reslan, L., Faour, K., Merhi, S., Damaj, S., Moumneh, M. B., Bou Dargham, T., Youssef, N., Haj, M., Bou Karroum, S., Khafaja, S., Assaf Casals, A., Chamseddine, S., Hneiny, L., & Dbaibo, G. S. (2025). Changing Landscape of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Serotypes and Antimicrobial Resistance Following Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Introduction in the Middle East and North Africa Region: A Systematic Review. Vaccines, 13(9), 923. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13090923

Shawrob, K. S. M., Dhariwal, A., Salvadori, G., Gladstone, R. A., & Junges, R. (2025). Large-scale global molecular epidemiology of antibiotic resistance determinants in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microbial genomics, 11(7), 001444. https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.001444

Kumar K L, R., Ganaie, F., & Ashok, V. (2013). Circulating Serotypes and Trends in Antibiotic Resistance of Invasive Streptococcus Pneumoniae from Children under Five in Bangalore. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR, 7(12), 2716–2720. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2013/6384.3741

Dhawale, P., Shah, S., Sharma, K., Sikriwal, D., Kumar, V., Bhagawati, A., Dhar, S., Shetty, P., & Ahmed, S. (2025). Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype distribution in low- and middle-income countries of South Asia: Do we need to revisit the pneumococcal vaccine strategy?. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 21(1), 2461844. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2025.2461844

Chen, C. H., Chen, C. L., Su, L. H., Chen, C. J., Tsai, M. H., & Chiu, C. H. (2025). The microbiological characteristics and diagnosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in the conjugate vaccine era. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 21(1), 2497611. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2025.2497611