The Microbyte Series: Meet the Starch-Lover: Lactobacillus amylovorus

History

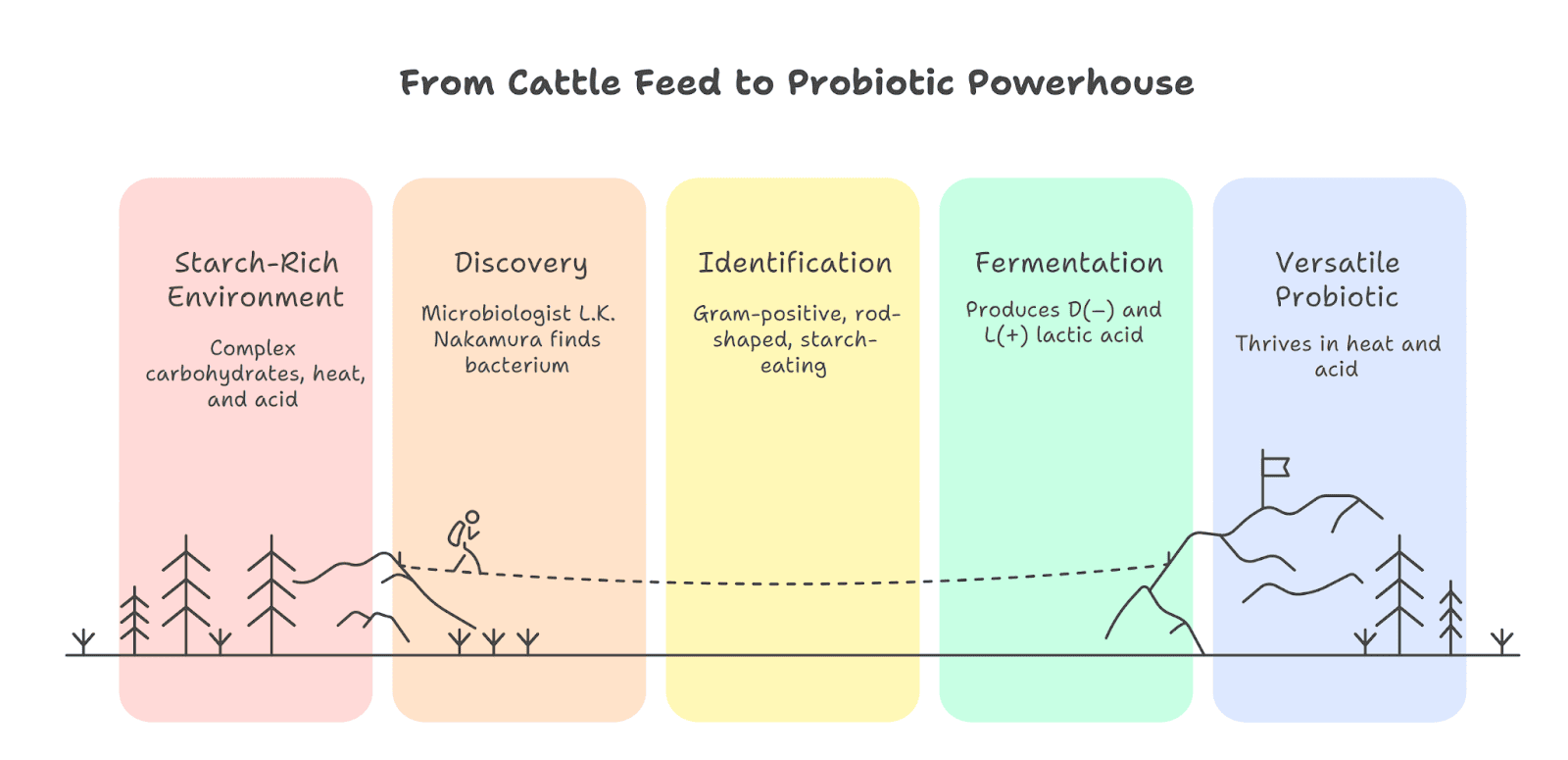

Not all probiotics are born in a yogurt cup; some emerge from much humbler beginnings. Lactobacillus amylovorus was first discovered in 1981 by microbiologist L.K. Nakamura, deep within fermenting cattle feed. This humble, starch-rich environment revealed a bacterium unlike its relatives: one that could devour complex carbohydrates and thrive in heat and acid. Its very name tells the story “amylovorus” means “starch-eating.”

For years, L. amylovorus was considered part of the Lactobacillus acidophilus group, a family of gut-friendly species adapted to animals. Later, genetic studies clarified its unique identity. Interestingly, a species once named Lactobacillus sobrius was later found to be genetically identical, merging back into L. amylovorus.

In 2020, when scientists reorganized over 200 Lactobacillus species into new genera, L. amylovorus held its ground in the core Lactobacillus genus. And in 2024, researchers proposed new subspecies amylovorus and animalis highlighting its evolutionary journey from soil and silage to the animal gut.

Health benefits

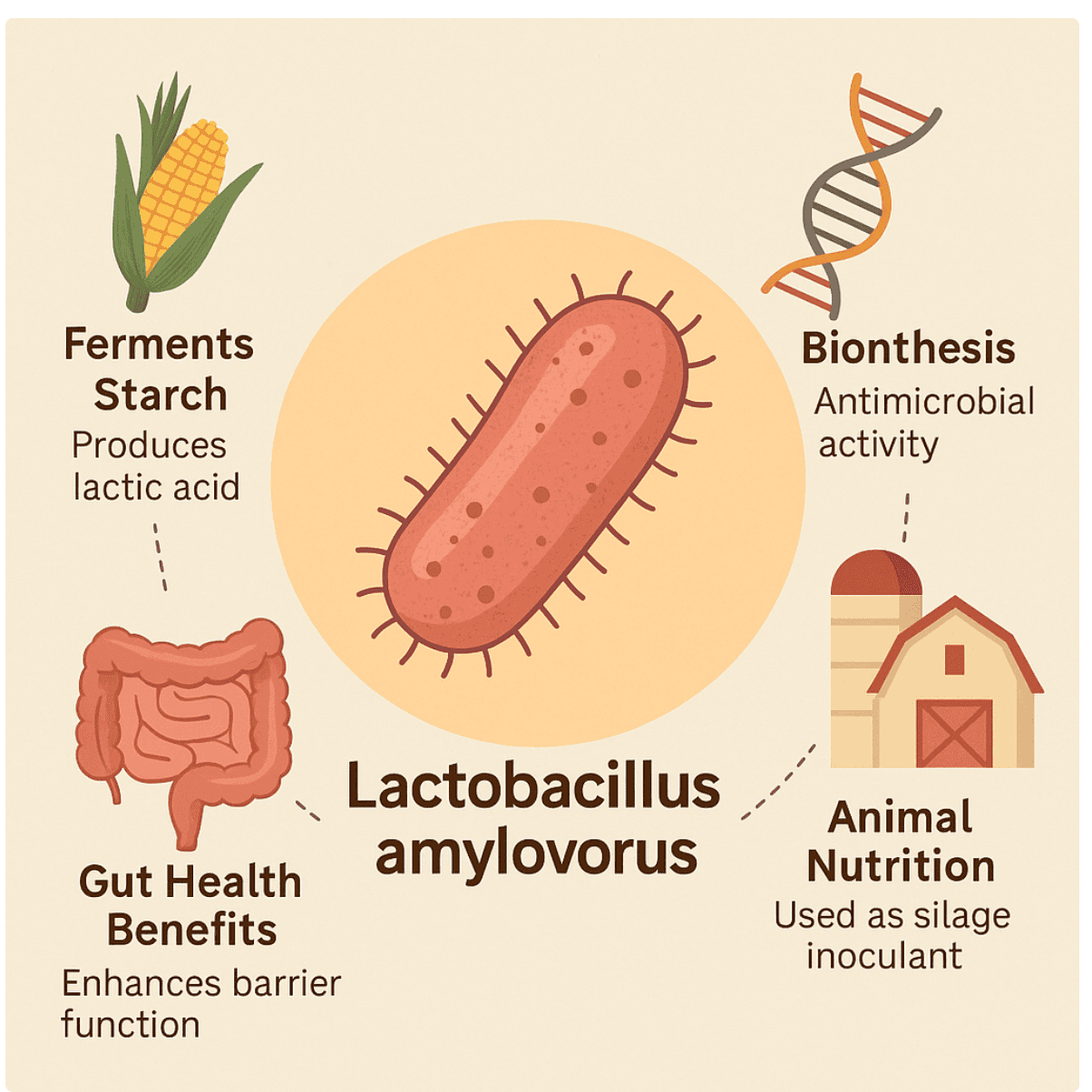

Animal studies show that L. amylovorus isn’t just a bystander in the gut, it's an active contributor to intestinal health. In piglets with growth challenges, supplementation improved gut structure, increasing villus height and strengthening intestinal tight junctions through upregulation of Claudin-1.

Functionally, it helps the gut digest lactose and boosts glucose uptake by increasing GLUT2 expression, essentially teaching the gut to absorb nutrients more efficiently. These effects translate into measurable outcomes: better growth, improved digestion, and stronger barrier protection.

Its S-layer proteins also help it compete for space, preventing pathogens like E. coli and Salmonella from attaching. At the immune level, L. amylovorus may help balance inflammation by decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (like TNF-α and IL-1β) and increasing anti-inflammatory signals (like IL-10). This fine-tuned immunomodulation shows why it’s a promising candidate for gut health support not only in animals but potentially in humans as well.

Applications

In the agricultural world, L. amylovorus is a trusted ally. It’s used as a silage inoculant, a microbial starter that rapidly acidifies forage and locks in nutrients, creating stable, pathogen-free animal feed. Its ability to dominate in acidic, carbohydrate-rich environments makes it ideal for this role.

In biotechnology, it’s gaining recognition as a biofactory. Under optimized fermentation, strains like DCE 471 can produce large quantities of helveticin J, a natural antimicrobial peptide that could replace chemical preservatives in food. Its ability to synthesize B-vitamins also positions it for use in functional foods and supplements, potentially enriching human diets naturally.

Why It Matters: Beyond a Typical Probiotic

The story of Lactobacillus amylovorus reminds us that science often hides its best discoveries in unexpected places, in this case, a pile of fermenting corn waste. Over four decades of research have turned this once-obscure bacterium into a promising probiotic with dual power: improving animal health while supporting sustainable fermentation industries.

Its unique combination of acid and bile tolerance, vitamin biosynthesis, adhesion, and antimicrobial activity sets it apart from standard probiotics. It’s not just a microbe that survives the gut; it’s one that reshapes it, promoting resilience, nutrient efficiency, and microbial balance.

As research continues, the future may see L. amylovorus added to specialized probiotic formulations, next-generation feed additives, or even personalized gut-health therapies. From silage tanks to intestinal walls, this tiny “starch-eater” has proven that adaptability and intelligence aren’t limited to large organisms; they thrive at the microscopic scale too.

Microbe Profiles

Shape: Rod Shape

Gram nature: Gram Positive

Spore formation: No

Biofilm formation: Yes

Oxygen requirement :

Optimal temperature: 45–48 °C

Optimal pH: 3

Nutrient usage: Ferments simple sugars like glucose, lactose

Taxonomic Classification

Domain: Bacteria

Kingdom: Bacillati

Phylum: Bacillota

Class:Bacilli

Order: Lactobacillales

Family:Lactobacillaceae

Genus:Lactobacillus

Species: Lactobacillus amylovorus

-Neha Rao

References

Dewi, G., & Kollanoor Johny, A. (2022). Lactobacillus in food animal production—a forerunner for clean label prospects in animal-derived products. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 6, 831195.

Latif, A., Shehzad, A., Niazi, S., Zahid, A., Ashraf, W., Iqbal, M. W., Rehman, A., Riaz, T., Aadil, R. M., Khan, I. M., Özogul, F., Rocha, J. M., Esatbeyoglu, T., & Korma, S. A. (2023). Probiotics: mechanism of action, health benefits and their application in food industries. Frontiers in microbiology, 14, 1216674. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1216674

Kant, R., Paulin, L., Alatalo, E., de Vos, W. M., & Palva, A. (2011). Genome sequence of Lactobacillus amylovorus GRL1118, isolated from pig ileum. Journal of bacteriology, 193(12), 3147–3148. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00423-11

Walter J. (2008). Ecological role of lactobacilli in the gastrointestinal tract: implications for fundamental and biomedical research. Applied and environmental microbiology, 74(16), 4985–4996. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00753-08

Park, S., Kim, J. A., Jang, H. J., Kim, D. H., & Kim, Y. (2023). Complete genome sequence of functional probiotic candidate Lactobacillus amylovorus CACC736. Journal of animal science and technology, 65(2), 473–477. https://doi.org/10.5187/jast.2022.e85