The MicroByte Pathogen Series : Clostridum botulinum- Botulinum Paradox

History

The first outbreak of botulism was reported in 1793 following the consumption of sausages contaminated with Clostridium botulinum in Wildbad, Germany. In 1822, Justinus Kerner provided the first comprehensive description of the symptoms of botulism. Later, in 1895, the Belgian microbiologist Émile van Ermengem successfully isolated C. botulinum from ham after an outbreak in Ellezelles, Belgium. In the early 20th century, researchers discovered that a toxin produced by Clostridium botulinum, known as botulinum toxin, was responsible for the severe symptoms of the disease. Subsequently, multiple strains of C. botulinum were identified that produce different types of botulinum toxin, designated A through G. Among these, toxin types A, B, E, and F are responsible for human illness.

Clostridium botulinum, showing Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacilli.

Transmission

Clostridium botulinum is transmitted through the consumption of spiced, smoked, vacuum-packed, and canned alkaline foods. Honey acts as a natural reservoir for Clostridium botulinum spores and is a major cause of infant botulism.

Apart from foodborne intoxication, during the early 2000s there was a surge in botulism cases among injection drug users in the U.S., the U.K and Germany due to contamination of black tar heroin. This highlighted the high risk of infection through wounds and practices such as skin popping.

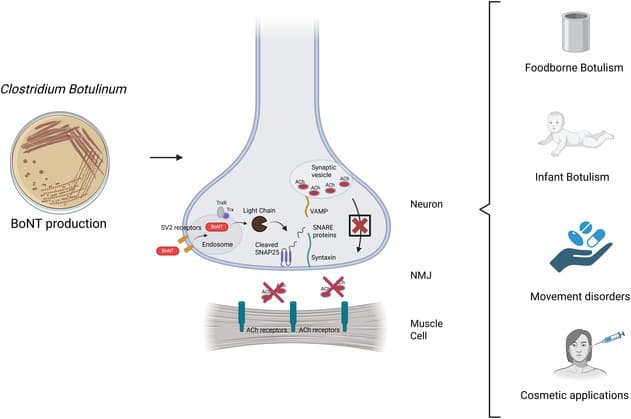

Graphical overview of Clostridium botulinum, depicting modes of transmission, key mechanisms of pathogenesis, and therapeutic and cosmetic applications of botulinum toxin.

Pathogenesis

When Clostridium botulinum spores are ingested, inhaled, or enter the body through wounds such as skin popping, they can germinate in the digestive tract, bronchioles, or necrotised tissues. Once the bacterium begins to colonise these sites, it produces botulinum toxin, which is released into the circulation. When this toxin encounters motor neurons—nerve cells responsible for relaying signals from the brain and spinal cord to the muscles—it binds to and enters the neuron. Inside the neuron, the toxin cleaves a protein called SNARE, thereby inhibiting the release of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter responsible for muscle contraction, ultimately resulting in paralysis.

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of botulism typically begin 18 to 24 hours after the entry of Clostridium botulinum or its spores into the body. These symptoms include visual disturbances, difficulty in swallowing, speech impairment, and progressive paralysis, which can eventually lead to death, most commonly due to respiratory paralysis and cardiac failure. In infant botulism, affected infants also develop signs of paralysis, including poor feeding and generalized weakness.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of botulism is based primarily on clinical symptoms. Detection of Clostridium botulinum in faeces, intestinal contents, or wound swabs can support the diagnosis. In infants, detection of C. botulinum in faeces or intestinal contents through culturing usually confirms the disease. However, culture-based techniques are not always reliable, as they do not specifically identify virulent, toxin-producing strains of C. botulinum and can therefore be misleading.

Traditionally, laboratory diagnosis of botulism relied on the mouse lethality assay, in which stool or serum samples from patients were injected into live mice, and the onset of symptoms or death was observed and compared with control (untreated) mice. This assay also allowed identification of the toxin type and the virulent strains. However, this method is no longer routinely practiced, as it is slow for diagnostic purposes and raises ethical concerns.

Modern diagnostic methods include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR is used to detect C. botulinum strains that carry genes encoding the virulent botulinum toxin.

Treatment

Antitoxin therapy is the primary treatment for botulism and is available in two forms.

- Heptavalent equine serum antitoxin: This preparation contains antibodies against botulinum toxin types A through G and is typically administered to patients older than one year.

- Human-derived antibodies (immunoglobulins): These are used for patients younger than one year.

In cases of infant botulism, antibiotics are generally not prescribed, except in wound botulism, as antibiotic treatment can worsen the condition. This is because antibiotics can cause bacterial lysis, leading to increased release of botulinum toxin. In wound botulism, antibiotic therapy is indicated following antitoxin administration. Tetanus vaccination may also be required in such cases. Antitoxin therapy cannot reverse existing paralysis, however, it helps prevent disease progression by irreversibly binding to circulating toxin.

Prevention

To prevent botulism, it is important to follow appropriate food-handling and storage practices. Particular attention should be paid to hygiene while preparing home-cooked, canned, low-acid foods. Canned foods, such as home-preserved tomatoes, should be boiled for at least 5 to 10 minutes, which inactivates the toxin and kills vegetative bacteria, though it does not destroy the spores. Clostridiumbotulinum spores can be destroyed through pressure canning at 15 to 20 lb/in², at a temperature of 121 °C for at least 20 minutes. Consumption of expired canned products or food from damaged or defective cans should be avoided. Cooking utensils should be properly washed, maintained, and stored in a hygienic manner. If contamination is suspected, it is recommended to boil utensils and disinfect them with bleach to inactivate any toxin. To prevent infant botulism, honey should not be given to infants.

Also Read: The MicroByte Pathogen Series: Yersinia pestis- A Famed Foe

Interesting Fact

Journey of Botulinum Toxin Beyond Lethality

Toxins produced by Clostridium botulinum are among the most potent substances known. A very small dose, approximately 1–2 μg/kg, can be life-threatening. However, despite its extreme toxicity, botulinum toxin has a wide range of applications, from the cosmetic industry to therapeutic medicine.

Commonly known as “BOTOX,” botulinum toxin type A is injected into specific facial muscles, where it temporarily inhibits the release of acetylcholine and promotes muscle relaxation. This effect smoothens the skin and reduces the appearance of wrinkles and fine lines. The effects of this treatment typically last for 3 to 6 months.

This property of botulinum toxin is also exploited in the treatment of various medical conditions, including focal movement disorders of the face and neck, muscle spasms, and smooth muscle disorders.

Microbe profile

Shape : Rod shaped

Gram nature : Gram positive

Spore formation : Yes

Oxygen requirement : Anaerobe

Optimal temperature :35-37°C

Optimal pH : 6-7

Taxonomic classification

Domain : Bacteria

Kingdom : Bacillati

Phylum : Bacillota

Class : Clostridia

Order : Eubacteriales

Family :Clostridiaceae

Genus :Clostridium

Species : C. botulinum

-Khushi.C

References

Jeffery IA, Nguyen AD, Karim S. Botulism. [Updated 2024 Nov 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459273/

Merialdi, G., Ramini, M., Parolari, G., Barbuti, S., Frustoli, M. A., Taddei, R., Pongolini, S., Ardigò, P., & Cozzolino, P. (2016). Study on Potential Clostridium Botulinum Growth and Toxin Production in Parma Ham. Italian journal of food safety, 5(2), 5564. https://doi.org/10.4081/ijfs.2016.5564

Botulism prevention. (2024, May 6). Botulism. https://www.cdc.gov/botulism/prevention/index.html

Lindström, M., & Korkeala, H. (2006). Laboratory diagnostics of botulism. Clinical microbiology reviews, 19(2), 298–314. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.19.2.298-314.2006

Monash, A., Tam, J., Rosen, O., & Soreq, H. (2025). Botulinum Neurotoxins: History, Mechanism, and Applications. A Narrative Review. Journal of neurochemistry, 169(8), e70187. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.70187

Dhaked, R. K., Singh, M. K., Singh, P., & Gupta, P. (2010). Botulinum toxin: bioweapon & magic drug. The Indian journal of medical research, 132(5), 489–503.

Brooks, G., Carroll, K. C., Butel, J., & Morse, S. (2012). Jawetz Melnick&Adelbergs Medical Microbiology 26/E. McGraw Hill Professional.