Holobiome: Research I Articles I Updates I News I Series I Feed

Holobiome is a blog series that offers an AI-assisted summary of the latest research articles on human microbiome.

Rebalancing the Gut in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Probiotic Approach

Imagine your gut as a bustling world of microbes whose daily work can ripple out to distant organs. In people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), this microbial world often goes awry, producing gut-derived uremic toxins—compounds like indoxyl sulfate (IS) and p-cresol sulfate that normally flush out in urine but instead accumulate when kidneys fail. These toxins don’t just sit quietly; they can leak across a more permeable gut barrier (“leaky gut”), stir up inflammation, and worsen systemic health. This study explored whether giving targeted gut bacteria could help interrupt that harmful loop by reshaping the microbial landscape and dampening the production of these harmful molecules.

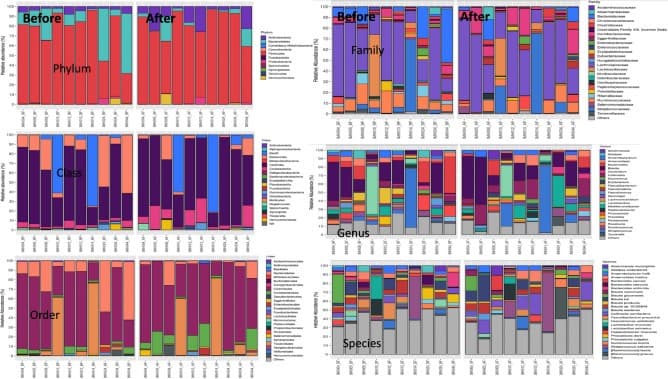

Researchers tested a probiotic strain called Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus L34—isolated from healthy infants and closely related to the well-known L. rhamnosus GG—in adults with stage 3–5 CKD. Over four weeks of daily supplementation, patients showed reduced levels of certain gut-derived toxins and signs of improved gut barrier function (measured by lower circulating fungal wall components and a trend toward lower endotoxin). Fecal microbiome profiling revealed that this probiotic intervention shifted the bacterial community: there was a decrease in Bacteroidota (a group that includes many Gram-negative anaerobes often linked with inflammation) and anincrease in Actinobacteria, which includes microbes that produce short-chain fatty acids and support gut homeostasis. L. rhamnosus itself became a distinguishing feature of the post-probiotic community.

What makes this story exciting from a microbiome perspective is that L. rhamnosus didn’t just ride along passively—it seemed to interact with the existing gut ecosystem to reduce dysbiosis and inflammatory signals. In cell culture experiments, molecules secreted by the probiotic lessened IS-induced inflammatory responses in intestinal cells, macrophages, and neutrophils, pointing to mechanisms where microbial metabolites and surface molecules influence host inflammation. While kidney function itself didn’t change over a month, these findings hint at how tweaking the gut microbiome might reduce systemic toxic stress and support health in CKD, illustrating the broader principle that microbes are not just passengers—they are active modulators of our internal chemistry.

The fecal microbiome analysis of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) at before and after 4 weeks of L. rhamnosus L34 (L34) administration as indicated by the abundance of bacteria in phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species is demonstrated (n = 10/group).

Microbial Imbalance in Early Life: Clues to UTI Risk

When we think about urinary tract infections (UTIs), especially in young children, we tend to picture bacteria ascending from the urethra into the bladder. But this study took a step back to look deeper at where many of those UTI-causing microbes originate: the gut microbiome, a complex ecosystem of trillions of bacteria that live in the intestine and interact with the immune system and body metabolism. By comparing children experiencing their first febrile UTI with healthy peers—before any antibiotics were given—the researchers found that the gut microbial landscape in affected children was clearly disrupted. Those with UTI had lower microbial diversity, often considered a marker of ecosystem health, with fewer of the beneficial butyrate-producing taxa like Bacteroides, Butyrivibrio, and Coprococcus that help fuel the gut lining and regulate inflammation, and relatively higher levels of bacteria including Escherichia that are known UTI culprits in the urinary tract.

This microbial imbalance, or dysbiosis, was reflected not only in the taxonomic profile but in metabolite signatures too. Stool metabolites tied to healthy microbial fermentation pathways—such as branched-chain amino acids—were reduced in the UTI group, while the control children showed stronger associations between beneficial microbes like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and compounds such as butyrate.

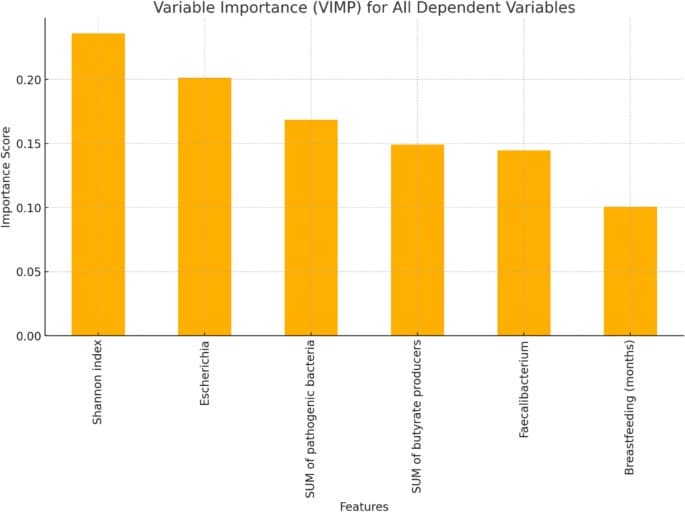

Importantly, machine learning models built from the microbiome data could distinguish between UTI cases and controls with impressive accuracy, with features like microbial diversity, Faecalibacterium abundance, and Escherichia levels emerging as key predictors. Breastfeeding duration also correlated with these microbial markers, hinting that early life shaping of the microbiome may influence UTI risk later in childhood.

Taken together, this pilot study suggests that gut microbiota don’t just passively reflect health status—they may play an active role in susceptibility to infection. Reduced diversity and a loss of short-chain fatty acid producers could weaken protective barriers or immune signaling, creating an environment where opportunistic Escherichia can flourish and seed infections beyond the gut.

The VIMP graph depicts the contribution of each dependent variable to the prediction of UTIs based on a Random Forest model. The variables are ranked according to their relative importance in improving the model’s predictive accuracy. Features e.g., Shannon index, the relative abundance of Escherichia, and SUM of pathogenic bacteria demonstrate the highest importance, suggesting their significant role in distinguishing between cases with and without urinary infections. This analysis highlights the key variables influencing the prediction and their potential biological relevance

Resilient Microbes: How the Gut Withstands PPIs and Probiotics

In this study, researchers looked at how a common acid-suppressing drug (a proton pump inhibitor or PPI) and a probiotic might influence the bustling ecosystem of microbes in the gut of adults infected with Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium that colonizes the stomach and can cause ulcers and chronic inflammation. PPIs are widely used in combination with antibiotics to help treat H. pylori, and past research has shown that altering stomach acidity can shift the gut microbiome, sometimes allowing bacteria normally found in the mouth or upper gut to flourish further down the intestinal tract and potentially reduce microbial diversity.

To explore how resilient the gut microbiome is in the face of such interventions, the team conducted a randomized clinical trial where participants received either pantoprazole (a PPI) plus a high dose of the probiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri or pantoprazole plus placebo over four weeks. Stool samples were collected before treatment, at the end of therapy, and one month later to track microbiome changes using shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

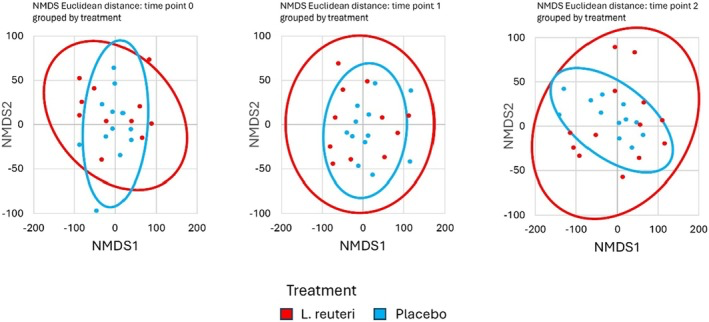

What they found was striking from a microbiome perspective: aside from the temporary appearance of L. reuteri in the probiotic group during supplementation,the overall structure and diversity of the gut bacterial community stayed remarkably stable, with no lasting shifts in alpha diversity (within-sample diversity) or beta diversity (differences in community composition) attributable to either the PPI or the probiotic. The L. reuteri strain surged in abundance only while it was being taken and faded back to baseline within a month after stopping, indicating transient colonization rather than permanent engraftment.

This resilience suggests that, at least over a short course of acid suppression and probiotic use, the adult gut microbiome resists long-term upheaval: core microbial communities remained dominant, and potential disruptions were minimal. While PPIs are known in other contexts to shift microbiota toward oral or other less typical taxa when used long-term, this study shows that brief exposure doesn’t leave a strong microbiome footprint, and that probiotic supplementation alone doesn’t dramatically reshape the gut ecosystem.

For science-curious readers, this trial underscores an emerging theme in gut microbiome research: the microbial ecosystem in healthy adults can be remarkably robust, capable of returning to its baseline configuration even after pharmacological and microbial perturbations. But it also highlights the transient nature of many probiotic strains—raising important questions about how and when such microbes can meaningfully alter gut communities in the long term.

NMDS ordination of gut microbiota composition. Each plot shows samples from L. reuteri + PPI (blue) and Placebo + PPI (red) at a given time point (T0, T1, T2). No distinct clustering by treatment is observed at any time point, indicating a high degree of overlap between groups.

Prevotella vs. Bacteroides: Why Your Gut Type Shapes Fiber Response

In this pilot dietary trial, scientists delved into how dietary fibers interact with the gut microbiome to shape both microbial communities and gut function in healthy adults. Instead of treating all participants as a uniform group, the researchers first looked at the baseline microbiome of each person and found two distinct patterns dominated by different key bacteria: one cluster was Prevotella-rich and the other Bacteroides-rich. These genera act like ecological leaders in the gut community and have very different metabolic capabilities—Prevotella is often associated with carbohydrate fermentation, while Bacteroides thrives on protein and varied diets—and this distinction turned out to be crucial for how each person’s microbiome responded to the fiber interventions.

Participants consumed either resistant starch from unripe banana flour (UBF), inulin, or a placebo over six weeks. When researchers looked at stool samples with 16S sequencing, they saw that only those in the Prevotella cluster experienced significant changes in their gut microbiota composition after consuming the resistant starch. This included shifts in the relative abundances of microbes like Phocaeicola (Bacteroides) vulgatus, Prevotella copri, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Blautia wexlerae, and Oscillibacter, hinting that these fibers were being metabolized by distinct microbial players.

Fascinatingly, the functional capacity of the microbiome also shifted in Prevotella-dominant individuals, with many predicted bacterial genes involved in metabolism and transport changing after resistant starch intake. Among these, pathways related to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis and transporters were enriched, suggesting that fiber intake might influence not just who's there, but what they’re capable of producing.

Although inulin had more modest effects, it did alter the proportions of short-chain fatty acids like propionate—key metabolites produced by fiber-fermenting bacteria that can influence gut health and host metabolism.

Altogether, this study highlights a growing insight in microbiome science: the effects of dietary fibers are deeply dependent on the existing microbial community. Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, knowing whether someone’s gut is dominated by Prevotella versus Bacteroides might help predict who will benefit most from a given fiber.

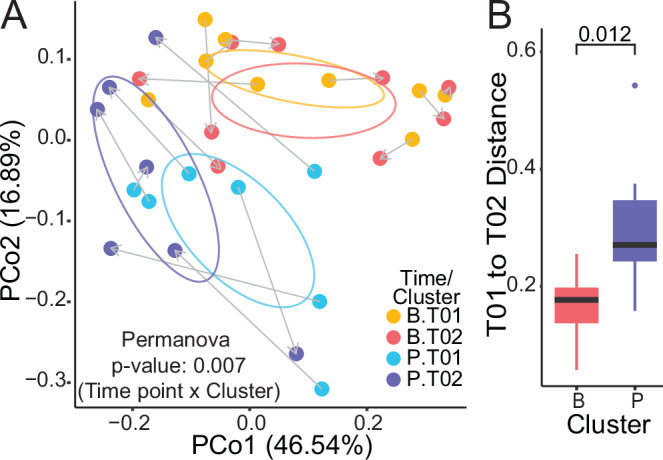

A Principal coordinate analysis of weighted Unifrac distances for subject samples before and after UBF treatment (Permanova analysis), and B intra-individual weighted Unifrac distances between T01 and T02 for each UBF cluster (Mann–Whitney analysis).

Probiotics and Parkinson’s: Targeting the Gut–Brain Axis

In this intriguing clinical trial, researchers explored whether nudging the gut microbiome with a multi-strain probiotic could benefit people living with Parkinson’s disease (PD), particularly those who also struggle with constipation. Growing evidence suggests that gut dysbiosis—an imbalance in the microbial communities of the digestive tract—is common in PD and may contribute to systemic inflammation and altered gut-brain signaling. Prior studies have shown that people with PD often have reduced abundances of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)–producing bacteria like Roseburia, Blautia, and Faecalibacterium, which are linked to gut health and anti-inflammatory effects.

Participants in the trial received either a daily oral dose of a probiotic cocktail (containing Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, and Enterococcus faecium) or placebo for 12 weeks. When scientists analyzed stool samples before and after, they observed that those taking the probiotic showed enrichment of bacterial groups associated with beneficial gut effects, such as the families Odoribacteraceae and Enterococcaceae, and notably increased levels of the species Blautia faecicola. Odoribacteraceae are known for their potential bile-acid-transforming capacity and may support gut resilience, while Enterococcus faecium, one of the probiotic strains, can thrive in the gut and potentially help crowd out harmful microbes.

Importantly, this shift in microbial profile occurred without broad changes in overall gut diversity, suggesting the probiotic selectively boosted certain taxa rather than causing wholesale disruption. On the host side, probiotic-treated participants experienced reductions in systemic inflammatory markers like TNF-α, hinting that microbial modulation may dampen inflammatory signaling. There were also improvements in some Parkinson’s motor and non-motor symptoms, possibly linking enhanced gut function—especially relief of constipation—to better medication absorption and overall wellbeing.

For the science-curious reader, this study illustrates how targeted probiotic interventions can reshape specific components of the gut microbiome in a clinical population and impact systemic biology beyond digestion. It echoes a broader theme in microbiome research: that select microbial taxa and their metabolites are powerful mediators of host physiology, especially in conditions where the gut-brain axis plays a key role.