The MicroByte Pathogen Series: Yersinia pestis- A Famed Foe

History

Yersinia pestis is well known by most for being one of the most important disease-causing agents in human history. Y. pestis causes the “plague”- outbreaks of which have inspired mythology, superstition, and finally, advancements of medical microbiology. Three major plagues have been documented, with several other historical but unconfirmed mentions. The first plague is known as the ‘Justinian plague’ which broadly went on between the middle 6th to 8th century across the Mediterranean Basin and Europe, named after Justinian I, the Roman emperor under whose rule it began.

The second pandemic, and perhaps the most widely known, raged between the late 1330s and the late 1830s- starting in Central Asia and washing over Europe. The first wave, lasting 7 years, is estimated to have caused the death of between one-fourth and one-third of humanity, and dubbed in modernity ‘The Black Death’. This pandemic had a long-ranging and last impact on the historical and socio-cultural landscape of human history.

The third pandemic is difficult to separate temporally from the second, originating in 1772 in southwestern China, and going on to wreak destruction in all continents, spreading through new steamboat and railway routes. An important and defining event of the third plague occurred in Hong Kong in 1894. Physician Alexandre Yersin and bacteriologist Shibasaburo Kitasato working separately, found the bacteria causative of the plague. Yersin’s superior characterisation earned him the reputation of being the discoverer of this bacteria, and went on to develop an antiserum with his colleagues at the Pasteur Institute, which reduced mortality in affected populations. He named the causative bacteria Pasteurella pestis, and in 1970, it was renamed Yersinia pestis in his honour. It would, however, take many more years for plague to loosen its grip on the world.

Between 1900 and 1909, India suffered millions of deaths due to plague, and numbers lowered when effective measures came into effect. Vietnam in wartime 1965-1975 suffered almost 30,000 cases. Africa followed in the 1980s, and is still currently the continent with the highest burden of plague. In 2005, the plague stopped being a WHO-notifiable disease, an outcome of now more than a hundred of years developing detection methods, protocols, and finding more effective treatments. Plague still remains in the 21st century, but the scale of its effects have been vastly reduced. The 3 most endemic countries for plague are currently Madagascar, Peru, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as reported by the WHO.

Disease Caused

As discussed, the bacterium Yersinia pestis, causes the plague. Multiple forms exist: bubonic, septicemic, and pneumonic. Meningitis and pharyngitis are rarer forms.

Transmission

Y. pestis is transferred by infected blood-sucking fleas, usually to rodents. Thus, bites from infected rodents or directly from infected fleas can spread this pathogen to the bloodstream of humans. Larger carnivores that prey on affected rodents may also contribute to the spread of plague. Pneumonic forms of plague can spread by droplets from respiratory symptoms, and other forms can spread through contact with infected tissue.

Signs and Symptoms

Bubonic plague is the most common form, and is caused by a carrier-flea bite. After 2-8 days of incubation, the patient experiences fever, chills, and fatigue, followed by lymphatic swelling and pain- known as “bubos”. Septicemic plague is similar, but is not associated with bubo development. Pneumonic plague can be a secondary infection from the bubo, or acquired (more rarely) as a primary infection after exposure to another infected person with respiratory symptoms.

Diagnosis

Yersinia pestis infections are diagnosed mainly by isolation and identification of the bacteria in culture. According to the CDC, blood cultures are sensitive and can be used to confirm a plague diagnosis. In the case of high suspicion and a negative culture test, serological assays can be used additionally, which involve the detection of a specific F1 antigen. In field applications, PCR protocols are sometimes used.

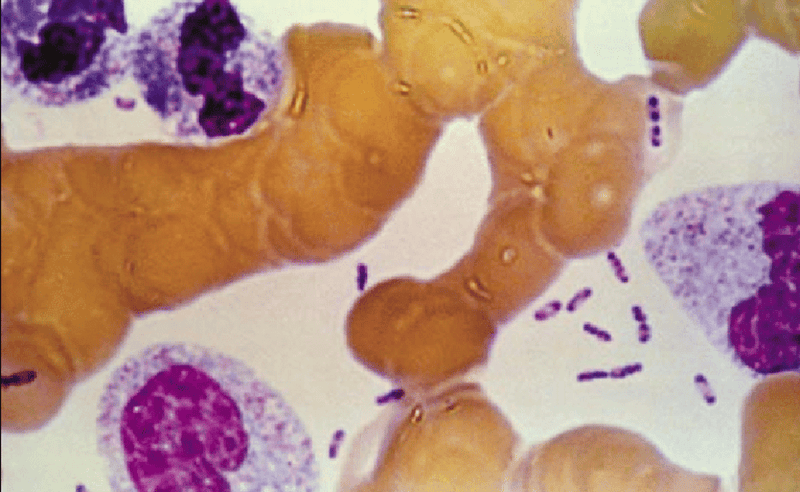

Yersinia pestis has dark ends under Wright’s stain, giving it a characteristic ‘safety pin’ appearance.

Treatment

Modern plague treatments come in the form of antibiotic therapy. This must be done ideally within 24 hours, requiring fast and accurate identification once symptoms start. Streptomycin and gentamicin are commonly used for the treatment of plague in adults and children (with appropriately lowered dosage). Another option is a combination of chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and doxycycline. Based on regulations, treatment plans may vary slightly based on individual countries. Besides antimicrobial treatment for disease clearance, it may also be beneficial to treat severe symptoms of the plague like shock.

Prevention

Since bubonic plague is spread mainly by rodents, the main route for prevention is to avoid contact with rodents, especially in areas of known plague occurrence. Care must be taken to avoid exposure to fleas which carry Y. pestis by using insect repellent, and using appropriate protective gear and clothing when outdoors, and applying insecticides to tents and bedding if any. It is also recommended to avoid handling animal carcasses, and using protective equipment if required. Pneumonic plague can spread from an infected person through droplets, and cases must be isolated with appropriate measures to ensure the infection is not passed on, as well as equipping anyone in contact with the patient with masks, gloves, gowns, and eye coverings. So far, an effective plague vaccine has not been found, though historically vaccines have been used to reduce mortality during certain outbreaks.

Post-exposure prophylaxis, i.e., preventing exposure from progressing to disease, should be given in the form of antibiotics to those who have been exposed to Y. pestis- the bacteria itself, infected fleas or animals, or if they have been in contact with pneumonic plague affected individuals.

On a broader level, care must be taken to avoid providing food and shelter to feral rodents such as waste food, garbage, and piles of material. Pet animals should be regularly checked and treated for fleas. Strategic testing and monitoring of local carnivores (that may acquire the disease after eating smaller animals) and rodent populations can help estimate risks and presence of plague. Upon outbreaks, rat populations must be appropriately culled, and proper control of fleas must be done.

Microbe Profile

Gram status: -ve

Shape: Bacillus/ coccobacillus

Spore formation: No

Motile: No

Optimum temperature: 28-30 degrees Celsius

Optimum pH: 7.4

Taxonomic Classification

Domain: Bacteria

Phylum: Pseudomonadota

Class:Gammaproteobacteria

Order:Enterobacterales

Family: Yersiniaceae

Genus: Yersinia

Species :Yersinia pestis

-Antara Arvind

References

Barbieri, R., Signoli, M., Chevé, D., Costedoat, C., Tzortzis, S., Aboudharam, G., Raoult, D., & Drancourt, M. (2020). Yersinia pestis: the Natural History of Plague. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 34(1). https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00044-19

Butler, T. (2014). Plague history: Yersin’s discovery of the causative bacterium in 1894 enabled, in the subsequent century, scientific progress in understanding the disease and the development of treatments and vaccines. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 20(3), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12540

Clinical testing and diagnosis for plague. (2024, May 15). Plague. https://www.cdc.gov/plague/hcp/diagnosis-testing/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/plague/healthcare/clinicians.html

Dillard, R. L., & Juergens, A. L. (2023, August 7). Plague. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549855/

Ditchburn, J., & Hodgkins, R. (2019). Yersinia pestis, a problem of the past and a re-emerging threat. Biosafety and Health, 1(2), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsheal.2019.09.001

Epidemic and Pandemic Preparedness and Prevention (EPP). (2024, September 25). Manual for plague surveillance, diagnosis, prevention and control. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090422

Nyenke, C. U., Esiere, R. K., Nnokam, B. A., & Nwalozie, R. (2023). Plague: symptoms, transmission, diagnosis, prevention and treatment. South Asian Journal of Research in Microbiology, 16(1), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.9734/sajrm/2023/v16i1297

World Health Organization: WHO. (2019, November 1). Plague. https://www.who.int/health-topics/plague#tab=tab_1

Yang, R. (2017a). Plague: recognition, treatment, and prevention. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 56(1). https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01519-17

Yang, R. (2017b). Plague: recognition, treatment, and prevention. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 56(1). https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01519-17

Yersin, B. W. A. (2010). Etymologia: Yersinia. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 16(3), 496. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1603.et1603