Holobiome: Research I Articles I Updates I News I Series I Feed

Holobiome is a blog series that offers an AI-assisted summary of the latest research articles on human microbiome.

The Gut Makeover That Lasted Four Years

Imagine you could transplant a “lean, healthy guts” microbial community into someone struggling with obesity could it have lasting benefits? That’s basically what happened in this long-term follow-up. Researchers gave a group of adolescents with obesity a stool transplant (from lean donors), then checked back with them four years later to see what stuck and whether their gut microbes and metabolism changed. Surprisingly, even years later, many of the donor-derived bacteria and viruses were still present.

The study found lasting shifts in the recipients’ gut microbiome: their overall “richness” meaning the number of different microbial species was higher than in those given a placebo, even after four years. Also, there was a sustained change in which microbes and functions dominated their guts, suggesting that the transplant didn’t just produce a short-term ripple, it helped reshape the microbial community in a stable way.

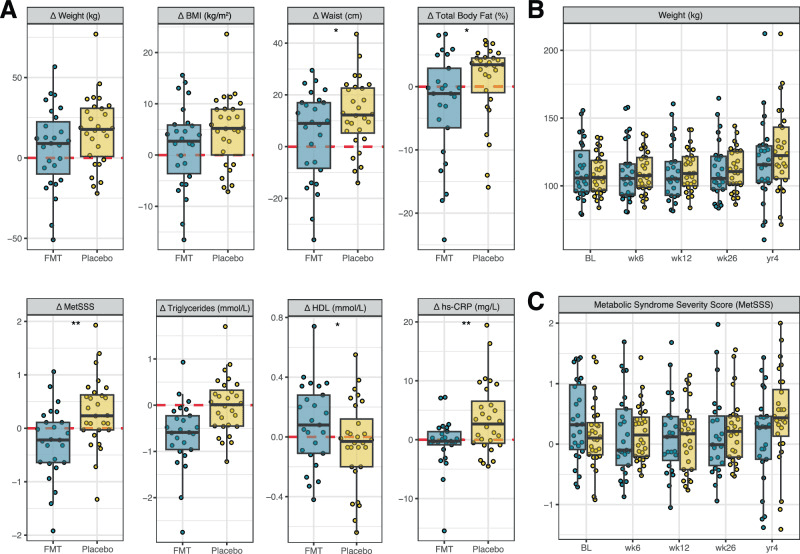

On the health front, people who got the transplant ended up with smaller waistlines and lower body-fat percentages, along with less inflammation and a better “good cholesterol” level. That doesn’t prove the new microbes directly caused those benefits. Many things (diet, lifestyle, growth) may play a role but the long-term survival of the transplant microbes suggests the gut ecosystem itself might help steer metabolism, fat distribution, and inflammation over years.

In short: this study shows the gut microbiome isn’t fixed. With a one-time “rewiring,” we might be able to reset it and help improve body composition and metabolic health long-term. It points to a future where managing obesity might involve not just diet and exercise, but also nurturing the right microbial community inside us.

A) Individual changes (Δ) in anthropometric and metabolic outcomes at 4 years compared to baseline. Points represent individual participants. The boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR) split by the median, with whiskers expanding up to 1.5× the IQR. The dashed red line at 0 represents the reference baseline value. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 for between-group differences, derived from linear models; p-values are nominal (unadjusted for multiple comparisons) and two-sided. Exact sample sizes for each analysis are indicated Fig. 1. BMI body mass index, FMT faecal microbiota transplantation, HDL high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, hs-CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; and metabolic syndrome severity scores (MetSSS). B Weight and C MetSSS over the full study period, including only participants (FMT, blue; Placebo, yellow) who returned for the 4-year follow-up.

The Gut-Friendly Power of Legumes for Pre-Diabetes

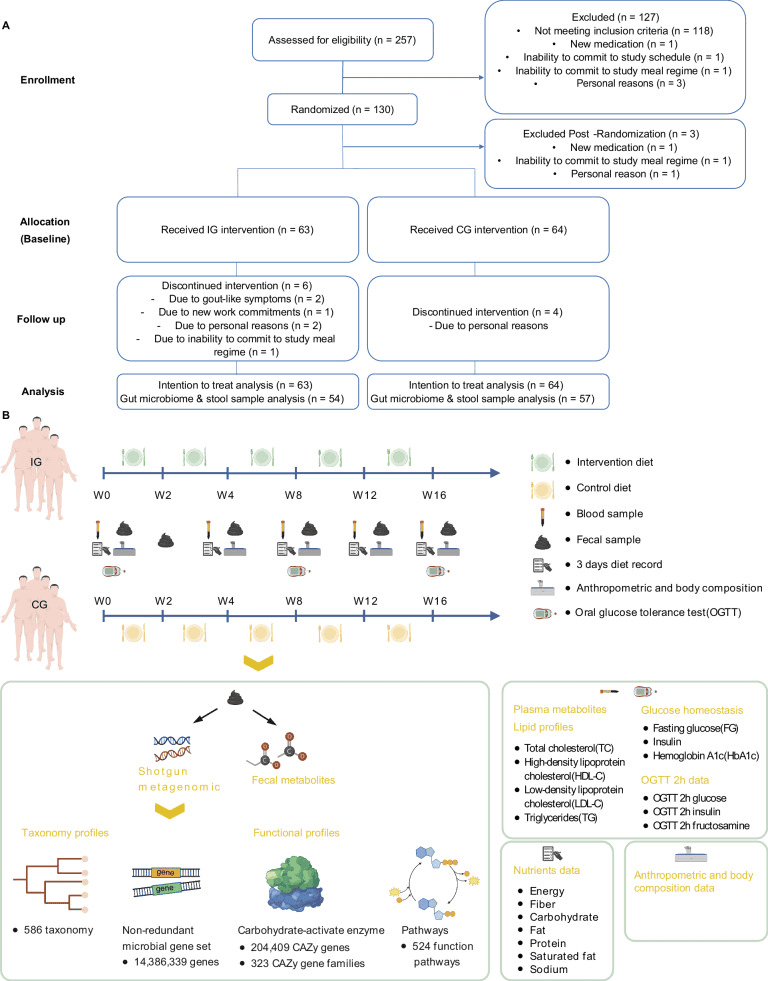

Imagine improving blood sugar and cholesterol not just by eating fewer calories, but by choosing foods that feed the tiny helpers living in your gut. That’s exactly what this randomized controlled study explored when prediabetic adults were placed on a legume-enriched diet think lentils, chickpeas, beans along with calorie restriction. While both groups lost weight, the group eating more legumes saw greater improvements in blood sugar control and cholesterol, and the researchers traced a key part of this success back to changes in the gut microbiome.

Legumes are naturally rich in fiber, and gut bacteria thrive on this slow-digesting fuel. The participants who added more legumes to their diet developed higher levels of fiber-degrading microbes, the types of bacteria that specialize in breaking down plant fibers humans can’t digest on their own. In return, these microbes produced compounds linked to better metabolic health, particularly shifts in bile acids and amino-acid–related metabolites, which play behind-the-scenes roles in regulating cholesterol, inflammation, and glucose balance.

What makes this microbiome twist especially interesting is that these changes weren’t just a side effect of weight loss. Both groups lost weight yet only the legume-focused group experienced meaningful improvements in LDL cholesterol and HbA1c, the long-term marker of blood sugar levels. This suggests the benefit came not just from eating less, but from feeding the right microbes with the right foods.

The takeaway is surprisingly empowering: choosing foods that nourish your gut like beans, lentils, and other legumes may help shift your internal microbial community toward one that supports better metabolic health, especially for those at risk of diabetes. In short, your dinner isn’t just feeding you, it’s feeding your microbes, and they might just return the favor in ways that protect your health from within.

A Consort Flow Diagram of the study outlining the participant recruitment, assessment for eligibility, randomization, intervention allocation, and follow-up phases, concluding with the analysis stage. B Study design: The dietary intervention was administered to both groups over a period of up to 16 weeks. Blood samples were collected at baseline, week 4, week 8, week 12, and week 16. Additionally, dietary records were maintained, and both anthropometric measurements and body composition tests were conducted. We also conducted OGTT at baseline, week 8 and week 16. Fecal samples were collected at baseline, week 2, week 4, week 8, week 12, and week 16. We profiled the fecal metagenome on all fecal samples and conducted targeted metabolomics of fecal and serum samples collected at baseline, week 4 and week 16. Lipid profile and glucose homeostasis biomarkers were assessed in all blood samples collected across five time points. For the metagenomic data, we undertook taxonomy annotation and functional characterization. The functional annotation encompassed the construction of non-redundant gene sets, annotation of carbohydrate-active enzymes, and annotation of functional pathways. Created in BioRender. Latypov, O. (2024) https://BioRender.com/w88p289.

Feeding the First Microbes: How Milk-Coated Fats Shape a Baby’s Gut

Babies don’t just grow thanks to milk their first microbes often get a big hand from what they drink. In this study, researchers looked at infants fed a special formula whose fat droplets were coated with milk phospholipids instead of the usual formula fats. They tracked these babies’ gut microbes (via stool samples) at birth, at three months, and again at one year.

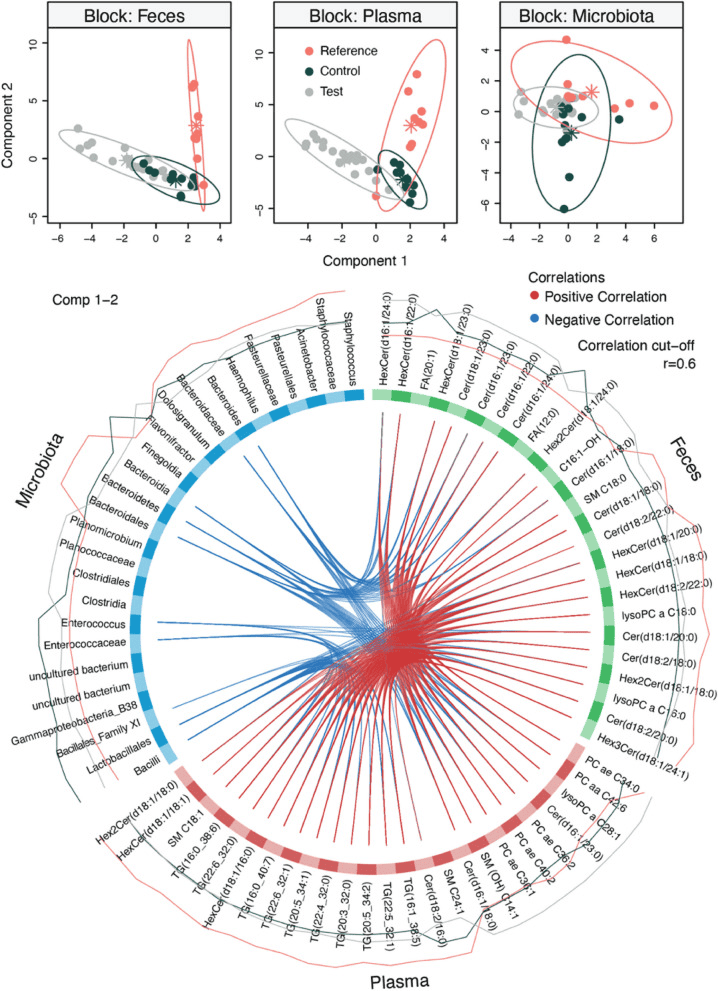

The results showed that the type of fat in early feeding mattered for which bacteria established themselves in the gut. Some groups including bacteria from the genus Bacteroides and related families were more abundant in infants who received the “milk-like” droplet formula compared with traditional formula. Meanwhile, microbes such as those from the family Enterococcaceae more common in less optimal gut-ecosystem setups were less dominant in the “milk-phospholipid” group.

Interestingly, while the overall number of microbial species (a measure of “diversity”) didn’t show wild swings, the balance among species shifted a signal that early-life diet can gently “nudge” which microbes take hold. Because these microbes help digest nutrients and shape metabolism, these early shifts may influence how babies process fats and grow, possibly affecting body fat, energy use, and even lifelong metabolic health. Indeed, by one year, infants on the milk-droplet formula tended to have body-mass measures closer to those breast-fed, compared with traditional formula hinting at long-term effects of those early microbial changes.

In short: what babies drink early in life doesn’t just feed their bodies, it feeds their microbial community. And the type of fat in that first diet can steer which microbes become permanent residents in the gut. That early microbial “sculpting” might matter more than we thought for how a child grows, digests food, and sets up metabolism for years to come.

Multi-omics data integration of biosample collected at 3 months of life. The fecal microbiota, fecal metabolomic, and plasma metabolomic profiles measured at 3 months were integrated using DIABLO. Good classification performance was obtained (classification error rate = 0.20), and it was possible to observe that infants from the Reference group were clustering apart from the Test and Control groups. Circos plot highlighted correlation (r > 0.6) between variables from the different omics blocks. Enterococcaceae and Enterococcus, which were most abundant in Control infants, negatively correlated with plasma triglycerides (TG) and fecal ceramides (Cer), while Bacteroida, Bacteroidales, Bacteroidaceae, and Bacteroides, which were most abundant in Reference infants, negatively correlated with several fecal hexosylceramides (HexCer) and Cer and plasma phosphatidylcholines (PC). FA, fatty acids; Hex2 Cer, dihexosylceramides; lysoPC, lysophosphatidylcholines; SM, sphingomyelins.

How Feeding Your Gut Smartly Can Support Metabolic Health

What we eat doesn’t just fuel us, it also feeds the trillions of microbes living in our gut, and that relationship can shape our health in unexpected ways. A recent study explored how a specific dietary intervention affected gut microbes in people at risk for metabolic troubles. Over time, the researchers found the meal plan nudged the balance of gut bacteria toward a “friendlier” community even without extreme diet changes.

Among the microbes that responded were familiar “good” bacteria: fiber-loving species such as Eubacterium rectale and Roseburia faecis increased noticeably under the new diet. Meanwhile, some species often linked to less-healthy guts including certain members of the genera Ruminococcus and Bacteroides became less abundant. Despite these shifts, the overall number of bacterial species and the “diversity” of the gut microbiome remained fairly stable, indicating the change was more about who lived in the gut than how many.

Why does this matter? These beneficial microbes are known to break down fiber and plant-based foods into compounds that support healthy metabolism and lower inflammation. The study also found matching shifts in gut and blood metabolites of small molecules produced or modified by microbes which correlated with improvements in blood-sugar and cholesterol levels. In other words, the gut’s microbial rebalancing wasn’t just a curious side-effect; it likely helped drive better metabolic health.

In short: by giving our gut microbes the “right food,” we may tilt them toward species that support long-term health. It suggests that sometimes, metabolic improvements come not just from eating less but from eating smarter.

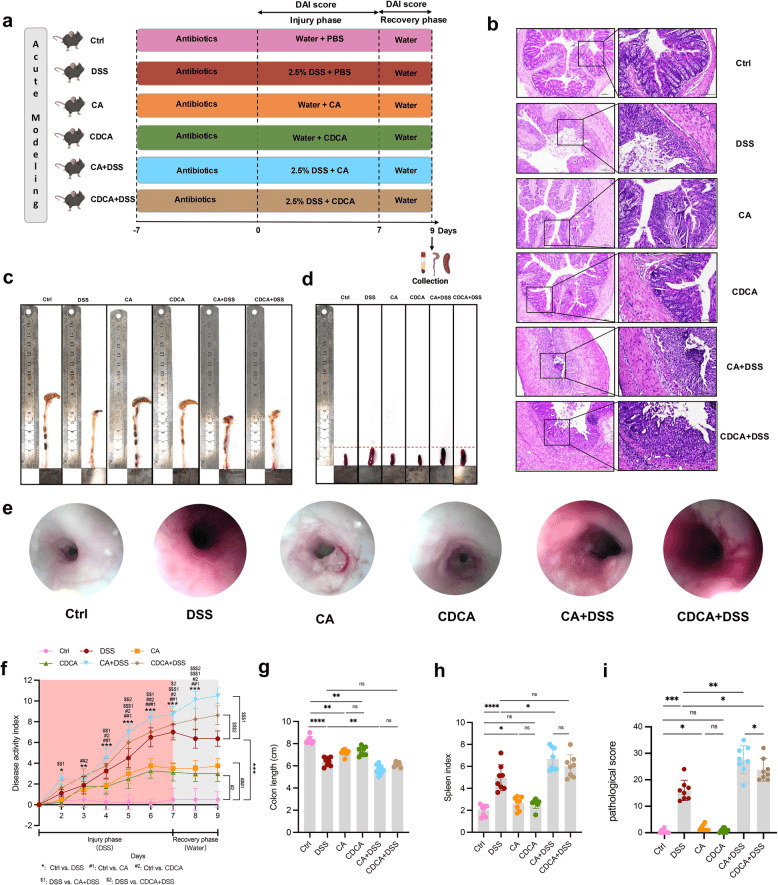

Primary BA administration in acute modeling mice. a Flow chart. b Representative H&E images, c Representative colon images, d Representative spleen images, e Representative endoscopic images of the colon, f DAI score, g Colon length, h Spleen index, i Pathological score of acute modeling mice. ns p > 0.05; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

Targeting the Gut–Liver Axis: How Probiotics Support Chemotherapy Tolerance in Lung Cancer

Chemotherapy targets cancer, but it often affects much more than tumors including the gut microbes and liver, two systems that quietly influence how the body tolerates treatment. This study explored how adding oral nutrition supplements combined with specific probiotics impacted the microbiome of lung cancer patients and whether those improvements translated into better liver function at the core of the gut–liver axis.

The patients who received both nutritional support and probiotics experienced a notable rise in beneficial gut bacteria, particularly Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, microbes known for maintaining gut lining integrity, reducing inflammation, and producing helpful fatty acids that communicate with the liver. At the same time, levels of opportunistic or inflammatory-linked bacteria, including Enterobacter and other Gram-negative species, declined, a shift that signals a more balanced, supportive gut ecosystem.

These microbial changes had meaningful effects: patients showed lower inflammatory markers and improved liver enzyme profiles, suggesting less stress on the liver during chemotherapy. The gut didn’t just improve in isolation the microbial rebalancing appeared to send healthier chemical messages through the bloodstream to the liver, easing its workload and supporting detoxification pathways.

This study highlights a powerful message: by nourishing patients’ bodies and their bacteria, we may support not just digestion, but how well the liver and immune system cope with cancer treatment. The gut–liver axis isn’t just a scientific term it may become a valuable ally in helping patients stay stronger during therapy.