Holobiome is a blog series that offers an AI-assisted summary of the latest research articles on human microbiome.

Gut Feeling: Sauerkraut Shows Promise in Supporting Microbiome Health

A recent pilot study explored the gut health benefits of sauerkraut—a fermented cabbage dish often praised in traditional diets. Participants in the study consumed about 100 grams of unpasteurized sauerkraut daily for six weeks, while researchers tracked changes in their gut microbiota and metabolic markers through stool samples. The goal was to see if this everyday fermented food could measurably shift gut bacteria and improve digestion.

The results showed subtle but encouraging changes. Two beneficial bacterial groups—Prevotella and Phascolarctobacterium—increased in abundance. These microbes are known for aiding digestion and producing short-chain fatty acids like propionate, which support gut health and reduce inflammation. There was also a potential rise in Akkermansia, a bacterium linked to a healthy gut lining and metabolic stability. While participants reported mild improvements in digestion and regularity, these self-reported outcomes weren’t statistically significant.

Still, the microbial shifts suggest that sauerkraut might gently steer the gut microbiome in a positive direction. Researchers stress that the study was small and lacked a control group, so the findings are preliminary. However, the results support the growing belief that simple fermented foods can promote gut wellness. Larger, controlled studies are needed, but this work adds to the case for including foods like sauerkraut in a gut-friendly diet.

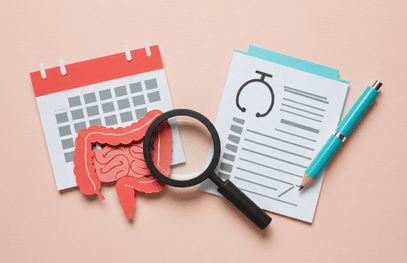

Overview of the study procedure; vials indicate stool and serum sampling, 24 h recalls of consumed foods the day before stool sampling were recorded online; FFQ = food frequency questionnaire.

Smarter Gut, Lower Blood Pressure? New Study Explores Fecal Microbiota Transplants (FMT) in Hypertension

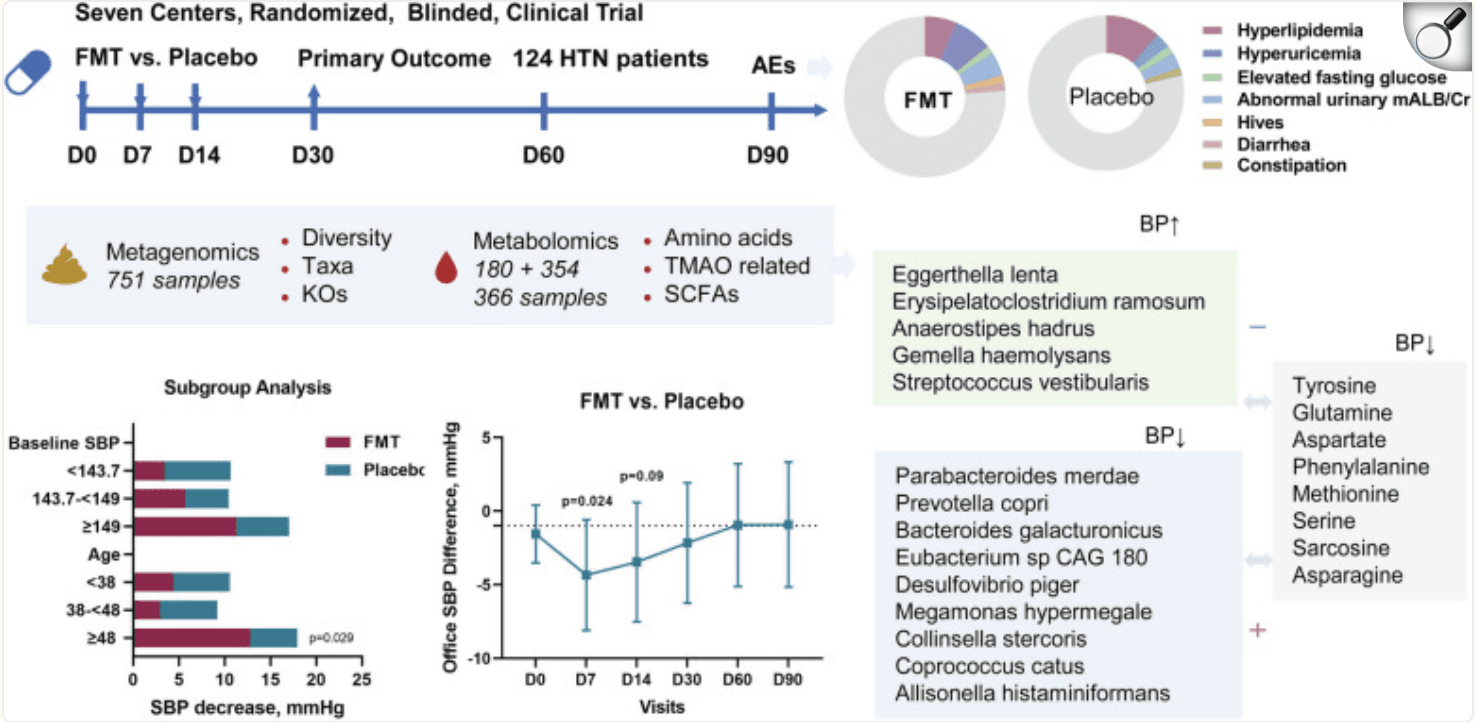

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in China tested whether transplanting healthy microbes via oral capsules could help people with high blood pressure. Between March and December 2021, 124 adults with Stage 1 hypertension received freeze-dried FMT capsules (63 people) or placebo (61 people) on days 1, 7, and 14, with follow-up at day 30 for blood pressure (BP) and safety checks.

The results showed that FMT was safe—adverse events were mild and occurred in 20.6% of the FMT group vs 14.8% in the placebo group (p = 0.39). Blood pressure drops were similar by day 30: a 6.3 mmHg reduction for FMT vs 5.8 mmHg for placebo (no statistical significance, p = 0.62). However, one week after starting treatment, the FMT group had a significantly larger drop in systolic BP—4.3 mmHg more than placebo (p = 0.024). This early benefit faded over time.

Deep analysis of fecal and plasma samples revealed shifts in gut bacteria: blood pressure–linked species like Parabacteroides merdae, Prevotella copri, Bacteroides galacturonicus, and Desulfovibrio piger rose, while others such as Eggerthella lenta, Erysipelatoclostridium ramosum, Anaerostipes hadrus, Gemella haemolysans, and Streptococcus vestibularis declined. These changes also correlated with metabolites like tyrosine, glutamine, and phenylalanine.

In short, this is the first clinical trial suggesting that FMT might safely nudge blood pressure downward—especially early on—via shifts in gut microbes and their metabolic products. While the benefits were not sustained, the study paves the way for future microbe-targeted treatments in hypertension.

Structured graphical abstract of the study. This is the first multicenter randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial to explore the safety and efficacy of FMT in treating hypertension. FMT via oral capsules is safe for hypertension treatment, with self-limiting or mild AEs observed, and is comparable with the placebo. However, FMT has only a 1-week BP-attenuating effect that is eliminated with intervention termination and does not support our hypothesis for the primary outcome of office SBP change at the day- 30 follow-up. Alterations and interactions of 8 genera, 14 species, 97 KOs, and 8 amino acids in response to FMT and with BP-affecting features were identified via multiomics analysis of metagenomic, untargeted and targeted metabolomic data.

Microbial Diversity and Mental Health: Insights from a Probiotic Trial

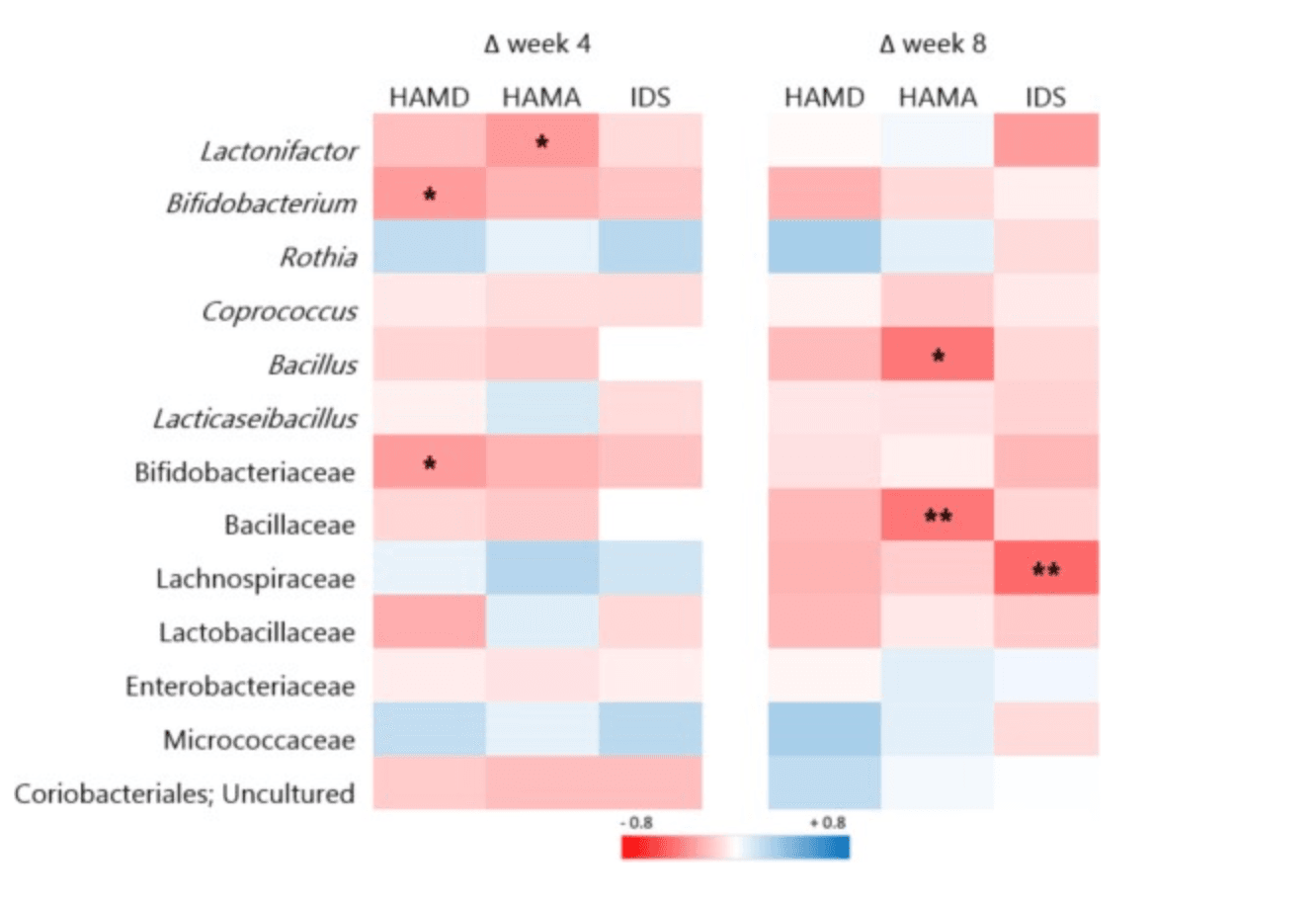

A recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial looked at how multi‑strain probiotics could help people with major depressive disorder (MDD). Over eight weeks, 49 participants on antidepressants were randomized to daily probiotics (24 people) or placebo (25 people), and researchers collected stool and blood samples to explore changes in gut bacteria and inflammatory markers. A group of 25 healthy volunteers was also analyzed for baseline comparison.

The probiotic group showed a significant increase in microbial richness by week 4 (Chao1 index, p = 0.04) and trends toward greater total bacterial counts at weeks 4 and 8 compared to baseline—but not significantly more than placebo. In contrast, the placebo group’s post-treatment gut diversity (Shannon entropy) dropped significantly compared to healthy controls (p = 0.03), while the probiotic group maintained healthier diversity levels. Additionally, microbiome composition (beta diversity) differed significantly between probiotic and placebo groups at week 4 (p = 0.04). A notable increase in the bacterial family Bacillaceae was observed post-treatment in the probiotic arm—and this change correlated with reductions in anxiety symptoms. However, there were no changes in circulating inflammatory cytokines.

In short, this pilot study suggests multi‑strain probiotics may support gut microbial diversity and potentially ease anxiety in people with depression—but without affecting inflammation. While preliminary, these findings offer insight into the gut–brain connection and highlight microbial diversity and specific bacteria families (like Bacillaceae) as possible mediators. Further large-scale trials are needed to confirm these effects and clarify how probiotics could benefit mental health.

Correlations between microbial changes and changes in clinical outcomes. * significant according to uncorrected p values (p < 0.05); ** significant according to FDR corrected p values (p < 0.05). The strength of the correlation (Spearman's rho) is indicated by the colour gradient, with red for negative and blue for positive correlations; week 4: n = 42 (n = 21 probiotic, n = 21 placebo); week 8: n = 36 (n = 19 probiotic, n = 17 placebo). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Boost or Barely Any Change? Exploring Probiotics’ Role in Crohn’s Health

A new multicenter, randomized, single-blind trial in Beirut investigated whether a probiotic mix could help adults with Crohn’s disease (CD). Over two months, 21 patients were split into two groups: one received a daily probiotic supplement containing Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, and Lactococcus, while the other followed regular care. Researchers tracked disease progression, quality of life (QOL), nutrient intake, and body composition at the start and end of the study.

Although the probiotic group didn’t experience fewer symptoms, flare-ups, or hospital visits compared to controls, they did see positive changes in body composition and nutrient intake. Specifically, they gained weight, BMI, body fat, and muscle circumference, while also consuming more calcium, riboflavin, folate, fiber, sugar, and caffeine. In addition, quality of life improved significantly in the probiotic group—especially in physical, psychological, and environmental wellbeing—while the control group only saw psychological gains. Mild side effects like nausea and abdominal discomfort were reported, but no serious issues emerged.

In summary, this trial suggests probiotics may support nutritional status, body composition, and quality of life in Crohn’s patients—even if they don’t directly influence disease activity. These promising findings, though from a small sample, highlight the potential of probiotic supplements as helpful tools in managing Crohn’s. Still, larger, longer studies are needed to confirm these benefits and determine optimal dosing.

Targeting Gingivitis: Toothpaste Ingredients and Subgingival Microbiome Shifts

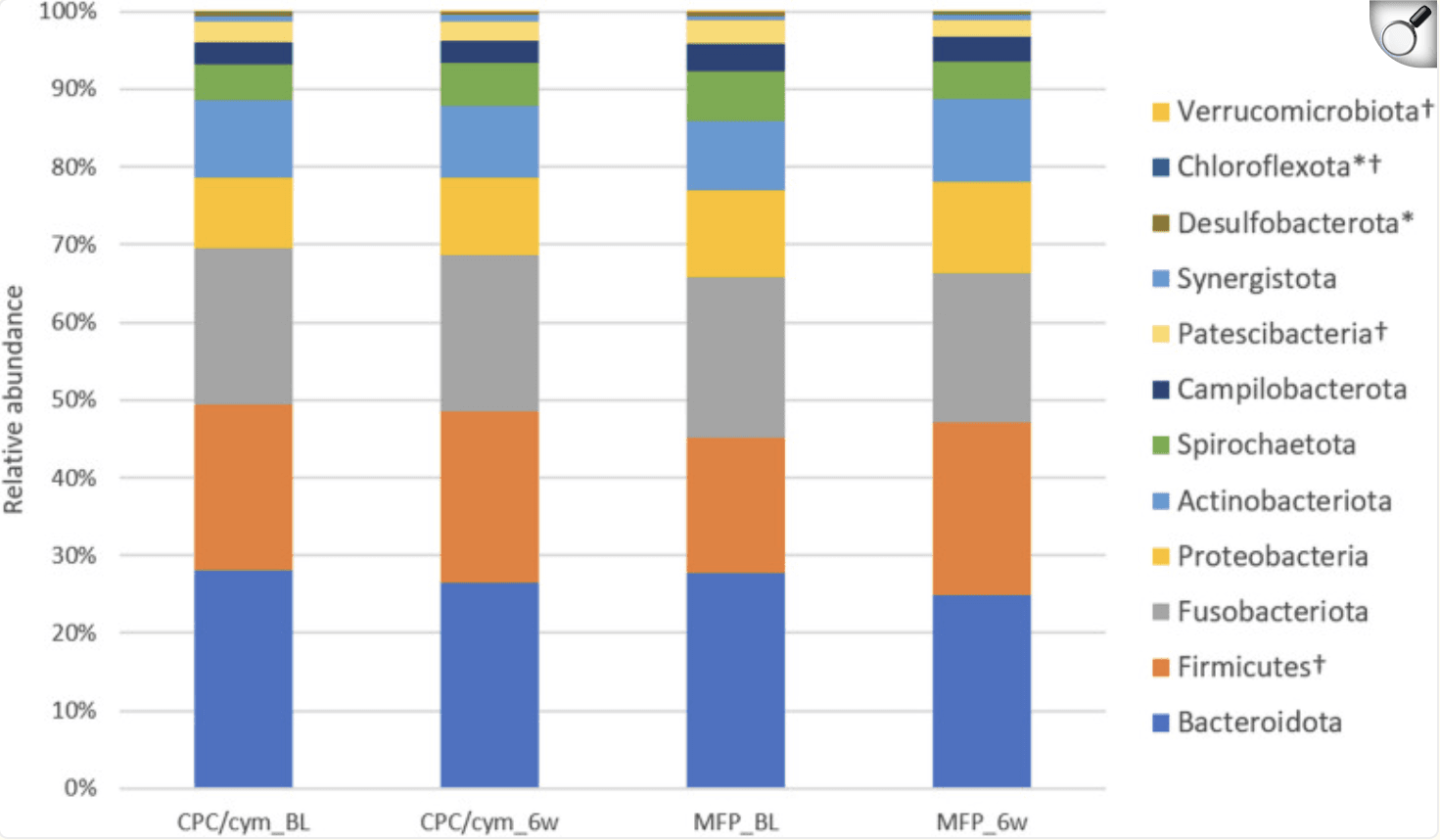

A recent six-week, single-blind randomized trial in Madrid examined whether toothpastes with different active ingredients affect bacteria below the gumline in people with gingivitis. Sixty adults were assigned to brush daily with either a cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) + cymenol toothpaste or a standard sodium monofluorophosphate (MFP, fluoride) toothpaste. Subgingival plaque samples were collected at the start and end, then analyzed via deep sequencing to track shifts in microbiome diversity and composition.

Overall microbial diversity remained stable in both groups—no major dips or spikes. But looking closer at specific bacteria revealed some interesting differences. The CPC + cymenol group saw a significant reduction in Aggregatibacter (p=0.023) and Fusobacterium nucleatum (p=0.030)—two genera linked to gum inflammation. Meanwhile, the fluoride group experienced an increase in certain Firmicutes (p=0.033). Neither toothpaste affected high-risk species like Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, or Tannerella forsythia.

In summary, daily brushing with CPC + cymenol toothpaste appears microbiologically safe and may selectively reduce some problematic bacteria below the gums, without disrupting overall microbial diversity. Fluoride toothpaste showed different, less targeted shifts. These preliminary findings suggest that toothpaste choice could subtly shape oral microbial communities—yet longer and larger trials are needed to confirm real-world impact on gum health.

Changes in the relative abundance of the phyla with an abundance > 0.05%. Treatment groups: CPC/cym, toothpaste with cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) and cymenol (cym), as main active ingredients; MFP, toothpaste with sodium monofluorophosphate (MFP). BL: baseline; 6w: 6 weeks. *: significant intragroup differences in CPC/cym; †: significant intragroup differences in MFP.