Holobiome: Research I Articles I Updates I News I Series I Feed

Holobiome is a blog series that offers an AI-assisted summary of the latest research articles on human microbiome.

Gut Health and Overeating: The Microbiome Connection Explained

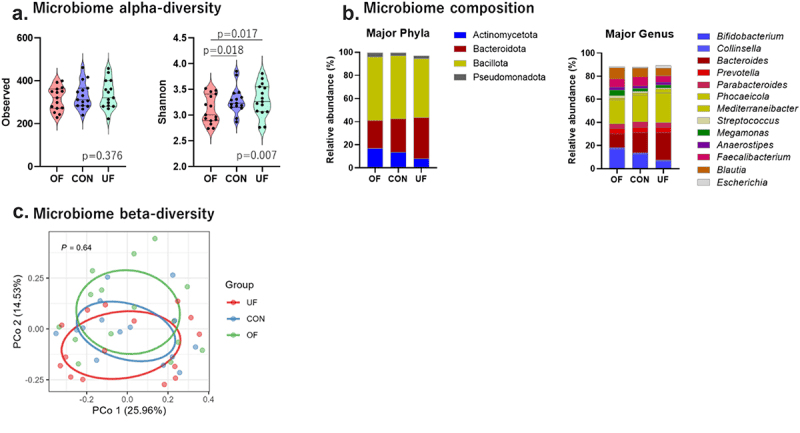

What you eat doesn’t just affect your weight or energy, it also changes the community of microbes living inside your gut, and this can influence how your body handles food. In a small study, healthy volunteers had their diets adjusted: for a short time they ate more than usual, sometimes less, or at normal amounts. The researchers then looked at how those changes affected the gut microbiome, energy absorption, and even levels of serotonin in their poop.

One of the most intriguing findings: when people overrate, the abundance of a key bacterial group Bacteroides shifts, and levels of a bacterial enzyme called tryptophanase go down. That enzyme helps certain gut bacteria produce molecules from dietary tryptophan, which in turn influence serotonin (yes the same chemical linked to mood) in the gut. With overfeeding, the team saw lower fecal serotonin compared with normal or under-feeding conditions.

These observations hint at something powerful: the balance and activity of gut microbes may shift quickly based on how much we eat, and that can affect not just digestion and energy use but also the chemical signals in our gut. A drop in serotonin in the gut, linked to changes in bacterial species and enzyme activity, suggests overeating might subtly alter how the gut and brain communicate. That could influence mood, digestion speed, and overall gut comfort.

In everyday life, this means our diet isn’t just fuel it’s a major force shaping the invisible ecosystem inside us. Eating patterns that fluctuate widely could disrupt microbial balance and affect how we digest food or how our gut signals to the rest of the body. It adds another reason to aim for balanced eating not just for calories or nutrients, but to support a healthy, well-behaved microbiome.

Changes in the diversity and composition of the intestinal microbiota due to dietary intervention. Major phyla and genera of the microbiome composition indicate the dominant bacteria with an average bacterial composition ≥1.0% of the relative abundance.

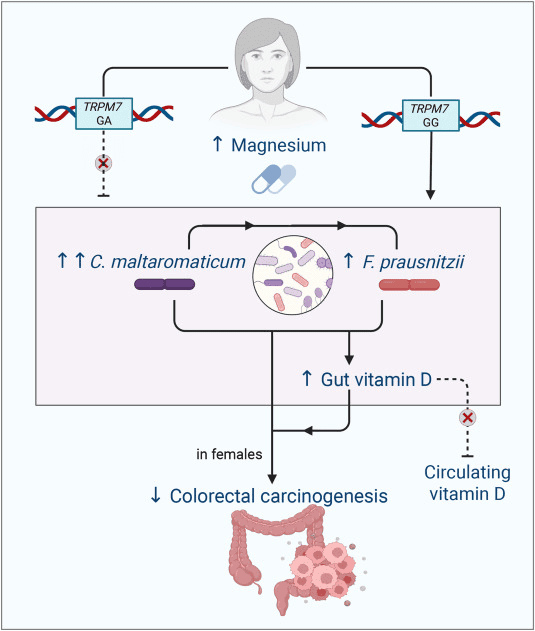

How Magnesium Trains Your Gut Microbes to Make Vitamin D

Most of us think of vitamin D as something we get from sunshine or supplements, but this study adds a twist: certain gut microbes may be able to make vitamin D right inside the colon and magnesium seems to help them flourish. The researchers focused on two key bacteria, Carnobacterium maltaromaticum and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. In earlier mouse work, this duo teamed up to turn vitamin D precursors into active vitamin D in the gut and helped protect against colorectal cancer. Here, the team tested whether giving people personalized magnesium supplements could gently “nudge” these microbes in a helpful direction.

Over 12 weeks, adults at risk for colorectal polyps were randomly given either magnesium or a placebo. The scientists then measured these bacteria in stool, rectal swabs, and tiny mucosal biopsies. In people whose magnesium-handling gene (TRPM7) worked normally, magnesium noticeably boosted C. maltaromaticum and, to a lesser extent, F. prausnitzii especially in rectal swab samples and particularly in women. In contrast, people carrying a specific TRPM7 variant sometimes showed the opposite pattern, with magnesium lowering levels of these microbes in certain gut niches.

What does this mean for health? While the study didn’t prove that these microbial shifts directly raised blood vitamin D, it supports the idea that magnesium can reshape the gut ecosystem in ways that may influence local vitamin D production right at the lining of the colon, where cancer begins. Exploratory analyses hinted that higher C. maltaromaticum might be linked to fewer serrated polyps, while F. prausnitzii in the gut wall could be a double-edged sword in some contexts. Overall, the work points toward a future where “precision magnesium” could be used to cultivate vitamin-D-producing microbes and fine-tune colorectal cancer prevention, especially in those whose genes and microbiome are poised to benefit.

Mechanistic figure: magnesium supplementation increases levels of C. maltaromaticum and F. prausnitzii. TRPM7, transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M, member 7

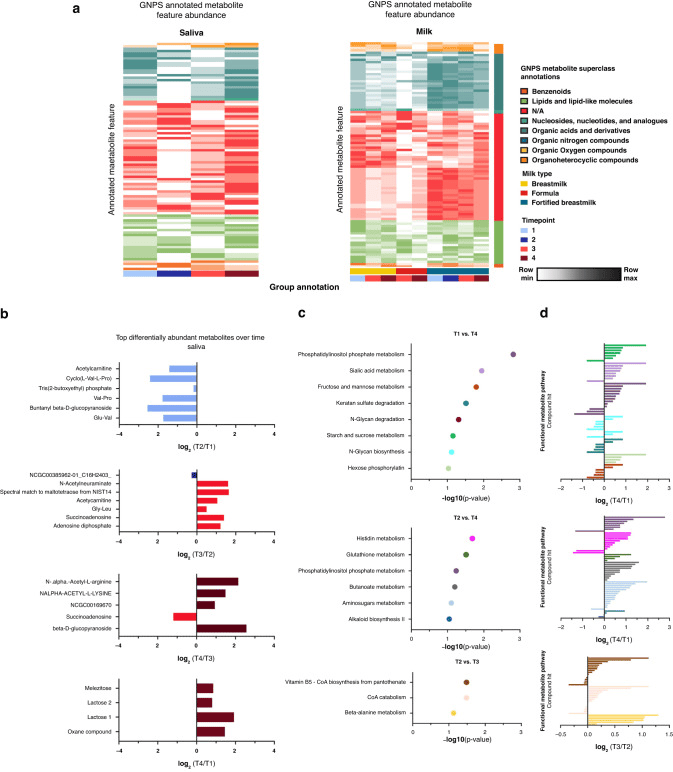

From Breast Milk to Bacteria: The Science of Early Microbiome Building

We tend to think of breast milk as nourishment for newborns but it’s also a living cocktail that helps shape a baby’s earliest microbiome. In the recent pilot study of preterm infants, researchers tracked how the microbes in babies’ guts and mouths evolved over the first few months of life, comparing those who were breastfed with those given other feeding alternatives.

What they saw was that the microbial community in the infants changed gradually over time. As weeks passed, some bacterial groups grew, others receded, reflecting a typical “settling in” of the baby’s internal microbial ecosystem. At the same time, the chemical by-products and metabolites in their gut also shifted, hinting that the microbes weren’t just present, they were actively working: digesting, fermenting, and likely helping the infant adapt to life outside the womb.

This matters because the first few months are a critical window: the gut microbiome helps train a baby’s immune system, supports digestion, and lays the foundations for long-term health. By showing that feeding, especially breast milk, influences which microbes take root and how metabolically active they become, this study reinforces the idea that early nutrition does more than feed a baby’s body; it helps build a healthy inner ecosystem.

In simpler words: those first feeds may shape more than weight and growth; they may help build a thriving, balanced microbiome that supports digestion, immunity, and possibly long-term well-being. For preterm infants especially, guiding the microbiome gently through proper feeding could be a powerful, natural way to help them start life on stronger footing.

a) Heatmap of GNPS annotated metabolite features in saliva and milk samples colored by metabolite (row) min to max milk-type across time points. Metabolite average intensity by time point was used for visualization. Column grouping was done by time point and milk type in saliva and milk samples respectively. b) Bar plots showing differently abundant GNPS annotated metabolites in saliva samples based on timepoint binary comparisons. Significantly altered metabolites are colored by time points in which they are found to be higher in each respective binary comparison. c) MetaboAnalyst functional pathway analysis across time points for saliva samples. Samples were sorted by p value of the respective binary comparisons for pathway analysis. d) MetaboAnalyst functional pathway compound hits with their respective log2-fold change per comparison. Bars are colored by pathway hits.

When a Heart Attack Reaches the Gut: How Microbes Respond

A recent pilot study followed people who had a sudden heart attack (technically an Acute Coronary Syndrome, or ACS) and tracked what happened to their gut microbes over the next month compared with people who had a more stable, chronic heart condition. What they found was surprising: even after just a few weeks, the community of bacteria in the gut shifts noticeably after a heart event.

Specifically, certain bacteria known for producing beneficial short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) especially a group called Butyricicoccus and its relatives in the family Butyricoccaceae became more abundant in the guts of people recovering from ACS. This was not seen in the stable-heart (chronic) group. In tandem, researchers observed a rise in butanoic acid (a type of SCFA) in the blood, which suggests these gut microbes might be getting more active fermenting fibre and producing useful by-products.

Why this matters: SCFAs like butanoic acid are known to support gut integrity, calm inflammation, and even influence overall metabolism so having more SCFA-producing bacteria might be part of the body’s way of healing and rebalancing after the stress of a heart event. In other words, a heart attack doesn’t just hurt the heart it appears to tweak your gut ecosystem too, possibly with protective effects in the recovery phase.

If the findings hold up in larger studies, this could open a new window for recovery: using diet or other gut-targeted strategies to encourage those helpful SCFA-makers, perhaps supporting better long-term cardiovascular and gut health.

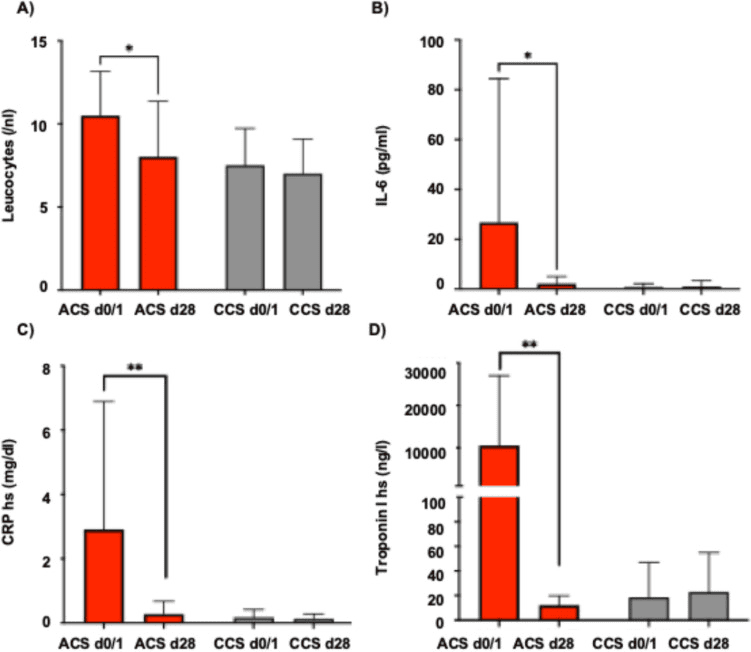

Inflammatory panel (A-C) including A leucocytes, B interleukin-6 and C high-sensitive CRP and D hs-Troponin I levels in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) compared to patients with chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) at baseline and follow-up at 28 days. Statistical significance was calculated using the student’s t-test (* denotes p < 0,05, ** denotes p < 0.01)

How Caffeine Supports a Healthier Scalp From the Microbial Level Up

Most of us know caffeine as a wake-up for the brain, but this study shows it may also be a wake-up call for the tiny life forms living on our scalp. Researchers tested a shampoo containing caffeine and adenosine in people with hair loss and looked at how their scalp microbes changed over 12 weeks, alongside improvements in hair density and shedding.

On the bacterial side, the “problem-leaning” groups Pseudomonas and Escherichia-Shigella went down, while Cutibacterium, a familiar skin resident often linked to a healthier, more balanced scalp environment, went up after using the active shampoo. At the same time, the fungal landscape shifted: Malassezia, the yeast frequently tied to dandruff and irritated scalps, decreased, while Talaromyces, a less commonly discussed genus, increased.

These changes weren’t just cosmetic in a narrow sense. The team also saw that certain scalp lipids (fats) moved in step with specific microbes: for example, lipid shifts were strongly linked to Escherichia-Shigella and Talaromyces levels. Because scalp oils help feed or restrain different microbes, this tight coupling suggests caffeine and adenosine may be nudging both the oil mix and the microbes together into a more hair-friendly balance.

Put simply, the shampoo didn’t just wash the scalp, it helped “re-landscape” its ecosystem. By dialing down bacteria and yeasts associated with irritation and cranking up those linked to a calmer, healthier scalp, caffeine and adenosine may support anti-hair-loss effects through the microbiome as well as through direct action on hair follicles. It’s early, and the study was small, but it points to a future where treating hair loss also means caring for the scalp’s invisible residents.

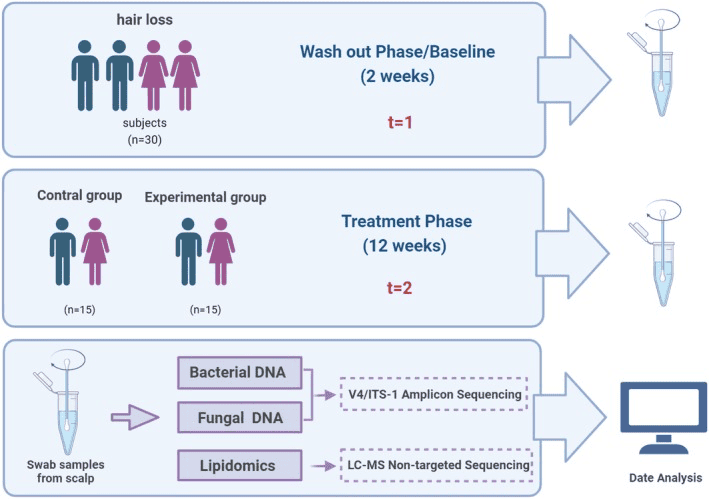

Overview of the study design. Swab samples were collected from scalps at baseline (t = 1) and treatment (t = 2) phases. Bacterial and fungal DNA was extracted from the collected swab samples, and amplicon (bacterial 16S rDNA V4 and fungal ITS1 region) and lipidomic analyses were used to carry out taxonomic and functional analyses.