Holobiome: Research I Articles I Updates I News I Series I Feed

Holobiome is a blog series that offers an AI-assisted summary of the latest research articles on human microbiome.

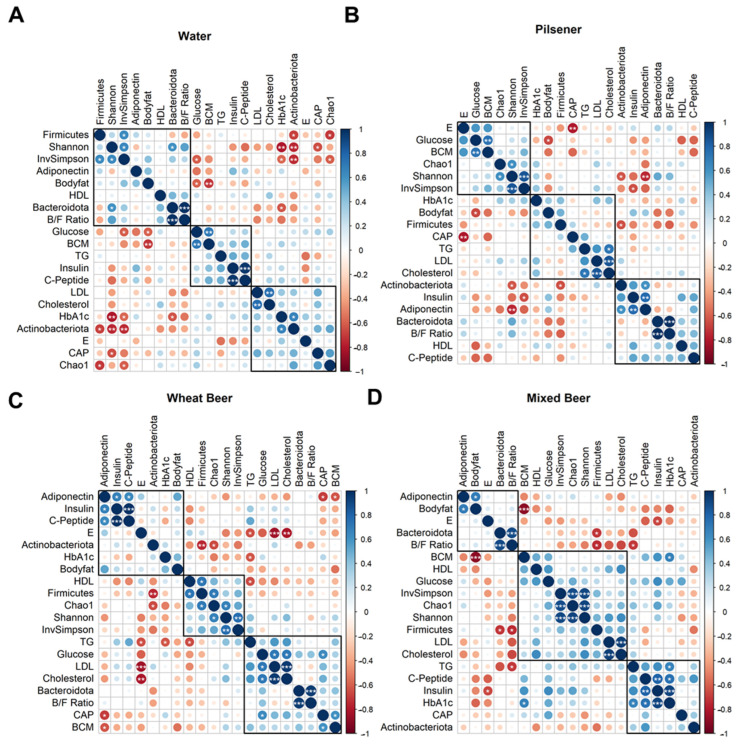

How Non-Alcoholic Beer Quietly Reshapes Your Gut Microbiome

When scientists set out to understand how what we drink shapes more than just our taste buds, they sometimes look at one of the body’s most intricate ecosystems: the gut microbiome. This study asked a simple yet intriguing question — does daily consumption of different types of non-alcoholic beer subtly shift the gut’s bacterial balance, alongside metabolic markers like blood sugar and fat? Over a month, healthy young men downed a pilsener, wheat beer, mixed beer, or plain water daily — and researchers not only tracked changes in their metabolism but also in their gut microbial communities using 16S rRNA sequencing of fecal samples.

Although the focus of the paper was primarily on metabolic outcomes, one clear signal emerged from the microbial data: drinking non-alcoholic pilsener beer had a detectable impact on the broad groups of bacteria in the gut. Specifically, there was a reduction in Firmicutes and an increase in Actinobacteria compared to the water-drinking control group. Firmicutes and Actinobacteria are two of the major bacterial phyla found in the human gut, and shifts in their relative abundance have been linked in other studies to changes in energy harvest, inflammation, and even body composition.

This work offers a provocative glimpse into how the calories and sugars we ingest not only ripple through our glucose and lipid metabolism but also brush against the microbial tapestry in our guts. The alterations observed hint that even subtle diet changes — like swapping water for a calorie-rich beverage — can nudge the gut microbiome’s structure, potentially influencing host health via microbial metabolism and signaling pathways. While the authors caution that the beer’s sugar content likely drives many of the metabolic effects, the microbiome shifts highlight the gut’s sensitivity to everyday dietary choices and underscore the need for deeper microbiome-focused studies in nutritional research.

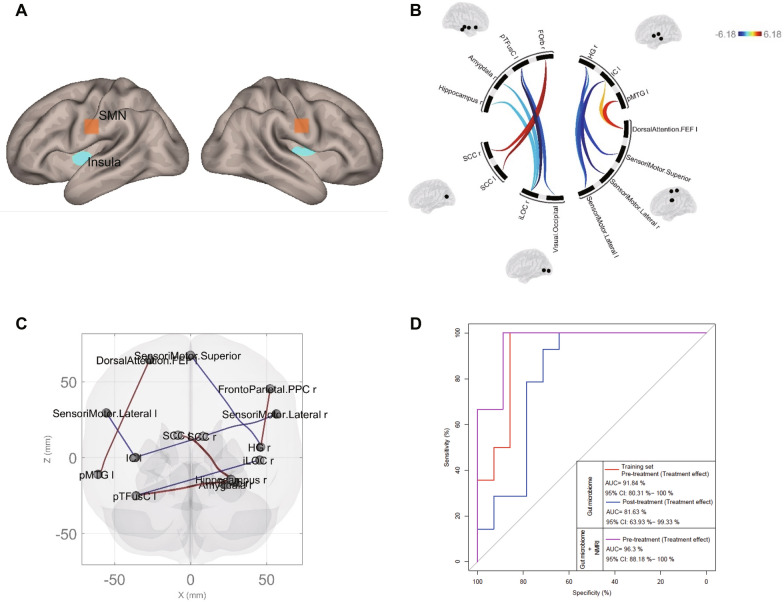

When Gut Bacteria Meet the Mind: Inside the Microbiome of Bipolar Depression

Imagine the trillions of bacteria in our gut not just helping digest food, but also whispering signals that shape our mood and brain function — that’s the emerging view of the gut-brain axis. In this study, researchers took a close look at the gut microbiomes of adolescents experiencing bipolar depression and compared them with healthy peers. What they found wasn’t just a subtle shift in bacterial counts, but a distinct microbial fingerprint that set depressed teens apart. While overall species richness (how many types of bacteria were present) wasn’t dramatically different, the community structure — the relative balance and composition of microbial species —was altered in those with bipolar depression.

Digging deeper revealed that many of these differences touched on microbes involved in key biochemical pathways. For instance, groups known to contribute to short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, aromatic amino acid metabolism, vitamin synthesis, and lipid handling showed distinct patterns in depressed adolescents compared to controls. SCFAs like butyrate are microbial metabolites with well-documented roles in maintaining gut barrier integrity and modulating inflammation — and they also have far-reaching effects on the nervous system.

Interestingly, after four weeks of treatment with the psychiatric drug quetiapine, the gut microbiome didn’t just remain static — specific bacterial species such as Odoribacter splanchnicus, Veillonella rogosae, and Hafnia alvei changed in abundance. Some of these microbes are linked to SCFA production and metabolism of nutrients that intersect with brain signaling pathways. The study even showed that patterns of gut microbes could distinguish depressed adolescents from healthy ones with high accuracy and predict how well a patient might respond to treatment when combined with brain imaging data.

This work underscores how deeply the gut’s microbial community is interwoven with brain health, especially during adolescence when both the microbiome and the nervous system are still developing. Microbial shifts in metabolic functions relating to SCFAs, amino acids, lipids, and vitamins offer tantalizing clues that the tiny tenants of our gut may play outsized roles in mood regulation — opening doors to novel microbiome-informed diagnostics and therapies for mood disorders.

The Gut–Lung Connection: Microbes, Nutrition, and Chronic Lung Disease

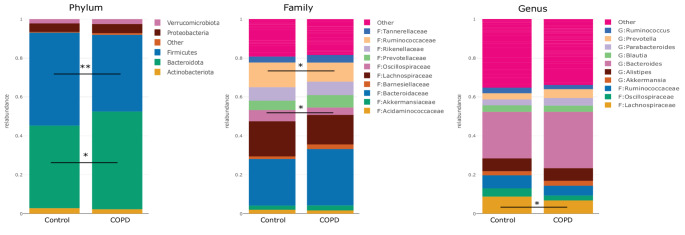

When we think about chronic conditions like Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), the lungs usually take center stage — but emerging science is pointing to a surprising partner in this story: the gut microbiome. In this clinical study, researchers explored how the communities of microbes living in the intestines differ between people with COPD and healthy adults, and whether targeted multi-nutrient supplementation — including elements like prebiotics and fiber — might nudge those bacterial populations toward a healthier balance.

At the heart of the research is the idea of microbial dysbiosis — that is, an imbalance in the ecosystem of bacteria, archaea, and other microbes that normally help digest food, train the immune system, and produce beneficial metabolites. In COPD, this balance appears to be disrupted, with some beneficial microbes reduced and others — including taxa linked to inflammation — relatively enriched. Although specific species weren’t highlighted in every arm of this trial, the overall pattern of dysbiosis reflects what other studies have shown: reduced diversity and altered ratios among major bacterial groups, such as Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria, echoing findings in related gut–lung microbiome research.

Importantly, the study also tested whether multi-nutrient supplements — components thought to fuel beneficial bacteria or support intestinal barrier integrity — could shift the gut microbiome. After three months of supplementation, participants with COPD showed changes in the composition of their gut bacterial populations, hinting that diet-based interventions may partially counteract dysbiosis. These microbial shifts were accompanied by improvements in markers of inflammation and physical health, suggesting that gut microbes may be active players in shaping systemic inflammation — a key driver of COPD progression.

This work underscores a broader insight gaining traction among microbiome researchers: our gut bacteria don’t just stay confined to digestion. Through the gut–lung axis, microbial metabolites and immune signals can ripple far beyond the intestine, potentially influencing inflammatory processes in the lungs and other organs. Understanding and modulating microbial communities thus offers a promising, if still early, front in tackling chronic diseases like COPD.

Can Probiotics Influence Parkinson’s Through the Gut?

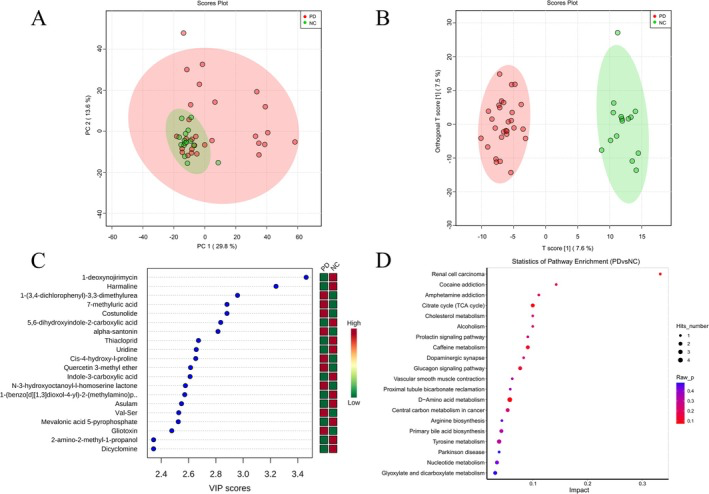

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is best known for its tremors and movement challenges, but its roots may stretch far beyond the brain — reaching deep into the gut’s microbial ecosystem. In this clinical study, researchers explored how a 12-week course of probiotic supplementation influenced both neurological symptoms and the gut microbiome of people living with PD. Prior work has suggested that disturbances in the gut microbial community may be linked to the enteric nervous system and the pathology of PD through the so-called gut–brain axis, and here we see that connection playing out in real human subjects.

Before treatment, PD patients exhibited characteristic dysbiosis — imbalanced microbial communities compared with healthy controls — marked by differences in dominant bacterial groups, including higher relative abundance of certain Firmicutes and Actinobacteria taxa. After adding a multi-strain probiotic blend containing beneficial bacteria such as Bacillus licheniformis, Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Enterococcus faecalis, notable shifts emerged in the gut ecosystem. Although the overall diversity (a measure of how many distinct bacterial types are present) didn’t change dramatically, specific microbial populations shifted significantly. There was an increase in Actinobacteria and Negativicutes — groups often linked with metabolic and immune functions — alongside rises in beneficial genera like Gordonibacter and Lactobacillus casei. At the same time, potentially pro-inflammatory taxa such as Enterococcus faecium and Comamonas kerstersii diminished after probiotics.

These microbial alterations weren’t just biological curiosities — they tracked alongside clinical improvements in PD motor symptoms and REM sleep behavior disorder severity. The study also tied changes in specific gut bacteria to shifts in serum metabolites, suggesting that microbial products might travel from the intestine into circulation, influencing nervous system pathways. This aligns with growing evidence that the gut microbiome can produce metabolites that modulate inflammation, neurotransmitter pathways, and systemic health.

Together, these findings hint at a compelling narrative: modulating the gut microbiome with targeted probiotics may help reshape microbial communities in ways that support neurological health, adding another layer to how we understand the gut–brain conversation in Parkinson’s disease.