Holobiome: Research I Articles I Updates I News I Series I Feed

Holobiome is a blog series that offers an AI-assisted summary of the latest research articles on human microbiome.

Microbiome Matters: How a Probiotic Strain May Support Better Sleep

In this intriguing study published in Scientific Reports, researchers dove into the age-old question of how our gut microbes might influence something as universal—and as delicate—as sleep. Rather than looking at sleep in isolation, the team examined how a specific probiotic strain, Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BLa80, could reshape the gut microbial community and whether those shifts might ripple outward to improve sleep quality in healthy adults. What makes this particularly compelling from a microbiome perspective is how the intervention didn’t just add a microbe, but nudged the whole gut ecosystem in measurable ways.

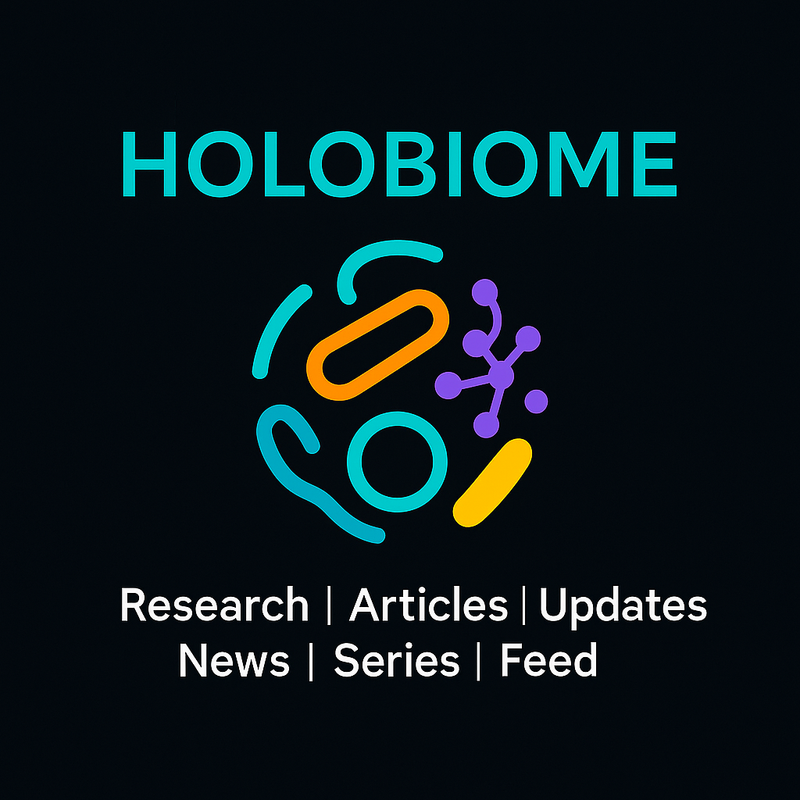

Over an eight-week period, individuals taking BLa80 showed distinct changes in their gut microbiota compared with those on a placebo. Although overall microbial diversity (i.e., alpha diversity) didn’t change much, the composition of the community did—a key insight for anyone interested in gut ecology. The team observed a decrease in the relative abundance of Proteobacteria, a phylum often linked to inflammation and dysbiosis, and an increase in groups like Bacteroidetes, Fusicatenbacter, and Parabacteroides, which are generally considered to be part of a beneficial gut profile. These shifts in microbial balance hint at how targeted probiotics can restructure ecological networks in the gut rather than merely establishing themselves as new tenants.

Beyond taxonomy, the researchers also probed potential functional consequences of these changes. Using predictive metagenomic analysis, they found that pathways involved in purine metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and arginine biosynthesis were enriched after BLa80 supplementation—suggesting that the altered microbiome might produce different metabolites with systemic effects. What's more, the probiotic itself demonstrated the capacity to produce GABA, a neurotransmitter that calms neural activity and is intimately involved in sleep regulation. This points to a fascinating mechanism where the gut microbiome could influence the gut-brain axis not just through broad community structure but via specific biochemical outputs.

Taken together, this research highlights how probiotic-driven modulation of the gut microbiota can ripple outward to affect host physiology. By nudging microbial populations and their metabolic pathways, BLa80 may help foster a microbial environment that supports better sleep, offering a glimpse into how future microbiome-focused therapies might target mind-body interactions.

Effect of BLa80 intervention on gut microbiota structure and function. (A) Analysis of differences in the genus levels. (B) Analysis of PICRUSt metabolic pathways. The STAMP analysis was used to identify significantly differentially enriched genera and metabolic pathways.

The Gut–Brain Axis in Stroke Recovery: A Microbial Perspective

In this fascinating study, scientists turned their attention to the trillions of microbes in our guts to understand how they might influence recovery after a major health event: acute ischemic stroke. While stroke recovery has traditionally been viewed through the lens of neurology and rehabilitation, emerging evidence underscores the gut–brain axis—a complex two-way conversation between our microbial communities and our nervous system—as a potential hidden player in how well people bounce back after such an injury.

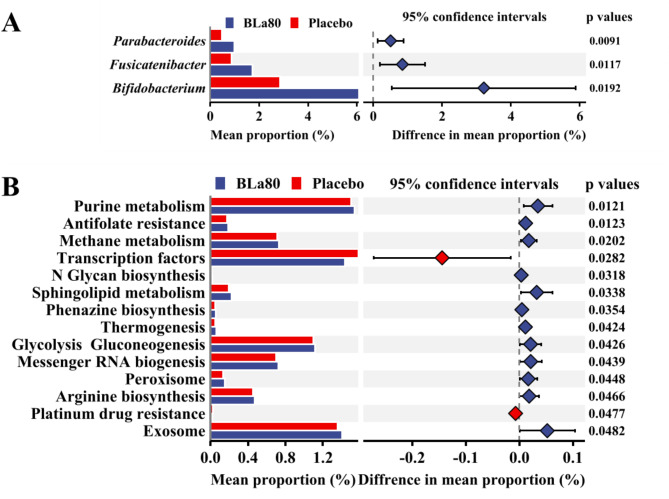

The researchers used shotgun metagenomic sequencing to deeply profile the gut microbiota of stroke patients, comparing those who had favorable functional outcomes three months after the event with those who did not. What stood out was that individuals with better recovery tended to have richer and more diverse microbial communities—a hallmark often associated with gut health—while those with poorer outcomes showed dysbiosis, marked by reduced diversity and an overrepresentation of opportunistic pathogens.

Delving into the specifics, the unfavorable group harbored higher levels of bacteria like Pseudomonas, Finegoldia, and Porphyromonas, taxa that have been linked to inflammation and disease in other contexts. In contrast, more favorable recoverers showed relatively higher abundance of typical beneficial or commensal microbes, suggesting that a balanced microbiome might support more robust resilience after neurological trauma.

The team also examined microbial metabolic signatures, finding differences in pathways such as ethylbenzene degradation and enzymes like 16S rRNA methyltransferase, which can influence host energy metabolism and inflammation. Interestingly, higher microbial production of pyruvate, a central metabolic molecule, was statistically tied to better outcomes, hinting at how microbial metabolism could modulate recovery processes, possibly through immune or neural signaling pathways.

Overall, this study paints a vivid picture of the gut microbiome as more than a passive bystander—it may be an active contributor to the complex biology of stroke recovery. While causality isn’t fully established yet, these microbial signatures open exciting avenues for future research into microbiota-based therapies aimed at bolstering resilience after stroke.

Gut microbiota differences in α‐ and β‐diversities between favorable (mRS 0–2) and unfavorable (mRS 3–6) outcomes in patients with ischemic stroke. (A) Boxplots representing class‐level α‐diversity measures (left to right): observed species, Chao1, and ACE indexes. Boxes represent the first to third quartiles, horizontal lines within the boxes show the median, and whiskers indicate variability outside the upper and lower quartiles. (B) PCoA at species‐level. The two components explain 30.0% and 11.9% of the variance. ACE: abundance‐based coverage estimator; mRS: Modified Rankin Scale; PCoA: principal coordinates analysis.

Diet, Diversity, and the Gut: Inside the Mediterranean Microbiome

In the study Influence of Dietary Components on the Gut Microbiota of Middle-Aged Adults, researchers explored how what we eat shapes the teeming ecosystem of microbes inside our gut—and how those changes might connect with overall health. Using fecal samples from middle-aged adults enrolled in a long-term Canadian cohort, they paired detailed dietary records with 16S rRNA sequencing to map out how adherence to a Mediterranean dietary pattern—a plant-rich way of eating high in fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and healthy fats—correlates with the structure and function of the gut microbiome.

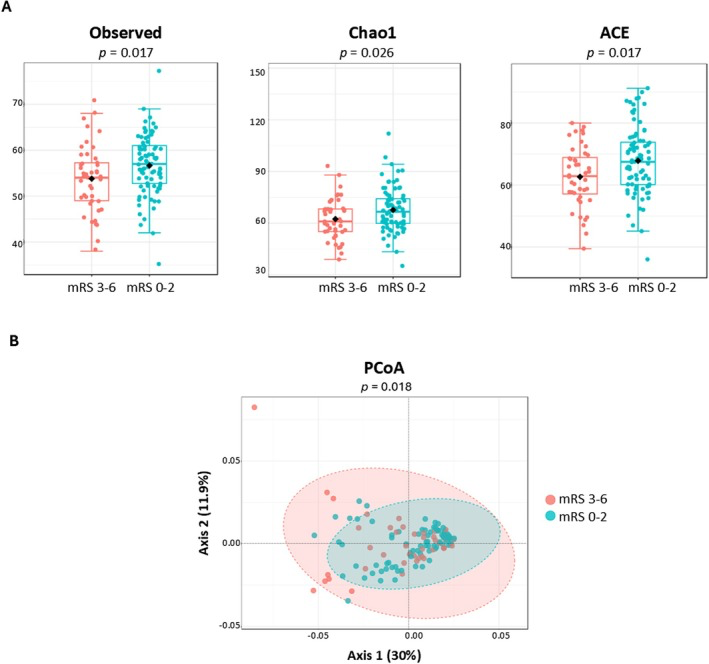

What they found was striking yet intuitive for microbiome enthusiasts: people whose diets most closely matched the Mediterranean pattern had a more diverse gut microbial community—a hallmark of a resilient, healthy gut ecosystem—compared with those eating less healthfully. Diversity matters because a broad array of microbial species creates a more robust network of biochemical reactions and helps resist colonization by harmful invaders.

Delving into specific taxa, higher Mediterranean diet scores were tied to greater abundances of fiber-degrading bacteria such as Prevotella, Parabacteroides, Clostridium cluster XIVb, Coprobacter, and Turicibacter. These microbes thrive on complex plant carbohydrates and, in the process, produce microbial metabolites that can cross the gut barrier and modulate host metabolism. At the same time, individuals with lower adherence to this dietary pattern had relatively fewer of these beneficial fiber-fermenters, underscoring how diet directly sculpts microbial community structure.

Beyond taxonomy, the study also linked dietary patterns to serum levels of microbial metabolites—biochemical fingerprints of microbial activity circulating in the bloodstream. Compounds such as p-hydroxy hippuric acid andindole-acetaldehyde, which arise from microbial transformation of dietary components, were higher in people eating more Mediterranean-style foods, hinting at mechanisms by which the gut microbiota translates diet into systemic signals that influence metabolic health.

Overall, this research paints a vivid picture of the gut microbiome as a mediator between diet and wellbeing. By nourishing fiber-degrading and metabolite-producing microbes with Mediterranean diet components, individuals may foster a gut ecology that supports metabolic resilience and guards against chronic disease.

Study participants. A Distribution of study participants into different diet quartiles based on their modified Mediterranean diet score (mMDS). Q1 = 1,2 mMDS; Q2 = 3,4 mMDS; Q3 = 5,6 mMDS; Q4 = 7,8 mMDS. The diet scores ranged from 0 (least healthy) to 9 (most healthy) and was based on weekly consumption of 9 food components adjusted by total energy intake– vegetables, legumes, fruits and nuts, dairy, whole grains, meat, fish, alcohol, and fatty acid ratio. No individuals scored 0 or 9. B BMI and WHR. Abbreviations: BMI; body mass index, mMDS; modified Mediterranean diet score, WHR; waist-to-hip ratio

Designing a Healthier Gut: Microbial Shifts During Weight Loss

This study explored how a comprehensive weight-loss program might reshape the gut microbiome in adults living with obesity, offering a fascinating glimpse into how microbial communities can intertwine with metabolic health. Over six months, participants followed either a multicomponent intervention (WLM3P) that combined caloric restriction, a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet, time-restricted eating, prebiotic and phytochemical supplementation, and behavioral support, or a standard low-carbohydrate diet. Researchers collected stool samples at the start and after six months to watch how the gut ecosystem responded to these different nutritional landscapes.

What emerged was a clear microbial signature of change in the more holistic program. Individuals in the WLM3P group showed increased alpha diversity, meaning their gut communities became richer and more varied over time—a trait associated with resilient, healthier microbiomes—while the standard diet group did not see such shifts. Most strikingly, certain beneficial bacteria like Faecalibacterium became more abundant in the WLM3P group. This genus is well known in microbiome research for its ability to produce short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate, compounds that nourish gut cells, modulate inflammation, and support metabolic function.

What makes these microbial changes especially compelling is their link with clinical outcomes. Higher levels of Faecalibacterium were associated with greater reductions in fat mass and visceral adiposity, suggesting that reshaping the gut ecosystem may help dial in more effective weight loss and body composition changes. While the exact mechanisms remain to be fully unraveled, this study supports the idea that the microbiome doesn’t just mirror what’s happening metabolically—it may help drive it. Adjusting diet and lifestyle in ways that promote beneficial microbes could thus be an important piece of the puzzle in managing obesity and its downstream health effects.

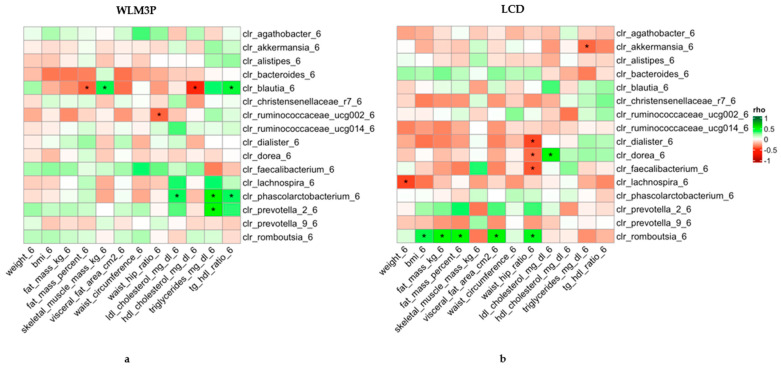

Heatmap of Spearman’s correlation coefficients between anthropometric and biochemical determinations and the abundance of microbial genera normalized by CLR after six months of intervention. The left panel (a) corresponds to the WLM3P group, and the right panel (b) to the LCD group. Each cell represents the correlation between a clinical parameter (x-axis) and a microbial genus (y-axis), with the color indicating the strength and direction of the correlation (green for positive, red for negative). Significant correlations are marked with an asterisk (*). The strength of the correlations (Spearman’s rho) is color-coded according to the scale on the right, ranging from −1 to 1.

The Metabolic Microbiome: How Fiber Drives Gut–Brain Communication

In this intriguing clinical trial, scientists harnessed a prebiotic fiber called inulin to explore how nudging the gut microbiota might influence the biochemical dialogue between the gut and brain in children with obesity. Rather than focusing only on body weight, the study examined how a six-month supplement of inulin could reshape microbial-linked metabolites that act as gut-brain axis (GBA) signaling compounds, such as biogenic amines and amino acids, which may play roles in appetite regulation and energy balance.

The gut microbiome isn’t just a collection of microbes—it is a metabolic engine that transforms dietary inputs into signaling molecules that travel through the bloodstream and communicate with the nervous system. Certain gut bacteria can convert dietary amino acids into neuroactive compounds like GABA, dopamine precursors, and other biogenic amines, and these molecules can influence central appetite control and metabolism. Genera such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Streptococcus are known producers of GABA and related compounds, while others like Faecalibacterium are associated with favorable metabolite profiles.

Compared with a placebo or generic dietary fiber advice, inulin supplementation led to significant increases in specific bioactive molecules involved in gut-brain communication—most notably putrescine, spermine, and tyrosine. These compounds stem from microbial metabolism and can influence neurotransmitter pathways; tyrosine, for example, is a precursor to dopamine, a key regulator of reward, motivation, and eating behaviors. The rise in these metabolites with inulin suggests enhanced microbial conversion of dietary substrates into molecules that could support more balanced appetite signaling.

Importantly, shifts in these GBA-related metabolites were associated with changes in the gut microbiota, reinforcing the idea that prebiotic fibers like inulin don’t act in isolation—they act through reshaping the microbial community and its metabolic output. This study offers an elegant example of how dietary interventions can influence host physiology not just by providing nutrients, but by steering the microbial ecosystem and its biochemical conversations with the brain.

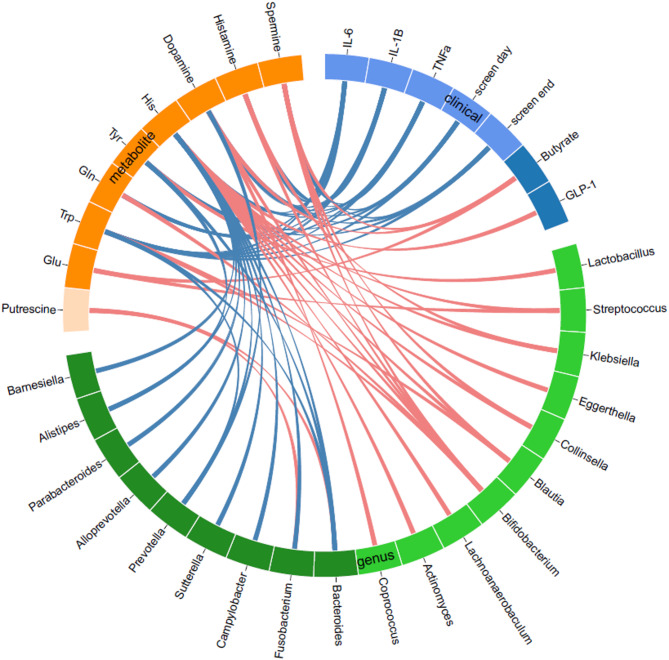

Relationships of GBA-related amino acids and biogenic amines with gut microbiota, physical activity, and biochemical parameters at baseline by circos plot. Red lines indicate positive associations, and blue lines indicate negative associations, analyzed by Spearman’s correlation coefficient with Benjamini-Hochberg correction with FDR = 0.05. GBA, gut-brain axis; Gln, glutamine; Glu, glutamate; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; His, histidine; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; Screen day, screen time on weekdays; Screen end, screen time on weekends; TNFa, tumor necrosis factor-α; Trp, tryptophan; Tyr, tyrosine.