Holobiome: Research I Articles I Updates I News I Series I Feed

Holobiome is a blog series that offers an AI-assisted summary of the latest research articles on human microbiome.

The Surprisingly Steady Gut: Why Exercise and Calorie Cuts Didn’t Reshape the Microbiome

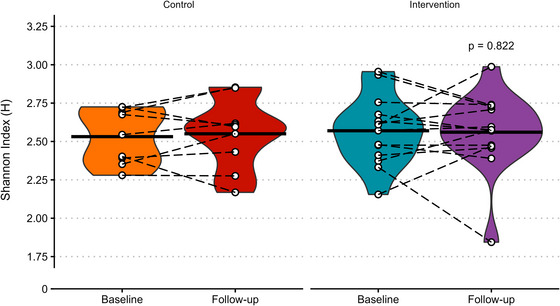

Imagine a world where you overhaul your lifestyle, slashing calories and hitting the treadmill hard and yet the invisible ecosystem inside your gut barely bats an eye. That’s exactly what a recent randomised controlled trial found when scientists tested whether combined energy restriction and vigorous exercise could reshape the human gut microbiome. They enrolled sedentary adults with overweight or obesity into a three-week regimen that cut daily energy intake and added structured exercise, and then profiled their gut microbial communities using high-resolution shotgun metagenomic sequencing. Despite participants losing weight and improving markers like insulin sensitivity, leptin, and cholesterol, the overall composition and diversity of their gut microbiota stayed essentially the same from start to finish.

From the microbiome perspective, this is a fascinating twist. Researchers had hypothesized that the gut ecosystem home to hundreds of species whose collective genomes vastly outnumber our own might shift in response to such a dramatic change in host energy balance and physiology. In other contexts, diet and exercise have been linked with changes in species like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii or Akkermansia spp., microbes known for their roles in fermenting fiber into short-chain fatty acids or modulating host metabolism. But in this tightly controlled human study, no significant shifts in alpha diversity (within-person richness) or beta diversity (between-person differences) were detected after the intervention.

This suggests that the early metabolic improvements seen with weight loss might be driven more by host tissues changes in adipose, muscle, and systemic metabolism than by rapid reorganization of gut microbial communities. It also underscores how resilient the adult gut microbiome can be: even under pronounced energy stress and increased physical activity, the core microbial landscape held steady. For science-curious observers, it’s a reminder that not all beneficial lifestyle shifts translate into immediate microbiome changes, and that host and microbe likely dance to their own rhythms in the complex choreography of health.

Black crossbars represent the mean, white points show individual data with paired observations joined by dashed black lines and P‐value shows ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) effect of group. N = 9 in control and 14 in intervention.

Prevotella, Bifidobacterium, and the Battle for Fiber in the Gut]

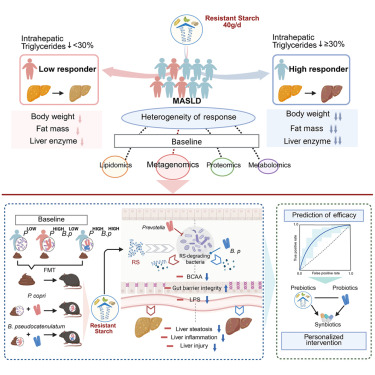

When we think about the foods that feed us, it’s easy to overlook the fact that many of those calories never reach our own cells they’re intercepted by the bustling community of microbes living in our colon. A new study in Cell Metabolism looked at how resistant starch, a type of fermentable dietary fiber that escapes digestion in the small intestine, interacts with the gut microbiome to influence health in people with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatosis liver disease (MASLD). Rather than responding uniformly, individuals’ metabolic improvements after resistant starch supplementation varied widely, and the key to that variation lay in which microbes were present in their guts to begin with.

From a microbiome perspective, this makes perfect sense: resistant starch isn’t absorbed by the host but instead becomes a feast for certain bacteria. The trial showed that the presence and activity of specific microbial taxa determined how effectively resistant starch could be fermented and turned into beneficial metabolites. For example, Prevotella species often associated with carbohydrate fermentation were found to impair resistant starch utilization when dominant, blunting metabolic benefits. In contrast, the presence of Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum a carbohydrate-degrading, SCFA-producing species helped restore the ability to break down resistant starch even when Prevotella was abundant. These microbes feed on resistant starch and produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate and acetate, which are known to support gut barrier integrity, regulate immune activity, and improve systemic metabolic signaling.

This study highlights that the gut microbiome isn’t just a passive reflection of our diet it actively mediates how dietary components like resistant starch translate into health outcomes. Individuals with a microbiome rich in resistant-starch-utilizing bacteria experienced stronger improvements in liver and metabolic markers, while others with different microbial profiles saw blunted effects. That means the future of dietary therapies for metabolic diseases may lie in precision nutrition tailoring fiber and prebiotic interventions to a person’s unique gut microbial ecosystem. Far from one-size-fits-all, the health effects of a given food may depend as much on who lives in your gut as what you eat.

Graphical Representation

How Gut Bacteria Shape Personalized Responses to Dietary Fiber

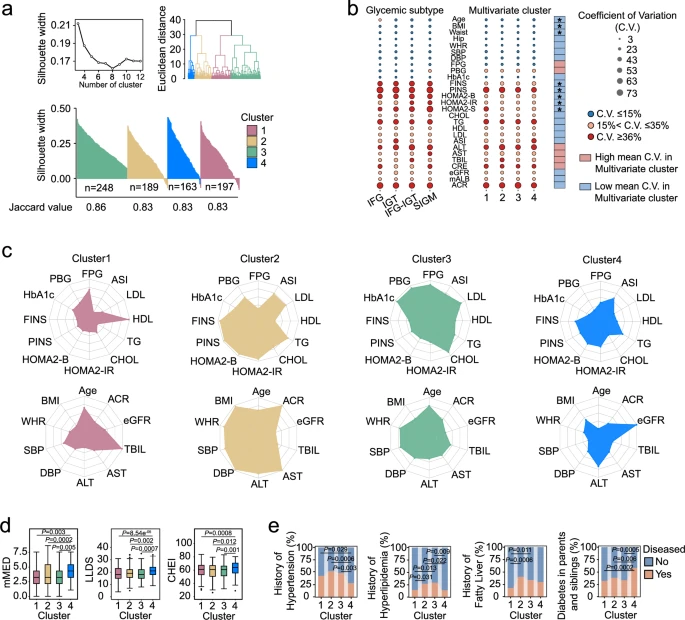

Our gut microbiome is more than a bystander when it comes to how we respond to what we eat; it's often the deciding factor. In a large, six-month randomized trial involving over 800 people with prediabetes, scientists tested how dietary fiber supplements influenced blood sugar control, insulin resistance, and metabolic health. At first glance, the fiber intervention didn’t improve outcomes across the whole group. But when researchers dug deeper using a combination of clinical clustering, microbiome profiling, and predictive modeling, a remarkable pattern emerged: individual differences in gut microbial communities helped explain who benefited and who didn’t.

At the heart of the story is how gut bacteria interact with dietary fiber. Humans lack the enzymes to digest most fiber, so it’s up to microbes to break it down. Certain bacteria including members of the genera Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides are adept at fermenting complex carbohydrates into bioactive short-chain fatty acids like acetate and butyrate. These metabolites can influence host physiology by enhancing insulin secretion, modulating inflammation, and improving gut barrier function. In this trial, subjects whose baseline microbiomes were enriched with fiber-utilizing taxa showed more pronounced changes in microbial community structure after intervention and had better glycemic improvement compared to others.

Researchers identified distinct microbial signatures and serum metabolite patterns that distinguished different metabolic clusters of participants. These signatures were not just academic: a machine-learning model trained on baseline microbiome features could predict who was likely to experience meaningful blood-sugar improvements from fiber supplementation. This highlights that the same dietary strategy doesn’t work for everyone; the makeup of your gut microbes matters a great deal.

For science-curious readers, the take-home is clear: dietary fiber’s health benefits are not solely a property of the food itself, but a product of the dialogue between that food and the microscopic residents of your gut. Personalized nutrition that accounts for these microbial differences could be a powerful tool in preventing or managing metabolic diseases like type 2 diabetes.

a) K-means multivariate clusters of the subjects with prediabetes. b) Coefficients of variation (C.V.) of clinical parameters between glycemic subtypes and multivariate clusters. Differences were tested with Mann–Whitney U test (two-sided). * P < 0.05. c) Clinical parameters in multivariate clusters. The radar charts show the medians of each cluster with the corresponding standardized level (z-scores) of the parameters. d) Quality of dietary patterns in multivariate clusters. Boxes show the medians and the interquartile ranges, the whiskers denote the lowest and highest values that were within 1.5 times the interquartile ranges from the first and third quartiles, and outliers are shown as individual points. Comparisons among clusters were used with Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s test (two-sided) for multiple comparisons. e) Metabolic diseases history in multivariate clusters. Comparisons among clusters using the chi-square test (two-sided). All experiments were performed with biological replicates. The sample sizes are as follows: n = 197 in Cluster1, n = 189 in Cluster2, n = 248 in Cluster3, n = 163 in Cluster4.

Inside the Microbiome–Gut–Brain Axis of Early Childhood

Our gut microbiome isn’t just about digestion it might also help shape how our brains develop and regulate emotion. A groundbreaking study published in Nature Communications followed children from early toddlerhood into middle childhood and found that the composition of the gut bacterial community at age two was linked to emotional patterns like anxiety and depression several years later. This research connects early microbial signals to brain network connectivity and, ultimately, internalizing symptoms such as worry and withdrawal around school age, highlighting a striking example of the microbiome-gut-brain axis in development.

What’s particularly fascinating from a microbiome perspective is which bacteria were implicated. The researchers identified microbial profiles patterns of abundance across bacterial groups that predicted differences in the functional architecture of emotion-related brain networks. Bacteria within the order Clostridiales and especially the family Lachnospiraceae stood out: variation in these taxa at age two was associated with changes in resting-state brain connectivity measured at age six and with internalizing symptoms reported at 7.5 years. These microbes are known members of the gut ecosystem with metabolic capabilities that influence host physiology, including fermentation of dietary fibers and production of metabolites that can interact with immune and neural pathways.

The study also found that overall microbial diversity is a common indicator of gut ecosystem richness related to specific brain network patterns, suggesting that not only individual bacterial groups but also the structure of the gut community may contribute to how neural circuits involved in emotion form during development.

While this research doesn’t prove that gut bacteria cause later emotional outcomes, it does provide compelling evidence that early childhood microbiome composition is intertwined with brain connectivity and emotional health years down the line. In other words, the bacterial communities that take root in our guts during a critical developmental window may be among the subtle architects of how we feel and think later in childhood.

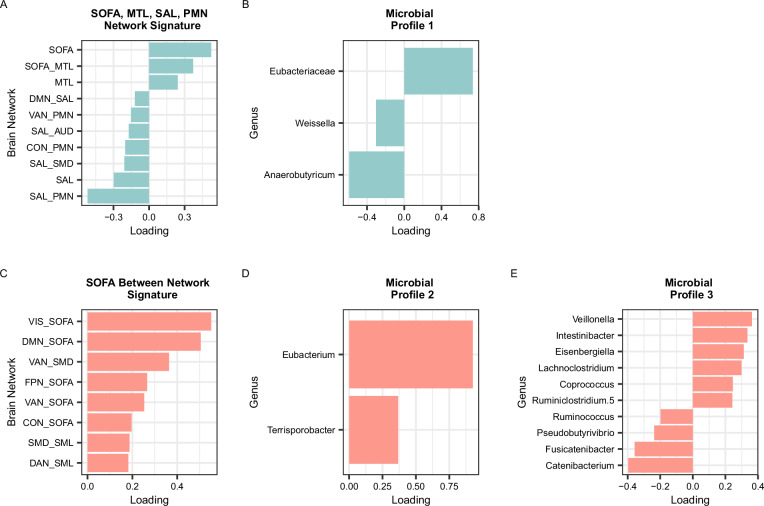

A SOFA, MTL, SAL, PMN Network Signature. B Microbial Profile 1. C SOFA Between Network Signature. D Microbial Profile 2. E Microbial Profile 3. Colors (blue or salmon) and rows correspond to the brain signature that the microbial profile was derived from (blue = SOFA, MTL, SAL, PMN Network Connectivity Brain Signature; salmon = SOFA Between Network Connectivity Brain Signature). Only variables with VIP > 1 are shown. SOFA = striatal-orbitofrontal-amygdalar, MTL = medial temporal lobe, DMN = default mode network, SAL = salience, PMN = parietomedial network, VAN = ventral attention network, AUD = auditory, CON = cingulo-opercular, SMD = somatomotor dorsal. For microbes that were unable to be classified to the genus level, the family name is shown. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Why the Gut Microbiome Matters in Lung Infections

Emerging research is reframing how we understand infections like pneumonia not as purely local lung events, but as systemic interactions shaped by microbial life deep in the gut. A recent study found that metabolites produced by gut bacteria from the essential amino acid tryptophan can influence how severely pneumonia unfolds, spotlighting the powerful gut–lung axis in human health. Rather than focusing only on pathogens in the lungs, this work shows that microbial chemistry in the gastrointestinal tract sends signals that ripple through the immune system and affect respiratory responses.

The key molecule at play is indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), a compound generated when gut microbes metabolize tryptophan, a dietary amino acid. Many gut bacterial taxa such as Bacteroides and Clostridium species process tryptophan into a suite of indole derivatives, including IAA, indole-3-propionic acid, and other metabolites that can signal to host tissues far beyond the gut. These metabolites can cross the intestinal barrier, enter the bloodstream, and interact with host receptors like the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), which modulates immune cell behavior and inflammatory pathways.

In large human cohorts and experimental models, higher circulating levels of IAA were linked with worse outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia, suggesting that the way an individual’s gut microbiome metabolizes tryptophan can shape systemic immune readiness and inflammatory responses during lung infections. Intriguingly, in mouse experiments, administering IAA altered pulmonary immune responses via AhR and influenced how neutrophils fought infection, indicating that microbial metabolites can both help and harm depending on context.

This study highlights that gut bacteria are not passive bystanders in distant diseases like pneumonia. Their metabolic outputs, especially products of tryptophan metabolism serve as biochemical messengers that tune host immunity across organs. For science-curious readers, it’s a powerful reminder that our microbiome’s chemistry can ripple well beyond digestion, influencing immune landscapes in the lung and potentially shaping the course of infectious disease.

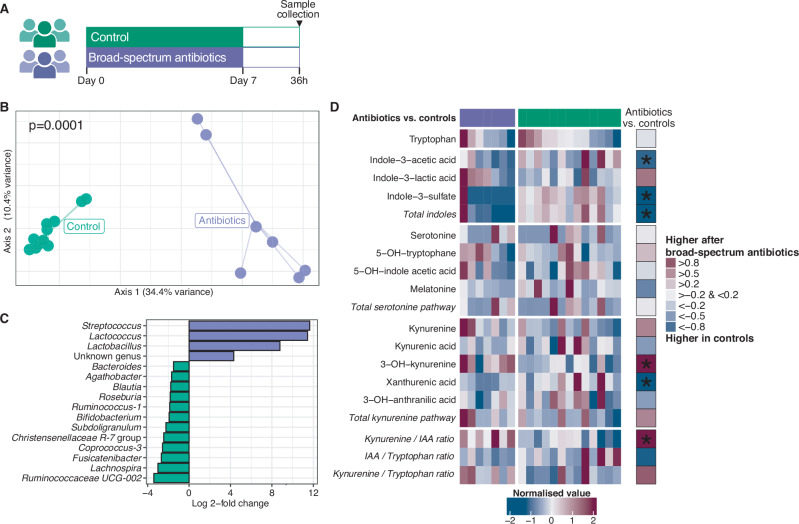

A) Twenty participants were randomized to receive either no treatment (control; n = 13) or oral broad-spectrum antibiotics for 7 days in order to disrupt the gut microbiota (n = 7). Following a 36 h washout period, blood plasma was collected in which tryptophan metabolites were measured using targeted metabolomics. B) Broad-spectrum antibiotics resulted in altered gut microbiota community composition. Significance of differences in community composition between groups is determined using permutational multivariate ANOVA (two-sided) with Bray-Curtis dissimilarities at the level of amplicon sequence variants. C) This compositional difference between groups was driven by higher relative abundances of Streptococcus, Lactococcus, and Lactobacillus spp. in participants who received broad-spectrum antibiotics, and lower relative abundances of several obligate anaerobic bacteria (e.g. Ruminococcaceae UCG-002 and Bifidobacterium spp.), as identified by a DESeq2 model. D) Heatmap depicting plasma tryptophan metabolite levels in the participants with broad-spectrum antibiotic-mediated gut microbiota modulation and controls. The rightmost columns show effect sizes (Hedges’ g) of comparisons between the antibiotics group and controls. ‘*’ marks p < 0.05, as tested by two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.