Holobiome is a blog series that offers an AI-assisted summary of the latest research articles on human microbiome.

First Steps of the Microbiome: How Birth and Milk Shape Preterm Guts

Preterm babies enter the world with immature intestines and a heightened risk of gut microbiota imbalances that can contribute to serious conditions like necrotizing enterocolitis. To support their fragile development, human milk is often “fortified” to boost nutrition but the choice of fortifier has long puzzled clinicians. This study set out to compare two types of bovine‑based fortifiers rich bovine colostrum versus a traditional mature‑milk formula in 225 preterm infants, analyzing their gut microbes via 16S rRNA sequencing over the first two weeks of fortifier use.

Shortly after birth, the mode of delivery had a striking but fleeting effect: cesarean‑delivered infants tended to have guts dominated by Firmicutes, while those born vaginally showed more Proteobacteria. These differences gradually faded and vanished around one month of life.

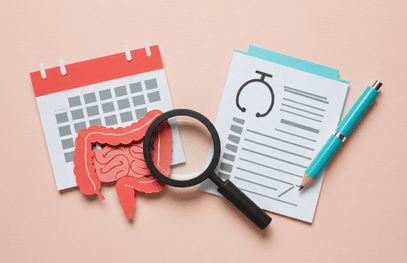

Interestingly, whether an infant received bovine colostrum or the conventional fortifier, subtly affected gut community structure no particular bacterial groups showed strong differences between the two. One subtle twist, however: the colostrum fortifier nudged fecal pH higher, which correlated with a rise in Staphylococcus and Corynebacterium and a dip in Bifidobacterium. Higher levels of Staphylococcus were linked modestly to slower weight gain.

This research suggests that while the choice of fortifier does nudge the infant gut microbiome and its impact is modest in the earliest days. The more vivid microbial shifts relate to how babies are born and those differences tend to smooth out within weeks. Clinically, this means healthcare teams can prioritize nutritional balance when choosing fortifiers, without worrying that one option will drastically shape microbial outcomes.

This glimpse into the earliest establishment of the gut microbiome in preterm infants reminds us how resilient and dynamic these early microbial communities are and how many factors gently shape them, from birth mode to milk feeding strategies.

The gut microbiota is correlated with weight gain and fecal pH. (a) The change of Staphylococcus relative abundance (as determined by the ratio of log10-transformed relative abundance) was negatively correlated with body weight gain (delta body weight Z-scores) from FT0 to FT2 across the fortifier groups after FDR correction. Only 131 infants with samples and body weight data available at all FTs and within three standard deviations (SDs) were included. (b) Fecal pH was significantly higher in the BC group than in the CF group at FT1 (linear regression). *, P < 0.05. (c) Relative abundance of Staphylococcus was positively correlated with fecal pH across FTs (q < 0.01, R = 0.2, n = 538). (d) Relative abundance of Corynebacterium was positively correlated with fecal pH across FTs (q = 0.02, R = 0.2, n = 394). (e) Relative abundance of Bifidobacterium was negatively correlated with fecal pH across three FTs (q < 0.01, R = −0.2, n = 248). Relative abundance of the 15 most abundant genera (central log-ratio transformed) and the pH of fecal samples were correlated by Pearson correlation. P values of all correlations were further adjusted by FDR correction to generate q values.

Celiac Disease, the Gut, and Life After Gluten

When people are newly diagnosed with celiac disease, their guts are pushed out of balance like a river clogged by debris. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed that these patients had more fluid in the small intestine and a slower overall digestive transit compared to healthy folks. Their gut microbes also leaned toward those that break down proteins, think Escherichia coli, Enterobacter, and Peptostreptococcus, a mix that’s not exactly ideal for gut harmony.

After a year on a gluten‑free diet, these digestive dynamics improved a bit but didn’t fully bounce back to normalcy. Interestingly, the gut microbiome shifted too: Bifidobacteria, often seen as the “friendly” gut residents that thrive on fibers like resistant starch and arabinoxylan, dropped in abundance. Meanwhile, Blautia wexlerae a less-talked-about but potentially beneficial microbe were commonly seen.

What’s especially fascinating is how these microbes relate to gut function. Higher levels of Akkermansia muciniphila, known for its role in mucus maintenance, correlated with more sluggish transit and larger colon volumes, while B. wexlerae showed the opposite trend. As B. wexlerae increased after the gluten‑free diet, both transit time and colon size reduced, hinting it might help nudge things back into smoother flow.

In short, adopting a gluten-free diet does help both the gut’s structure and the microbial neighborhood but it doesn’t completely reset the system. Some beneficial bacteria fall away, likely because the diet cuts fiber-rich wheat components. This study shines a light on the delicate interplay between diet, gut mechanics, and our internal ecosystems suggesting that future support for people with celiac disease might involve tailored pre- or probiotic strategies to restore that microbial balance.

Beyond Teeth and Gums: Oral Microbiome Diversity and the Secret to Longer Life

This study takes a deeper look at the oral microbiome and how its diversity might influence the risk of fatality from any cause, including cardiovascular disease. Using data from over 8,000 U.S. adults followed for nearly a decade, researchers examined how the richness of bacteria in the mouth related to long-term health outcomes. They found that people with greater oral microbiome diversity had a lower risk of all-cause mortality, as well as deaths linked to heart disease and other non-cardiovascular conditions

What makes this particularly exciting is that the oral microbiome, unlike the gut, is directly exposed to the external environment and shaped by daily habits like diet, oral hygiene, and smoking. This means that the microbial community in our mouths is highly dynamic and potentially easier to influence. The study also highlighted that the protective link between microbial diversity and lower mortality risk was most evident in Mexican American, non-Hispanic White, and some other ethnic groups, underscoring how cultural and lifestyle differences may shape these outcomes.

Interestingly, common mediators such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and periodontitis did not explain the association. This suggests that oral microbial diversity itself may play a more direct role in systemic health than previously recognized. Mechanisms might include the regulation of blood pressure via nitrate-reducing bacteria or the prevention of chronic inflammation through a more balanced microbial ecosystem.

In essence, this research positions the oral microbiome as more than just a reflection of dental health it may be a powerful predictor of longevity. Maintaining a diverse oral microbial community through healthy habits could become a new frontier in preventive medicine.

Beyond Supplements: Rethinking Gut Health in IBS

Ever feel like your gut has a secret language, whispering clues about how your body really feels? That’s what a recent study set out to explore. Researchers wondered if simple nutritional supplements like resistant starch, pea fibre, chondroitin sulfate, or protein hydrolysate could gently revert the gut into harmony for people living with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Seventy participants with IBS followed a carefully monitored plan. Each day for four weeks, they took one of the supplements or a placebo, while researchers tracked their stool patterns, gut symptoms, quality of life, and even levels of those tiny but mighty short‑chain fatty acids (SCFAs) microbial messengers closely tied to gut health.

By the end of the month, the results were humbling but clear. None of the supplements significantly boosted Bifidobacterium the friendly bacteria that often show up in wellness headlines nor did they uplift SCFA levels more than the placebo. There were subtle improvements in symptoms and mood within each group, but nothing stood out as better than placebo.

What does this mean for anyone rooting for their gut microbes? It’s a reminder that change in our internal ecosystems is neither simple nor quick. While the idea of a one-size-fits-all supplement is appealing, nurturing our gut health often takes more holistic steps like diversifying fiber sources, exploring fermented foods, or fine-tuning stress and sleep. This study shows that real, lasting change for IBS may lie not in quick fixes, but in thoughtful, personalized microbiome care.

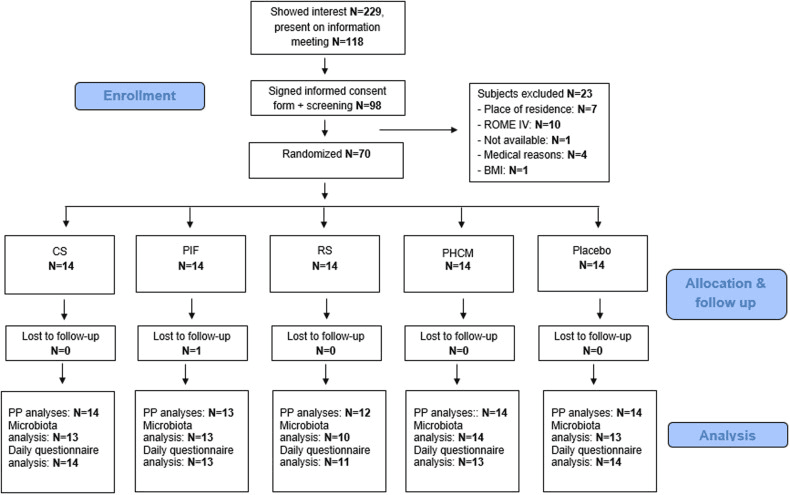

Study participant Flow-chart. Flowchart of study subjects from recruitment and screening to final per protocol (PP) data analyses.

The Night Shift in Your Gut: Microbes that Support Sleep

Ever lie awake, watching the ceiling, thinking about how your gut might be nudging your sleep? A recent study explored this fascinating connection using a pinch of bedtime science: researchers tested whether a probiotic Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BLa80 could help good sleepers drift off more soundly, while gently reshaping the gut community in harmony with the body’s night rhythm.

Over eight weeks, healthy adults received either a daily scoop of BLa80 (10 billion CFU) or a harmless placebo. Sleep was measured using the trusted Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), while gut shifts were tracked using 16S rRNA sequencing. BLa80 brought better sleep: participants reported notably improved PSQI scores compared to the placebo group.

Digging into the gut itself revealed that while overall microbial richness didn’t budge, the balance did. The probiotic lowered the relative levels of potentially troublesome Proteobacteria and increased the number of genera like Bacteroidetes, Fusicatenbacter, and Parabacteroides tiny microbial shifts that might ripple out to bigger health outcomes.

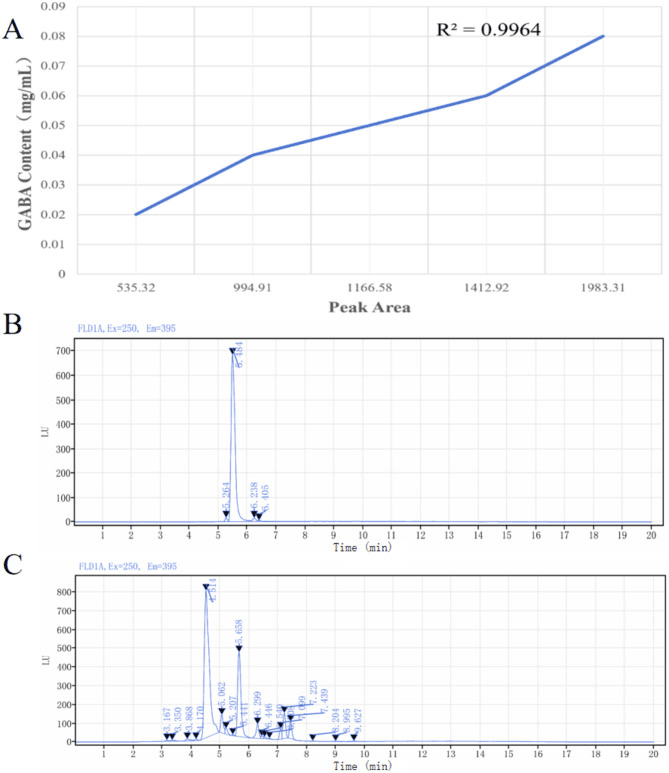

Even more intriguing was the probiotic’s ability to produce GABA, a calming molecule the brain appreciates. And through computational sleuthing (PICRUSt2), scientists saw enhanced metabolic pathways tied to purine and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis processes essential cellular functions with microscopic yet mighty roles.

This study reminds us that a peaceful night’s sleep may be rooted not just in routines or relaxation techniques, but also in the microscopic companionship of our gut microbes. A little nudge toward balance via thoughtful probiotic choices could mean more restful, microbiome-powered slumber.

HPLC determination of BLa80 (A-GABA Standard Curve, B-GABA standard, C-BLa80).

Stay tuned to unravel the latest discoveries on dynamic human-microbe interactions!