The MicroByte Pathogen Series: Understanding Staphylococcus aureus— Transmission, Disease, and Prevention

History

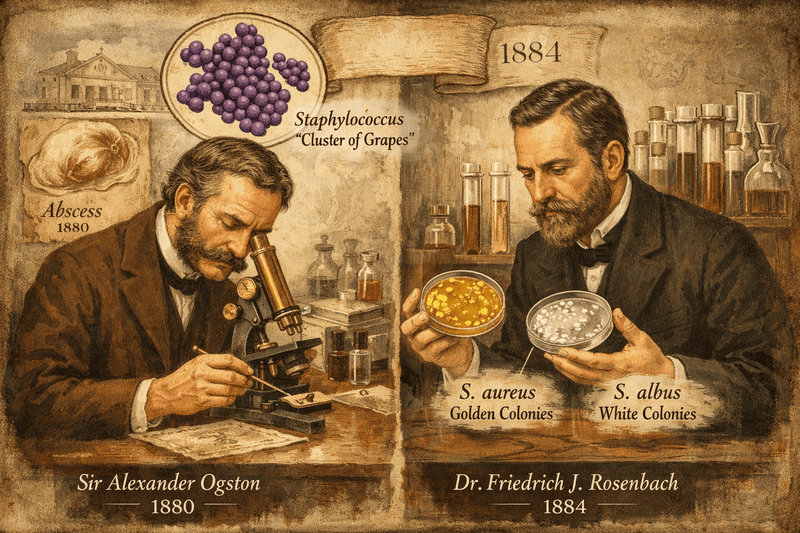

The story of Staphylococcus aureus is one of scientific discovery intertwined with an ongoing battle between medicine and microbial evolution. It began in 1880, when Scottish surgeon Sir Alexander Ogston identified the bacterium as the main cause of acute abscesses and what was then known as “blood poisoning.” While examining pus from a knee joint abscess, he noticed distinctive grape-like clusters of bacteria — a feature that inspired the name Staphylococcus, meaning “cluster of grapes.” A few years later, in 1884, German physician Friedrich Julius Rosenbach successfully isolated the organism in pure culture. He distinguished two types based on their colony color: S. aureus, which forms golden colonies, and S. albus — now called S. epidermidis — which produces white colonies.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenic success of Staphylococcus aureus lies in its remarkable arsenal of toxins and virulence factors, which enable it to survive, spread, and evade immune defenses within the human body. Infection begins with colonization, driven by specialized surface proteins called Microbial Surface Components Recognizing Adhesive Matrix Molecules (MSCRAMMs), which help the bacterium attach to host tissues. Fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBPA and FnBPB) anchor the organism to fibronectin and fibrinogen and allow it to invade epithelial cells, providing protection from immune attack. Clumping factors (ClfA and ClfB) bind fibrinogen and promote clot formation, contributing to the vegetations seen in staphylococcal endocarditis, while Protein A (Spa) binds the Fc portion of IgG antibodies, blocking complement activation and preventing effective opsonization. Once established, the bacterium releases potent toxins that damage tissues and disrupt immune responses. Alpha-hemolysin forms pores in host cell membranes by activating the ADAM10 receptor, breaking down epithelial junctions and enabling bacterial spread. Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), commonly associated with highly virulent community strains, destroys neutrophils and leads to severe necrotic skin infections and pneumonia. Superantigens such as TSST-1 and enterotoxins bypass normal antigen presentation and trigger massive, non-specific T-cell activation, causing a cytokine storm that can result in toxic shock syndrome. In addition, S. aureus produces enzymes that facilitate tissue invasion and immune evasion: coagulase forms protective fibrin barriers around bacterial clusters, hyaluronidase breaks down connective tissue to promote spread, staphylokinase dissolves clots to release bacteria into the bloodstream, and thermonuclease (DNase) helps the pathogen escape neutrophil extracellular traps. Together, these coordinated mechanisms allow S. aureus to colonize, damage, and disseminate efficiently within the host.

Transmission

Transmission of Staphylococcus aureus occurs primarily through direct contact and silent colonization, allowing it to spread efficiently in both community and healthcare settings. Many people carry the bacterium harmlessly on their skin or in their noses particularly in the anterior nasal passages, which serve as its most stable reservoir but it can also colonize other body sites such as the skin, throat, and perineal region. These asymptomatic carriers are the main source of transmission, often spreading the organism without realizing it. The bacterium spreads most commonly through skin-to-skin contact, contaminated hands of healthcare workers, shared personal items, and frequently touched surfaces where it can survive for extended periods. In hospitals, close contact among patients and staff, environmental contamination, invasive procedures, surgical wounds, and medical devices increase the risk of transfer and allow colonizing bacteria to enter deeper tissues and cause infection. In community settings, factors such as crowding, poor hygiene, and skin injuries promote spread, especially in places like gyms, schools, and households, while certain strains can also circulate between humans and animals, contributing to livestock-associated transmission. Overall, the persistence of S. aureus on the body and in the environment, combined with widespread asymptomatic carriage and repeated human contact, makes controlling its transmission especially challenging and highlights the importance of strict hygiene, infection control, and carrier identification.

Signs and Symptoms

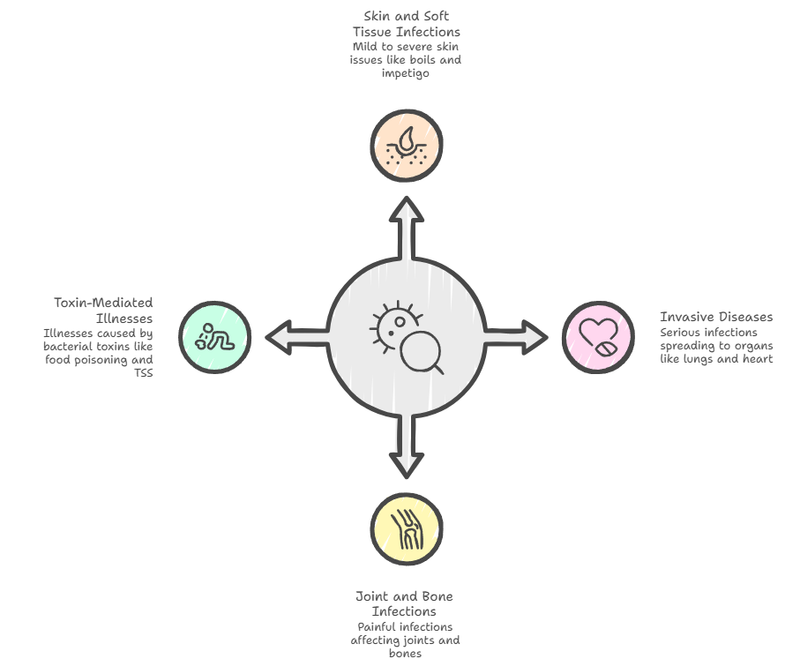

Staphylococcus aureus infections can produce a wide range of signs and symptoms, from mild skin problems to severe, life-threatening illness. The most common manifestations are skin and soft tissue infections, often appearing as “spider bite-like” lesions. These include folliculitis, which causes itchy, pus-filled bumps in hair follicles; furuncles and carbuncles, which are deeper, painful boils that may spread into the bloodstream if untreated; impetigo, a highly contagious infection marked by honey-colored crusted sores; and cellulitis, a deeper skin infection causing redness, warmth, swelling, and tenderness, usually in the legs. If the bacteria enter the bloodstream, they can cause serious invasive disease such as bacteremia and sepsis, often spreading to other organs and leading to pneumonia, bone infections, or heart valve infection (infective endocarditis), which can rapidly damage the heart. The organism can also infect joints and bones, causing severe pain, swelling, and fever. In addition, some illnesses are caused by toxins produced by the bacteria rather than direct infection, including food poisoning with sudden nausea and vomiting after eating contaminated food, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in children where the skin peels like a burn, and toxic shock syndrome, a rapidly progressing condition marked by high fever, low blood pressure, and multi-organ involvement.

Diagnosis

The accurate diagnosis of Staphylococcus aureus infection relies on a combination of traditional microbiological methods and modern rapid diagnostic techniques. The gold standard remains the culture of clinical specimens such as pus, blood, or sputum, followed by laboratory identification. On Gram staining, the organism appears as Gram-positive cocci arranged in grape-like clusters. A catalase test helps distinguish Staphylococcus species from Streptococcus, as staphylococci produce bubbles when exposed to hydrogen peroxide. The coagulase test is the key confirmatory test for S. aureus, detecting the enzyme that causes plasma to clot within several hours. Because severe infections require rapid diagnosis, molecular methods are widely used: PCR can quickly detect S. aureus and resistance genes such as mecA directly from clinical samples, while fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) identifies the organism in blood cultures using fluorescent DNA probes. Additionally, MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry has transformed clinical microbiology by identifying bacteria based on their protein profiles, allowing highly accurate species identification within minutes after colony growth. Together, these methods enable fast and reliable detection to guide timely treatment.

Treatment

Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections depends on the severity and site of disease, as well as whether the strain is antibiotic-resistant, particularly methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Mild skin and soft tissue infections are often managed with drainage and targeted oral antibiotics, while serious invasive infections such as bacteremia, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, or pneumonia require prompt intravenous therapy and sometimes prolonged treatment. Effective management always includes source control such as draining abscesses or removing infected medical devices alongside antimicrobial therapy. For methicillin-susceptible strains (MSSA), beta-lactamase-stable penicillins like cloxacillin or oxacillin are typically preferred because of their strong bactericidal activity. However, due to the high prevalence of MRSA, especially in severe infections, glycopeptides such as vancomycin are commonly used as empirical therapy in critically ill patients, though they require intravenous administration and careful monitoring to prevent kidney toxicity. Other important options include linezolid, which is highly effective for MRSA pneumonia and skin infections and has excellent oral absorption, and daptomycin, which is used for serious bloodstream infections and endocarditis but cannot be used for pneumonia because it becomes inactive in the lungs. Treatment can be challenging because the bacterium can form protective biofilms on tissues and medical devices and survive inside host cells, leading to persistent or recurrent infections that may require surgical intervention. Emerging therapies including antibody-antibiotic conjugates, anti-biofilm approaches, bacteriophage therapy, and immunomodulatory strategies.

Prevention

Preventing the spread of Staphylococcus aureus, especially in healthcare settings, relies on strict infection-control practices such as proper hand hygiene, routine environmental cleaning, and targeted decolonization of individuals at high risk of infection or transmission. Decolonization focuses on eliminating the bacterium from its main reservoir — particularly the nasal passages — in people who carry it without symptoms. A commonly used regimen involves applying 2% nasal mupirocin ointment to both nostrils twice daily for 5 to 10 days, combined with daily full-body washing using 4% chlorhexidine gluconate. When used before high-risk surgeries such as cardiothoracic or orthopedic procedures, this approach — typically completed about 48 hours before the operation — can significantly reduce postoperative infections. However, routine decolonization of all asymptomatic carriers is generally not recommended, as widespread use can promote antibiotic resistance, particularly to mupirocin, without providing clear benefit in low-risk populations. Overall, effective prevention depends on good hygiene practices, careful screening of high-risk individuals, and responsible use of decolonization strategies.

Microbial Profile

Shape: Spherical

Gram Nature: Gram positive

Spore Formation: No spore formation

Oxygen Requirement: Facultative anaerobes

Optimal Temperature: 30℃ to 37℃

Optimal pH: 6.0- 7.5

Laboratory culture media: Mannitol Salt Agar

Taxonomic Classification

Domain: Bacteria

Kingdom: Bacillati

Phylum: Bacillota

Class: Bacilli

Order: Bacillales

Family: Staphylococcaceae

Genus:Staphylococcus

Species: Staphylococcus aureus

-Varsha V

Also Read: The MicroByte Pathogen Series: Bordetella pertussis- Bacterium Behind Whooping Cough

Reference

Myles, I. A., & Datta, S. K. (2012). Staphylococcus aureus: an introduction. Seminars in immunopathology, 34(2), 181–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-011-0301-9

Cheung, G. Y. C., Bae, J. S., & Otto, M. (2021). Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence, 12(1), 547–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.1878688

Touaitia, R., Mairi, A., Ibrahim, N. A., Basher, N. S., Idres, T., & Touati, A. (2025). Staphylococcus aureus: A Review of the Pathogenesis and Virulence Mechanisms. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland), 14(5), 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14050470

Knox, J., Uhlemann, A. C., & Lowy, F. D. (2015). Staphylococcus aureus infections: transmission within households and the community. Trends in microbiology, 23(7), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.007

Solberg, C. O. (2000). Spread of Staphylococcus aureus in Hospitals: Causes and Prevention. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 32(6), 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/003655400459478

Karmakar, A., Dua, P., & Ghosh, C. (2016). Biochemical and Molecular Analysis of Staphylococcus aureus Clinical Isolates from Hospitalized Patients. The Canadian journal of infectious diseases & medical microbiology = Journal canadien des maladies infectieuses et de la microbiologie medicale, 2016, 9041636. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9041636

Qing Wu, Yan Li, Huixia Hu, Ming Wang, Zegang Wu, Wanzhou Xu, Rapid Identification of Staphylococcus aureus: FISH Versus PCR Methods, Laboratory Medicine, Volume 43, Issue 6, November 2012, Pages 276–280, https://doi.org/10.1309/LMDPO72QOWXO9WZO

Wolk, D. M., Blyn, L. B., Hall, T. A., Sampath, R., Ranken, R., Ivy, C., Melton, R., Matthews, H., White, N., Li, F., Harpin, V., Ecker, D. J., Limbago, B., McDougal, L. K., Wysocki, V. H., Cai, M., & Carroll, K. C. (2009). Pathogen profiling: rapid molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus by PCR/electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry and correlation with phenotype. Journal of clinical microbiology, 47(10), 3129–3137. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00709-09

David, M. Z., & Daum, R. S. (2017). Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus Infections. Current topics in microbiology and immunology, 409, 325–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/82_2017_42

Brown, N. M., Goodman, A. L., Horner, C., Jenkins, A., & Brown, E. M. (2021). Treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): updated guidelines from the UK. JAC-antimicrobial resistance, 3(1), dlaa114. https://doi.org/10.1093/jacamr/dlaa114

Popovich, K. J., Aureden, K., Ham, D. C., Harris, A. D., Hessels, A. J., Huang, S. S., Maragakis, L. L., Milstone, A. M., Moody, J., Yokoe, D., & Calfee, D. P. (2023). SHEA/IDSA/APIC Practice Recommendation: Strategies to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission and infection in acute-care hospitals: 2022 Update. Infection control and hospital epidemiology, 44(7), 1039–1067. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2023.102