The MicroByte Pathogen Series: Bordetella pertussis- Bacterium Behind Whooping Cough

History

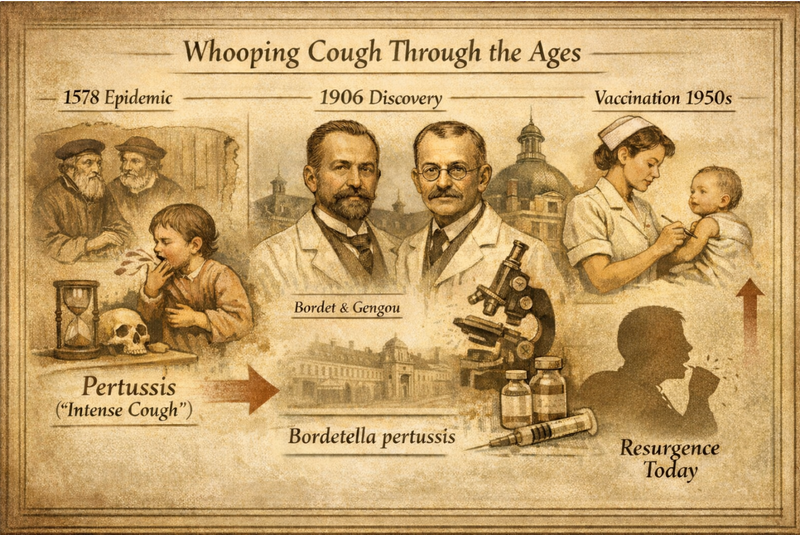

Whooping cough has been recognized for centuries, long before its bacterial cause was understood. The first clear medical description dates back to a 1578 epidemic in Paris, where physicians documented a mysterious illness marked by relentless, spasmodic coughing. The disease came to be known as pertussis, derived from the Latin per (intense) and tussis (cough), a name that captures its most striking symptom.

The true cause of pertussis remained unknown until the early 20th century. In 1906, Belgian bacteriologist Jules Bordet and his colleague Octave Gengou successfully isolated the responsible organism while working at the Pasteur Institute. Their discovery was a turning point, made possible by the development of a specialized culture medium capable of supporting this fastidious bacterium. In recognition of Bordet’s work, the organism was later named Bordetella pertussis. Earlier in its scientific history, it was referred to as the “Bordet–Gengou bacillus” and was even misclassified as Haemophilus pertussis before its unique characteristics warranted placement in a new genus.

The introduction of widespread vaccination in the mid-20th century led to a dramatic decline in pertussis cases worldwide. However, the disease has never disappeared entirely, and periodic resurgences continue to occur—driven by waning immunity and ongoing bacterial adaptation.

Pathogenesis

Bordetella pertussis is a strictly human pathogen with a strong preference for the respiratory tract. Infection begins when inhaled bacteria attach firmly to the ciliated epithelial cells lining the upper airways. This attachment is mediated by surface adhesins such as filamentous hemagglutinin, pertactin, and fimbriae, which allow the organism to resist mechanical clearance by mucus and airflow.

Unlike many bacterial pathogens, B. pertussis does not invade deeper tissues or enter the bloodstream. Instead, disease results from the release of a potent arsenal of toxins. Pertussis toxin disrupts immune cell signaling and causes marked lymphocytosis, while adenylate cyclase toxin disables phagocytic cells by overwhelming them with cyclic AMP. Tracheal cytotoxin damages and kills ciliated epithelial cells, effectively shutting down the muco-ciliary escalator that normally clears debris from the airways. Together, these effects leave mucus trapped in the bronchi, triggering the intense coughing fits that define the disease.

The bacterium’s lipopolysaccharide cell wall also contributes to local inflammation. In essence, pertussis is a toxin-mediated illness: the bacteria cling to the airway surface while their secreted products drive tissue injury, immune dysfunction, and prolonged coughing.

Transmission

Pertussis spreads easily from person to person through respiratory droplets released during coughing or sneezing. Close contact greatly increases the risk of transmission, and attack rates among susceptible household contacts can reach 80–100% in unvaccinated populations. Humans are the only natural reservoir for B. pertussis; there are no animal hosts or insect vectors involved.

After an incubation period typically lasting 5–10 days (but occasionally up to three weeks), infected individuals develop symptoms and become most contagious during the early, cold-like phase of illness. Infectiousness gradually declines thereafter but can persist for several weeks in untreated cases. Antibiotic therapy shortens this period, with patients generally considered non-infectious after five days of appropriate treatment. Because pertussis spreads so efficiently, it often causes community outbreaks, particularly in settings where immunity is low or has waned.

Signs and Symptoms

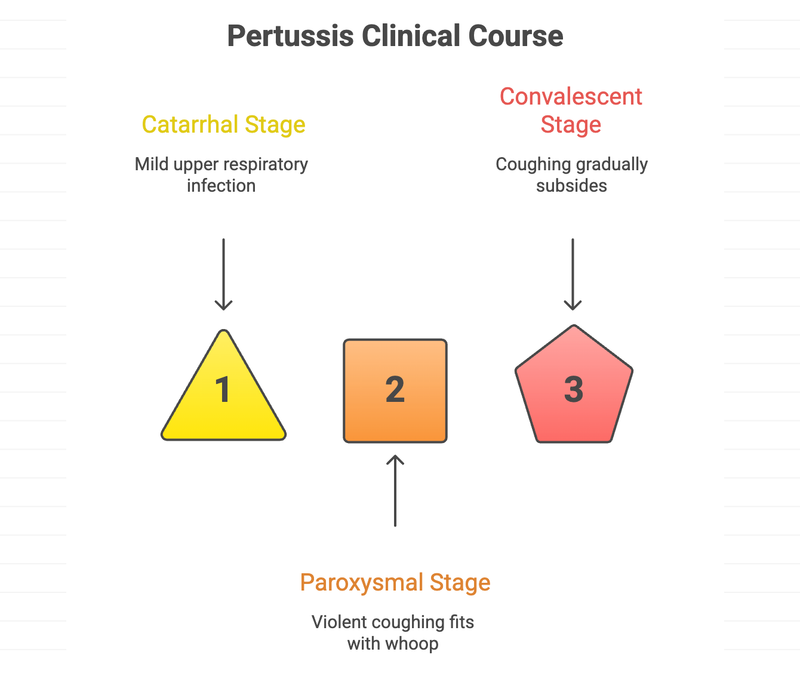

The clinical course of pertussis classically unfolds in three stages. The initial catarrhal stage lasts about one to two weeks and resembles a mild upper respiratory infection, with runny nose, sneezing, low-grade fever, and a gradually worsening cough. This stage is deceptively mild yet highly infectious.

The disease then enters the paroxysmal stage, which can persist for several weeks. During this phase, patients experience sudden, violent coughing fits followed by a forceful inspiratory gasp that produces the characteristic “whoop.” These episodes are often worse at night and may be accompanied by cyanosis, apnea, or post-tussive vomiting. Between coughing spells, patients may appear relatively well, which can be misleading given the severity of the attacks.

Recovery occurs during the convalescent stage, when coughing gradually subsides over weeks or even months. In older children and adults, illness may be milder and lack the classic whoop, presenting instead as a prolonged cough. Infants, however, are at highest risk: they may present with apnea rather than cough and are more likely to develop serious complications such as pneumonia or hypoxic brain injury.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing pertussis requires a combination of clinical suspicion and laboratory testing. Culture of B. pertussis from nasopharyngeal samples remains the gold standard due to its high specificity, but it is slow and insensitive, particularly later in the disease course. PCR testing has become the preferred diagnostic method because it is faster and more sensitive, especially during the first few weeks of illness. Serologic testing can be useful in later stages but is less reliable in vaccinated individuals.

A striking lymphocytosis on routine blood tests—particularly in infants—can provide an important diagnostic clue. Because early treatment is most effective, diagnostic testing should be performed promptly when pertussis is suspected, without delaying therapy.

Treatment

Supportive care is the mainstay of pertussis management, especially once the paroxysmal cough has developed. Infants may require hospitalization for oxygen therapy, hydration, and close monitoring due to the risk of apnea and exhaustion. Antibiotic treatment is most beneficial when started early, as it reduces transmission and may lessen disease severity if given before extensive toxin-mediated damage occurs.

Macrolide antibiotics such as azithromycin or clarithromycin are first-line therapies. Although antibiotics have limited impact on cough duration once the paroxysmal phase is established, they are still essential for preventing further spread. Patients should remain isolated until they have completed at least five days of effective antibiotic therapy.

Prevention

Vaccination remains the cornerstone of pertussis prevention. Routine childhood immunization with DTaP, followed by booster doses of Tdap in adolescence and adulthood, has dramatically reduced disease burden. Maternal vaccination during pregnancy is particularly important, as it provides passive protection to newborns during their most vulnerable period. High vaccination coverage, combined with post-exposure prophylaxis for close contacts and basic infection-control measures, remains essential to controlling pertussis at the population level.

Microbe Profile

Shape: Coccobacillus (rod, ovoid, or coccoid)

Gram Nature: Gram-negative

Spore Formation: Non-sporulating

Oxygen Requirement: Obligate aerobe

Optimal Temperature: 35℃ to 37℃

Optimal pH: 7.0 to 7.5

Essential Supplement: Nicotinamide

Taxonomic Classification

Domain: Bacteria

Kingdom: Pseudomonadati

Phylum: Pseudomonadota

Class:Betaproteobacteria

Order:Burkholderiales

Family:Alcaligenaceae

Genus:Bordetella

Species: Bordetella pertussis

-Neha Rao

Also Read: The MicroByte Pathogen Series: E. coli- Friend or Foe?

References

Melvin, J. A., Scheller, E. V., Miller, J. F., & Cotter, P. A. (2014). Bordetella pertussis pathogenesis: current and future challenges. Nature reviews. Microbiology, 12(4), 274–288. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3235

Duda-Madej, A., Łabaz, J., Topola, E., Bazan, H., & Viscardi, S. (2025). Pertussis—A Re-Emerging Threat Despite Immunization: An Analysis of Vaccine Effectiveness and Antibiotic Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(19), 9607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26199607

Wang, S., Zhang, S., & Liu, J. (2025). Resurgence of pertussis: Epidemiological trends, contributing factors, challenges, and recommendations for vaccination and surveillance. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 21(1), 2513729. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2025.2513729

Miguelena Chamorro, B., De Luca, K., Swaminathan, G., Longet, S., Mundt, E., & Paul, S. (2023). Bordetella bronchiseptica and Bordetella pertussis: Similarities and Differences in Infection, Immuno-Modulation, and Vaccine Considerations. Clinical microbiology reviews, 36(3), e0016422. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00164-22

Diavatopoulos, D. A., Cummings, C. A., Schouls, L. M., Brinig, M. M., Relman, D. A., & Mooi, F. R. (2005). Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough, evolved from a distinct, human-associated lineage of B. bronchiseptica. PLoS pathogens, 1(4), e45. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.0010045